The human body uses a variety of mental and physiological cues to initiate the process of digestion. Throughout our gastrointestinal (GI) tract, each organ serves a specific purpose to bring our food from the plate to a digestible substance, from which nutrients can be extracted.

THE DIGESTIVE TUBE

Our digestive system is like a long tube, with different segments doing different jobs. The major organs within our digestive system can be split up into two major segments of this tube: the upper gastrointestinal tract, and the lower gastrointestinal tract.

The upper gastrointestinal, or GI, tract is made up of three main parts: the esophagus, the stomach, and the small intestine. The lower GI tract contains the remainder of the system: the large intestine, rectum, and anus. The exact dividing line between "upper" and "lower" tracts can vary, depending on which medical specialist is examining the GI tract.

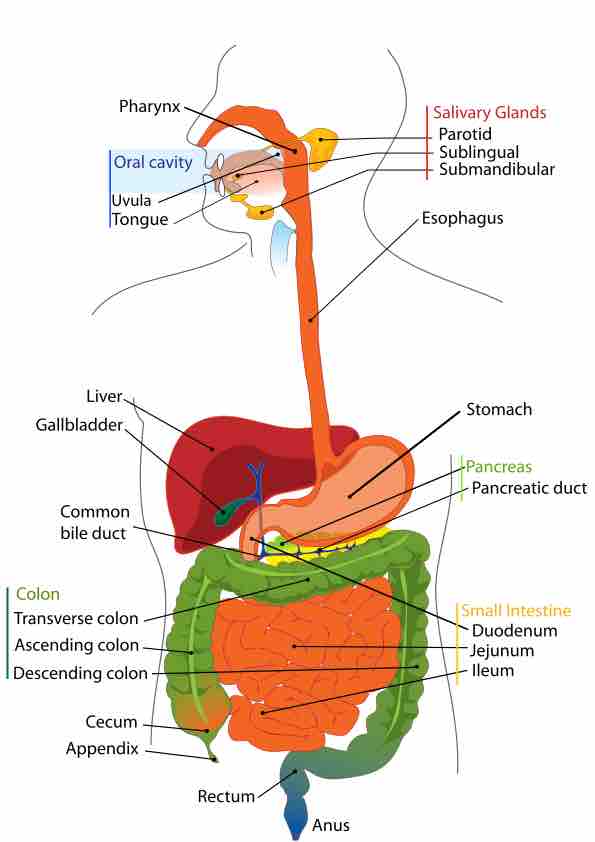

The organs of the gastrointestinal tract

This diagram shows the relationship between the various organs of the digestive system.

FOOD BREAKDOWN AND ABSORPTION: THE UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

When we take a bite of food, the food material gets chewed up and processed in the mouth, where saliva begins the process of chemical and mechanical breakdown. The chewing process here is also known as mastication. When we mix up food with saliva, the resulting mushy wad is called a bolus. The bolus gets swallowed, and there begins its journey through the upper gastrointestinal tract.

THE ESOPHAGUS

The upper GI tract begins with the esophagus, the long muscular tube that carries food to the stomach. The throat cavity in which our esophagus originates is known as the pharynx. As we swallow, the bolus moves down our esophagus, from pharynx to stomach, through waves of muscle movement known as peristalsis. Next the bolus reaches the stomach itself.

THE STOMACH

The stomach is a muscular, hollow bag, and it’s an important part of the upper GI tract. Many organisms have a variety of stomach types, with many segments or even multiple stomachs. As humans, we have only one stomach.

Here our bolus gets mixed with digestive acids, furthering breakdown, and turning the bolus material into a slimy mess called chyme. The chyme moves on into the small intestine, where nutrients are absorbed.

THE SMALL INTESTINE

The small intestine is an impressive digestive tube, spanning an average of 20 feet in length. The twists and turns of the small intestine, along with tiny interior projections known as villi, help to increase surface area for nutrient absorption.

This snaking tube is made up of three parts, in order from the stomach: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. As the chyme makes its way through each segment of the small intestine, pancreatic juices from the pancreas start to break down proteins. Soapy bile from the liver, stored in the gallbladder, gets squirted into the small intestine to help emulsify - or break apart - fats. Now thoroughly digested, with nutrients absorbed along the path of the small intestine, what remains of our food gets passed into the lower GI tract.

Waste Compaction and Removal: The Lower Gastrointestinal Tract

THE LARGE INTESTINE (COLON)

Following nutrient absorption, the food waste reaches the large intestine, or colon. The large intestine is responsible for compacting waste material, removing water, and producing feces - our solid waste product. Accessory organs like the cecum and appendix, which are remnants of our evolutionary past, serve as special pockets at the beginning of the large intestine. The compacted and dried-out waste passes to the rectum, and out of the body through the anus. Healthy gut bacteria in the large intestine also help metabolize our waste as it finishes its journey.