The modern federal apparatus owes its origins to changes that occurred during the period between 1861 and 1933. While banks had long been incorporated and regulated by the states, the National Bank Acts of 1863 and 1864 saw Congress establish a network of national banks that had their reserve requirements set by officials in Washington. During World War I, a system of federal banks devoted to aiding farmers was established, and a network of federal banks designed to promote home ownership came into existence in the last year of Herbert Hoover's administration. Congress used its power over interstate commerce to regulate the rates of interstate (and eventually intrastate) railroads and even regulate their stock issues and labor relations, going so far as to enact a law regulating pay rates for railroad workers on the eve of World War I. During the 1920s, Congress enacted laws bestowing collective bargaining rights on employees of interstate railroads and some observers dared to predict it would eventually bestow collective bargaining rights on workers in all industries. Congress also used the commerce power to enact morals legislation, such as the Mann Act of 1907 barring the transfer of women across state lines for immoral purposes, even as the commerce power remained limited to interstate transportation—it did not extend to what were viewed as intrastate activities such as manufacturing and mining.

As early as 1913, there was talk of regulating stock exchanges, and the Capital Issues Committee formed to control access to credit during World War I recommended federal regulation of all stock issues and exchanges shortly before it ceased operating in 1921. With the Morrill Land-Grant Acts Congress used land sale revenues to make grants to the states for colleges during the Civil War on the theory that land sale revenues could be devoted to subjects beyond those listed in Article I Section 8 of the Constitution. On several occasions during the 1880s, one house of Congress or the other passed bills providing land sale revenues to the states for the purpose of aiding primary schools. During the first years of twentieth century, the endeavors funded with federal grants multiplied, and Congress began using general revenues to fund them—thus utilizing the general welfare clasues's broad spending power, even though it had been discredited for almost a century (Hamilton's view that a broad spending power could be derived from the clause had been all but abandoned by 1840).

During Herbert Hoover's administration, grants went to the states for the purpose of funding poor relief. The Supreme Court began applying the Bill of Rights to the states during the 1920s even though the Fourteenth Amendment had not been represented as subjecting the states to its provisions during the debates that preceded ratification of it. The 1920s also saw Washington expand its role in domestic law enforcement. Disaster relief for areas affected by floods or crop failures dated from 1874, and these appropriations began to multiply during the administration of Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921). By 1933, the precedents necessary for the federal government to exercise broad regulatory power over all economic activity and spend for any purpose it saw fit were almost all in place. Virtually all that remained was for the will to be mustered in Congress and for the Supreme Court to acquiesce.

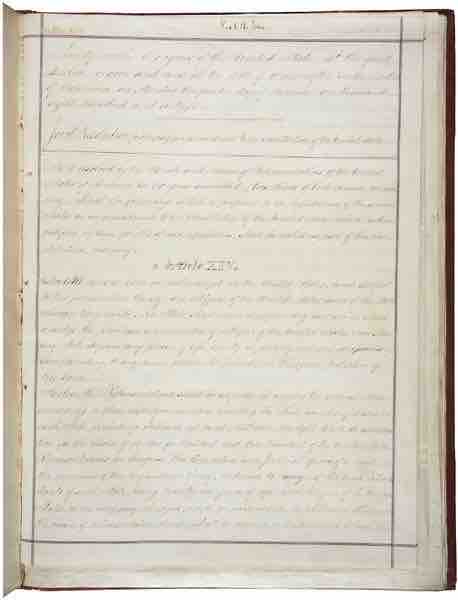

Page One of the 14th Amendment

The Supreme Court began applying the Bill of Rights to the states during the 1920s even though the Fourteenth Amendment had not been represented as subjecting the states to its provisions during the debates that preceded ratification of it.