The intestinal phase is the stage of digestion in which the duodenum responds to arriving chyme and moderates gastric activity through hormones and nervous reflexes. The duodenum initially enhances gastric secretion, but soon inhibits it. Stretching of the duodenum accentuates vagal reflexes that stimulate the stomach, and peptides and amino acids in the chyme stimulate G cells of the duodenum to secrete more gastrin, which further stimulates the stomach. Soon, however, the acid and semi-digested fats in the duodenum trigger the enterogastric reflex. That is, the duodenum sends inhibitory signals to the stomach by way of the enteric nervous system, while also sending signals to the medulla that inhibit the vagal nuclei. This reduces vagal stimulation of the stomach and stimulates sympathetic neurons, which send inhibitory signals to the stomach.

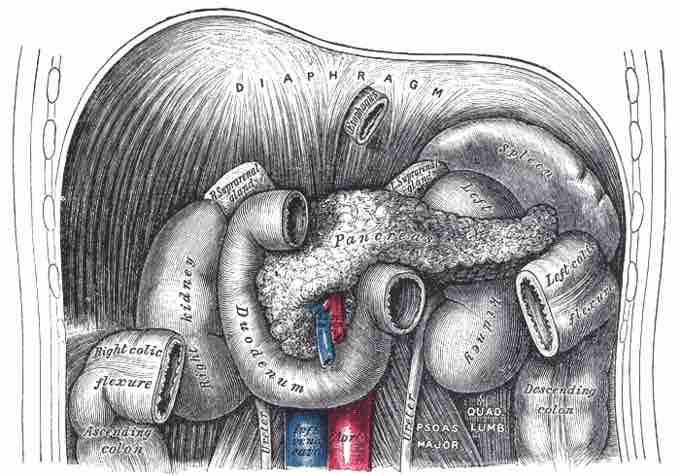

Duodenum

The intestinal phase of digestion occurs in the duodenum, the first segment of the small intestine.

Chyme also stimulates duodenal enteroendocrine cells to release secretin and cholecystokinin. These hormones primarily stimulate the pancreas and gall bladder, but they also suppress gastric secretion and motility. The effect of this is that gastrin secretion declines and the pyloric sphincter contracts tightly to limit the admission of more chyme into the duodenum. This gives the duodenum time to work on the chyme it has already received before being loaded with more. The enteroendocrine cells also secrete glucose dependent insulinotropic peptide. Originally called gastric-inhibitory peptide, it is no longer thought to have a significant effect on the stomach. Rather, it is probably more concerned with stimulating insulin secretion in preparation for processing the nutrients about to be absorbed by the small intestine.