Temporal motivation theory (TMT) is an integrative motivational theory developed by Piers Steel and Cornelius J. Konig. The theory emphasizes time as a critical motivational factor and focuses on the impact of deadlines on the allocation of attention to particular tasks. TMT argues that as a deadline for completing an activity nears, the perceived usefulness or benefit of that activity increases exponentially. TMT is particularly useful for understanding human behaviors like procrastination and goal setting.

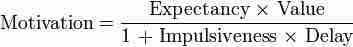

TMT states that an individual's motivation for a task can be derived from the following formula (in its simplest form):

Temporal Motivation

Temporal motivation theory argues that motivation is heavily influenced by time.

In this equation, motivation is the desire for a particular outcome. Expectancy, or self-efficacy, is the likelihood of success; value is the reward associated with the outcome; impulsiveness is the individual's ability to withstand urges; and delay is the amount of time until the realization of the outcome (i.e., the deadline). The greater the individual's expectancy for successfully completing the task, and the higher the value of the outcome associated with it, the higher the individual's motivation will be. In contrast, both impulsivity and a greater amount of time before a deadline tend to reduce motivation.

Examples of Temporal Motivation Theory

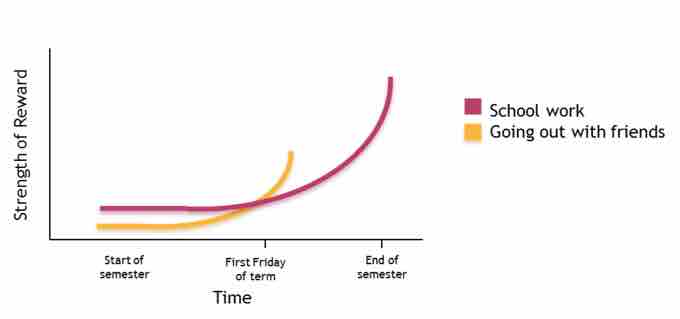

Consider a student who is given one month to study for a final exam. Throughout the month, the student has two options: studying or socializing. The student enjoys socializing but needs to achieve a good grade. At the beginning of the student's study period (where there is a long delay before the deadline), the reward of studying is not immediate (and therefore has low value); therefore, the motivation to study is lower than the motivation to socialize. However, as the study period diminishes from several weeks to several days, the motivation to study will surpass the motivation to socialize.

Motivation over time

This graph illustrates how a student's motivation tends to change over time: early in the semester he may be more motivated to socialize with friends; later in the semester, school work takes precedence.

Suppose the student really doesn't understand the material and doesn't feel confident that he will be able to grasp it in time for the exam (low self-efficacy, or expectancy). In addition, the student just got a new video game that he has been dying to play (high value) and has a hard time resisting the urge to play (high impulsiveness). With the exam still a month away (long delay), the student's motivation to study is likely to be low, and he will play the video game instead. As the exam date approaches (shorter delay), his motivation to study may increase, leading him to put the video game away.