Deep wounds that damage the dermis, or even the underlying muscle and fat, are more difficult to heal than shallow, epidermal-only wounds. The wound healing processes may be extended and scar tissue is likely to form due to improper re-epithelialization.

Additionally, deep wounds are more susceptible to infection, and also to the development of systemic infection through the circulatory system, as well as dysregulation that results in chronic wounds such as ulcers.

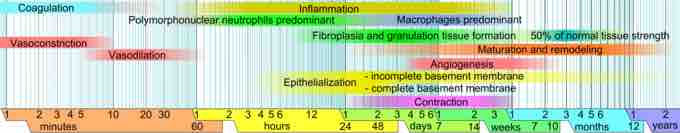

Wound healing phases

This image illustrates the phases of wound healing. Limits vary within faded intervals, mainly by wound size and healing conditions, but the image does not include major impairments that cause chronic wounds.

The wound healing process for deep wounds is similar to that of shallow wounds. However, with the removal of the dermis and its associated skin appendages, re-epithelialization can only occur from the wound edge, with no contribution from the dermal compartment.

Therefore, proper reconstitution of the epidermis is often only seen at the edge of the wound, with fibrous scar tissue—formed from the extracellular matrix (ECM) deposited during the proliferative phase—covering the rest of the wound site.

With the formation of a scar, the original physiological properties of the tissue are lost. For example scars are less flexible than skin, and do not feature sweat glands or hair follicles.

The ECM formed during wound healing may also be weaker in deep wounds, making the site susceptible to additional later wounding. The provisional ECM laid down during the proliferative phase is rich in fibronectin and collagen III that combine to allow quicker cell movement through the wound, which is very important during wound healing.

However, the ECM of mature skin is rich in collagen I. In large, deep wounds the remodelling of a fibronectin and collagen III-rich ECM to a collagen-I rich ECM may not occur, leading to a weakening of the tissue.