Conducting Polls

Generally, in order to conduct a poll, the survey methodologist must do the following :

Questionnaire

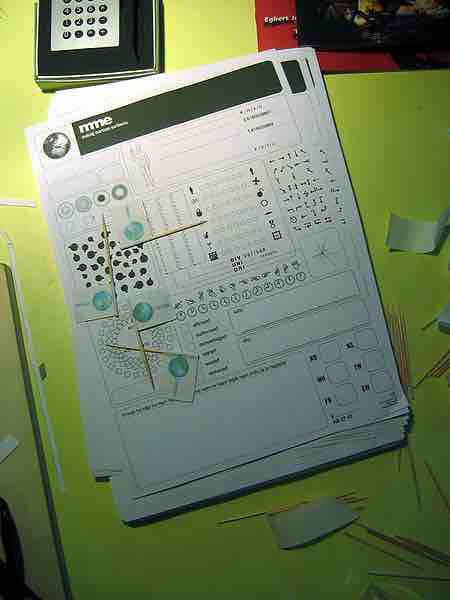

This is an example of a questionnaire.

- Identify and select potential sample members

- Contact sampled individuals and collect data from those who are difficult to reach

- Evaluate and test questions

- Select the mode for posing questions and collecting responses

- Train and supervise interviewers

- Check data files for accuracy and internal consistency

- Adjust survey estimates to correct for identified errors

Survey samples can be broadly divided into two types: probability samples and non-probability samples. Stratified sampling is a method of probability sampling such that sub-populations within an overall population are identified and included in the sample.

Usually, a poll consists of a number of questions that the respondent answers in a set format. A distinction is made between open-ended and closed-ended questions. An open-ended question asks the respondent to formulate his or her own answer; a closed-ended question asks the respondent to pick an answer from a given number of options. The response options for a closed-ended question should be exhaustive and mutually exclusive. Four types of response scales for closed-ended questions are as follows:

- Dichotomous: the respondent has two options

- Nominal-polytomous: the respondent has more than two unordered options

- Ordinal-polytomous: the respondent has more than two ordered options

- (bounded) Continuous: the respondent is presented with a continuous scale

A respondent's answer to an open-ended question can be coded into a response scale or analyzed using more qualitative methods.

A questionnaire is a series of questions asked to individuals to obtain statistically useful information about a given topic. When properly constructed and responsibly administered, questionnaires become a vital instrument for polling a population.

Adequate questionnaire construction is critical to the success of a poll. Inappropriate questions, incorrect ordering of questions, incorrect scaling, or bad questionnaire format can make the survey valueless, as it may not accurately reflect the views and opinions of the participants. Pretesting among a smaller subset of target respondents is useful method of checking a questionnaire and making sure it accurately captures the intended information.

Questionnaire construction issues

The topics should fit the respondents' frame of reference. Their background may affect their interpretation of the questions. Respondents should have enough information or expertise to answer the questions truthfully.

The type of scale, index, or typology to be used is determined. The level of measurement used determines what can be concluded from the data. If the response option is yes/no then you will only know how many, or what percent, of your sample answered yes/no. You cannot, however, conclude what the average respondent answered.

The types of questions (closed, multiple-choice, open) should fit the statistical data analysis techniques available and the goals of the poll. Questions and prepared responses should be unbiased and neutral as to intended outcome. The order or "natural" grouping of questions is often relevant. Prior previous questions may bias later questions. Also, the wording should be kept simple: no technical or specialized vocabulary. The meaning should be clear. Ambiguous words, equivocal sentence structures and negatives may cause misunderstanding, possibly invalidating questionnaire results. Care should be taken to ask one question at a time. The list of possible responses should be collectively exhaustive. Respondents should not find themselves without category that fits them. Additionally, possible responses should be mutually exclusive; categories should not overlap. Writing style should be conversational, concise, accurate and appropriate to the target audience. "Loaded" questions evoke emotional responses and may skew results.

Many respondents will not answer personal or intimate questions. For this reason, questions about age, income, marital status, etc., are generally placed at the end of the survey. Thus, if the respondent refuses to answer these questions, the research questions will have already been answered.

Presentation of the questions on the page (or computer screen) and the use of graphics may affect a respondent's interest or distract from the questions.

Finally, questionnaires can be administered by research staff, by volunteers or self-administered by the respondents. Clear, detailed instructions are needed in either case, matching the needs of each audience.

Question sequence

Some further considerations about questionnaires are the following.

Questions should flow logically from one to the next, from the more general to the more specific, from the least sensitive to the most sensitive, from factual and behavioral questions to attitudinal and opinion questions, from unaided to aided questions.

Finally, according to the three stage theory, or the sandwich theory, initial questions should be screening and rapport questions. The second stage should concern the product specific questions. In the last stage demographic questions are asked.