Hunger is the set of physical and psychological sensations that arise when food is needed by the body. It appears to increase activity and movement in many animals; this response may increase an animal's chances of finding food. Food consumption (particularly overconsumption) can result in weight gain, whereas insufficient consumption, or malnutrition, will cause significant weight and motivational energy loss. Hunger is controlled by the hypothalamus and hormones. It is regulated over both the long term and the short term.

Hormones

The physical sensation of hunger comes from contractions of the stomach muscles. These contractions are believed to be triggered by high concentrations of the hormone ghrelin. Two other hormones, peptide YY and leptin, cause the physical sensations of being full. Ghrelin is released if blood sugar levels get low, a condition that can result from going long periods without eating.

Hypothalamus

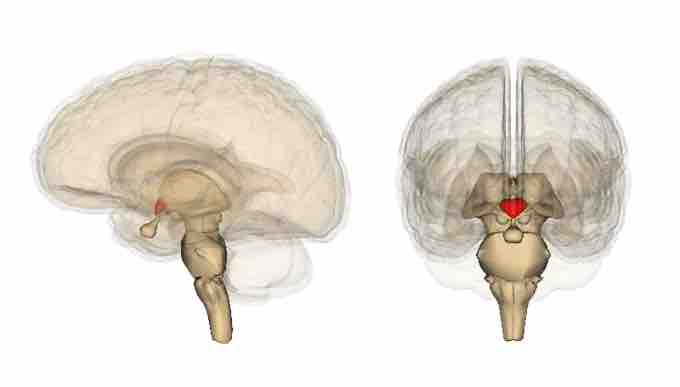

The hypothalamus regulates the body's physiological homeostasis. When you are dehydrated, freezing, or exhausted, the appropriate biological responses are activated automatically: body fat reserves are utilized, urine production is inhibited, and blood is shunted away from the surface of the body. The drive to eat, or drink water, or seek warmth is activated.

In the 1940s, the "dual-center" model, which divided the hypothalamus into hunger (lateral hypothalamus) and satiety (ventromedial hypothalamus) centers, was popular. This theory developed from the findings that bilateral lesions of the lateral hypothalamus can cause anorexia, a severely diminished appetite for food, while bilateral lesions on the ventromedial hypothalamus can cause overeating and obesity. Recently, further study has called the dual-center model into question, but the hypothalamus certainly does play a role in hunger.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is the region of the forebrain below the thalamus that forms the basal portion of the diencephalon. It regulates body temperature and some metabolic processes, and governs the autonomic nervous system.

Long-Term Hunger Regulation

The long-term regulation of hunger prevents energy shortfalls and is concerned with the regulation of body fat. Leptin, a hormone secreted exclusively by adipose cells in response to an increase in body-fat mass, helps regulate long-term hunger and food intake. Leptin serves as the brain's indicator of the body's total energy stores. The function of leptin is to suppress the release of neuropeptide Y (NPY), which in turn prevents the release of appetite-enhancing orexins from the lateral hypothalamus. This decreases appetite and food intake, promoting weight loss. Though rising blood levels of leptin do promote weight loss to some extent, its main role is to protect the body against weight loss in times of nutritional deprivation.

Short-Term Hunger Regulation

The short-term regulation of hunger deals with appetite and satiety. It involves neural signals from the GI tract, blood levels of nutrients, and GI-tract hormones.

Neural Signals from the GI Tract

The brain can evaluate the contents of the gut through vagal nerve fibers that carry signals between the brain and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Studies have shown that the brain can sense differences between macronutrients through these vagal nerve fibers. Stretch receptors (mechanoreceptors that respond to an organ being stretched or distended) work to inhibit appetite when the GI tract becomes distended. They send signals along the vagus nerve afferent pathway and ultimately inhibit the hunger centers of the hypothalamus.

Nutrient Signals

Blood levels of glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids provide a constant flow of information to the brain that may be linked to regulating hunger and energy intake. Nutrient signals indicate fullness. They inhibit hunger by raising blood glucose levels, elevating blood levels of amino acids, and affecting blood concentrations of fatty acids.

Hormonal Signals

Hormones can have a wide range of effects on hunger. The hormones insulin and cholecystokinin (CCK) are released from the GI tract during food absorption and act to suppress feelings of hunger. However, during fasting, glucagon and epinephrin levels rise and stimulate hunger. When blood sugar levels fall, the hypothalamus is stimulated. Ghrelin, a hormone produced by the stomach, triggers the release of orexin from the hypothalamus, signaling to the body that it is hungry.

Starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy, nutrient, and vitamin intake. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. Prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and, untreated, leads to death. Individuals experiencing starvation lose substantial fat and muscle mass, called catabolysis, when the body breaks down its own fat and muscle for energy. Vitamin deficiency, diarrhea, skin rashes, edema, and heart failure are also common results of starvation. In a state of starvation, other motivators—such as the desire for sleep, sex, and social activities— decrease. Individuals suffering from starvation may experience irritability, lethargy, impulsivity, hyperactivity, and more apathy over time.