In 1953, following a lawsuit that included a congressional resolution that authorized a governmental committee to investigate "all lobbying activities intended to influence, encourage, promote, or retard legislation," the Supreme Court narrowly construed "lobbying activities" to mean only "direct" lobbying. The Court defined this "direct" method of lobbying as "representations made directly to the Congress, its members, or its committees". It contrasted this with indirect lobbying, which it defined as efforts to influence Congress indirectly by trying to change public opinion.

Mobilizing Public Opinion

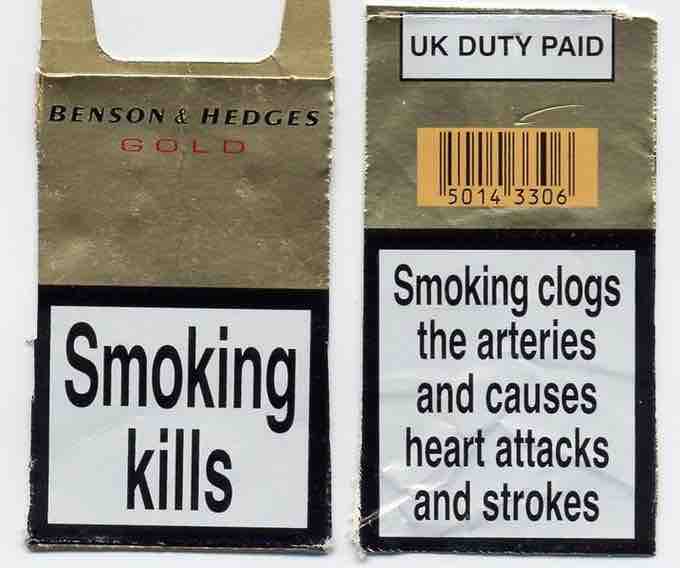

Large health notices on tobacco products is one way in which the anti-smoking lobby and the government have tried to mobilize public opinion against smoking.

Increasingly, lobbyists seek to influence politics by putting together coalitions and by utilizing outside lobbying to mobilize public opinion on issues. Larger, more diverse, and more wealthy coalitions tend to be more effective at outside lobbying (the "strength in numbers" principle often applies). These groups have been defined as "sustainable coalitions of similarly situated individual organizations in pursuit of like-minded goals. " According to one study, it is often difficult for a lobbyist to influence a staff member in Congress directly, because staffers tend to be well-informed, and because they frequently hear views from competing interests. As an indirect tactic, lobbyists often try to manipulate public opinion which, in turn, can sometimes exert pressure on congresspersons, who must frequently appeal to that public during electoral campaigns. One method for exerting this indirect pressure is the use of mass media. Interest groups often cultivate contacts with reporters and editors and encourage these individuals to write editorials and cover stories that will influence public opinion regarding a particular issue. Because of the important connection between public opinion and voting, this may have the secondary effect of influencing Congress. According to analyst Ken Kollman, it is easier to sway public opinion than a congressional staff member, because it is possible to bombard the public with "half-truths, distortion, scare tactics, and misinformation. " Kollman suggests there should be two goals in these types of efforts. First, communicate to policy makers that there is public support behind a particular issue, and secondly, increase public support for that issue among constituents. Kollman asserted that this type of outside lobbying is a "powerful tool" for interest group leaders. In a sense, using these criteria, one could consider James Madison as having engaged in outside lobbying. After the Constitution was proposed, Madison wrote many of the 85 newspaper editorials that argued for people to support the Constitution. These writings later came to be known as the Federalist Papers. As a result of Madison's "lobbying" effort, the Constitution was ratified, although there were narrow margins of victory in four of the states.

Lobbying today generally requires mounting a coordinated campaign, which can include targeted blitzes of telephone calls, letters, and emails to congressional lawmakers. It can also involve more public demonstrations, such as marches down the Washington Mall, or topical bus caravans. These are often put together by lobbyists who coordinate a variety of interest group leaders to unite behind a hopefully simple, easy-to-grasp, and persuasive message.