Though Auguste Comte coined the term "sociology," the first book with the term sociology in its title was written in the mid-19th century by the English philosopher Herbert Spencer. Following Comte, Spencer created a synthetic philosophy that attempted to find a set of rules to explain everything in the universe, including social behavior.

Spencer's Synthetic Philosophy

Like Comte, Spencer saw in sociology the potential to unify the sciences, or to develop what he called a "synthetic philosophy. " He believed that the natural laws discovered by natural scientists were not limited to natural phenomena; these laws revealed an underlying order to the universe that could explain natural and social phenomena alike. According to Spencer's synthetic philosophy, the laws of nature applied to the organic realm as much as to the inorganic, and to the human mind as much as to the rest of creation. Even in his writings on ethics, he held that it was possible to discover laws of morality that had the same authority as laws of nature. This assumption led Spencer, like Comte, to adopt positivism as an approach to sociological investigation; the scientific method was best suited to uncover the laws he believed explained social life.

Spencer and Progress

But Spencer went beyond Comte, claiming that not only the scientific method, but scientific knowledge itself was universal. He believed that all natural laws could be reduced to one fundamental law, the law of evolution. Spencer posited that all structures in the universe developed from a simple, undifferentiated homogeneity to a complex, differentiated heterogeneity, while being accompanied by a process of greater integration of the differentiated parts. This evolutionary process could be found at work, Spencer believed, throughout the cosmos. It was a universal law, applying to the stars and the galaxies as much as to biological organisms, and to human social organization as much as to the human mind. Thus, Spencer's synthetic philosophy aimed to show that natural laws led inexorably to progress. He claimed all things—the physical world, the biological realm, and human society—underwent progressive development.

In a sense, Spencer's belief in progressive development echoed Comte's own theory of the three-stage development of society. However, writing after important developments in the field of biology, Spencer rejected the ideological assumptions of Comte's three-stage model and attempted to reformulate the theory of social progress in terms of evolutionary biology. Following this evolutionary logic, Spencer conceptualized society as a "social organism" that evolved from a simpler state to a more complex one, according to the universal law of evolution. This social evolution, he argued, exemplifed the universal evolutionary process from simple, undifferentiated homogeneity to complex, differentiated heterogeneity.

As he elaborated the theory, he proposed two types of society: militant and industrial. Militant society, structured around relationships of hierarchy and obedience, was simple and undifferentiated. Industrial society, based on voluntary behavior and contractually assumed social obligations, was complex and differentiated. Spencer questioned whether the evolution of society would result in peaceful anarchism (as he had first believed) or whether it pointed to a continued role for the state, albeit one reduced to minimal functions—the enforcement of contracts and external defense. Spenser believed, as society evolved, the hierarchical and authoritarian institutions of militant society would become obsolete.

Social Darwinism

Spencer is perhaps best known for coining the term "survival of the fittest," later commonly termed "social Darwinism." But, popular belief to the contrary, Spencer did not merely appropriate and generalize Darwin's work on natural selection; Spencer only grudgingly incorporated Darwin's theory of natural selection into his preexisting synthetic philosophical system. Spencer's evolutionary ideas were based more directly on the evolutionary theory of Lamarck, who posited that organs are developed or diminished by use or disuse and that the resulting changes may be transmitted to future generations. Spencer believed that this evolutionary mechanism was necessary to explain 'higher' evolution, especially the social development of humanity. Moreover, in contrast to Darwin, Spencer held that evolution had a direction and an endpoint—the attainment of a final state of equilibrium. Evolution meant progress, improvement, and eventually perfection of the social organism.

Criticism

Though Spencer is rightly credited with making a significant contribution to early sociology, his attempt to introduce evolutionary ideas into the realm of social science was ultimately unsuccessful. It was considered by many to be actively dangerous. Critics of Spencer's positivist synthetic philosophy argued that the social sciences were essentially different from the natural sciences and that the methods of the natural sciences—the search for universal laws was inappropriate for the study of human society.

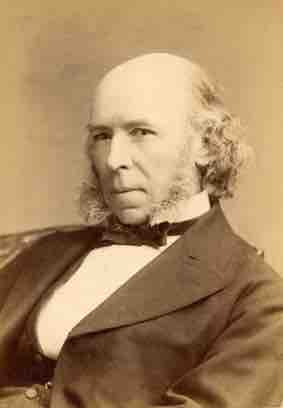

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer built on Darwin's framework of evolution, extrapolating it to the spheres of ethics and society. This is why Spencer's theories are often called "social Darwinism."