As part of his theory of the development of societies in, The Division of Labour in Society (1893), sociologist Emile Durkheim characterized two categories of societal solidarity: organic and mechanical.

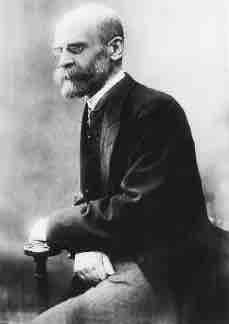

Émile Durkheim

Durkheim formally established the academic discipline and, with Karl Marx and Max Weber, is commonly cited as the principal architect of modern social science and father of sociology.

Mechanical and Organic Solidarity

In a society exhibiting mechanical solidarity, its cohesion and integration comes from the homogeneity of individuals. People feel connected through similar work, educational and religious training, and lifestyle. Mechanical solidarity normally operates in "traditional" and small-scale societies, and it is usually based on kinship ties of familial networks.

Organic solidarity is social cohesion based upon the dependence individuals have on each other in more advanced societies. It comes from the interdependence that arises from specialization of work and the complementarities between people—a development that occurs in "modern" and "industrial" societies. Although individuals perform different tasks and often have different values and interest, the order and very solidarity of society depends on their reliance on each other to perform their specified tasks. "Organic" refers to the interdependence of the component parts. Thus, social solidarity is maintained in more complex societies through the interdependence of its component parts (e.g., farmers produce the food to feed the factory workers who produce the tractors that allow the farmer to produce the food). As a simple example, farmers produce food to feed factory workers who produce tractors that, in the end, allow the farmer to produce more food.

The two types of solidarity can be distinguished by formal and demographic features, type of norms in existence, and the intensity and content of the conscience collective.