Chief Legislator

The president has many official and unofficial roles. The formal powers and duties of the president are outlined in Article II of the Constitution. As chief legislator, the president shapes policy. The Constitution is reticent about the president's role in legislating, yet the relationship between Congress and the executive is the most important aspect of the U.S. system of government. The president can gather information from the bureaucracy, present a legislative agenda to Congress, and go to the American public for support for his legislative agenda.

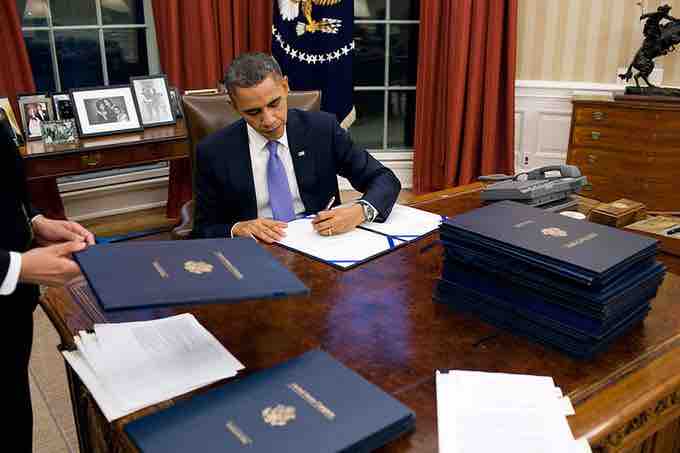

President Barack Obama Signing Legislation

President Barack Obama signs legislation in the Oval Office, Dec. 22, 2010. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

The president may suggest and request that Congress enact laws he believes are needed. He can attempt to influence Congress through promises of patronage and favors. He stays in touch with Congress formally through written messages and informally through private meetings, parties, and phone calls. When the president receives legislation, he decides whether to veto it, use the pocket veto, sign it, or do nothing. If the president does nothing, then if Congress is still in session ten days later it becomes law.

In 1996, Congress attempted to enhance the president's veto power with the Line Item Veto Act. The legislation empowered the president to sign any spending bill into law while simultaneously striking certain spending items within the bill, particularly any new spending, any amount of discretionary spending, or any new limited tax benefit. Once a president had stricken the item, Congress could pass that particular item again. If the president then vetoed the new legislation, Congress could override the veto by the ordinary method of a two-thirds vote in both houses. In Clinton v. City of New York (1998), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled such a legislative alteration of the veto power to be unconstitutional.