The larynx (plural: larynges), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the neck of humans and most animals that is involved in breathing, sound production, coughing, and protecting the trachea against food aspiration during eating.

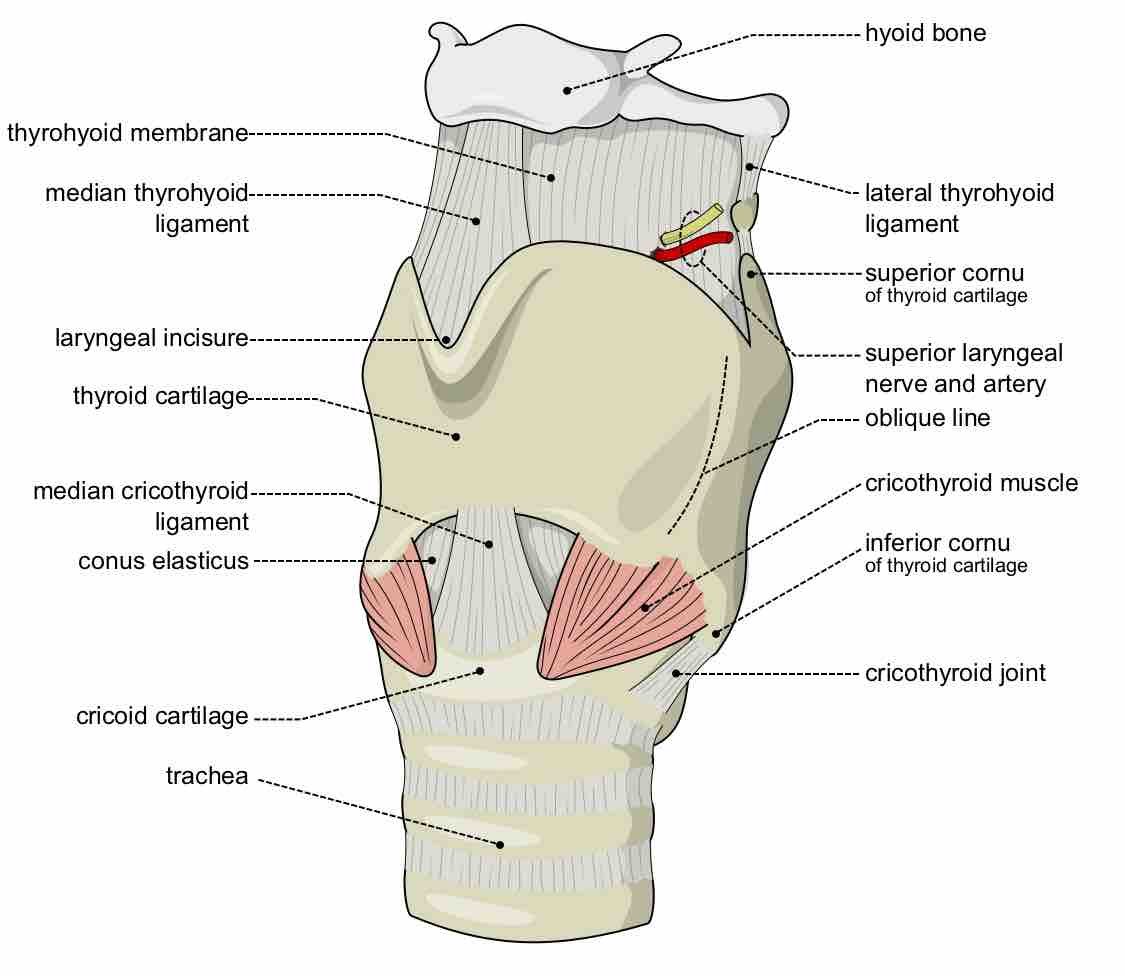

External view of the larynx

This figure is a detailed view of the external aspect of the larynx.

Anatomy of the Larynx

In adult humans, the larynx is found in the anterior neck at the level of the C3–C6 vertebrae in the backbone. It connects the inferior part of the pharynx (laryngopharynx) with the trachea. The laryngeal skeleton consists of three single cartilages (thyroid, epiglottic, and cricoid).

- The thyroid cartilage is particularly notable for forming the Adam's apple, the visible bulge made by the larynx when looking at the throat, and protects the larynx from injury.

- The epiglottic cartilage is the body of the epiglottis itself that connects to the larynx from above.

- The cricoid cartilage connects the larynx to the trachea from below.

There are also three sets of cartilages that are paired on either side of the larynx (arytenoid, corniculate, and cuneiform) that allow the position of the larynx to move during voice production.

The larynx connects to the hyoid bone (the bone that forms the floor of the mouth) from above. The larynx extends vertically from the tip of the epiglottis to the border of the cricoid cartilage that marks the formal beginning of the trachea.

The interior of the larynx consists of three regions, the supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis. The glottis is the midsection that contains the vocal folds (folds of muscular epithelium), while the supraglottis and subglottis are the areas of the larynx that are above and below the glottis respectively. In newborn infants, the larynx is initially at the level of the C2–C3 vertebrae, but descends as the child grows.

The glottis consists of two pairs of mucosal folds. These folds are false vocal folds (vestibular folds) and true vocal folds (folds). The false vocal folds are covered by respiratory epithelium, while the true vocal folds are covered by stratified squamous epithelium.

The false vocal folds are not responsible for sound production, but rather for resonance. These false vocal folds do not contain muscle, while the true vocal folds do have skeletal muscle. The two sets of folds are separated by the vocal ligament, with the false vocal folds above, and the true vocal cords below the ligament. The true vocal folds are often referred to as the vocal cords, however the folds technically aren't cords.

Physiology of the Larynx

The most notable and unique function of the larynx is phonation (voice production). The vocal folds of the larynx have two positions, open and closed. During breathing the folds remain open, but they close during swallowing or phonation.

When air from the lungs passes through closed folds during exhalation, the folds vibrate and create sound. The pitch produced depends on the length and tightness of the vocal folds.

The vagus nerves innervate the larynx and signal the muscles and paired cartilage (the arytenoid) of the larynx to work together to open and close the vocal folds as well as change their length and tension to alter pitch. Longer vocal folds have a lower pitch, which is part of the reason why men have deeper voices compared to women, because their larger larynxes have longer vocal folds.

Besides phonation, there are a few other important functions of the larynx. The folds of the larynx close and move upwards during swallowing, which causes the epiglottis to close off the trachea. This helps prevent aspiration of food into the lungs or choking from a blockage of food in the trachea.

The larynx closes off during coughing to help prevent harmful gasses from entering the lungs. During a cough reflex, air is forced out of the lungs, which can remove accumulated mucus, fluid, or blood from the lungs during injury, infection, or cancer of the lungs, as well as food or objects in the trachea during choking.

Finally, the larynx can be signaled to open its folds wider than usual to increase the flow of air into and out of the lungs during heavy breathing when the body requires more oxygen.