Platelets, also called thrombocytes, are membrane-bound cell fragments derived from the fragmentation of larger precursor cells called megakaryocytes, which are derived from stem cells in the bone marrow. Platelets are important for the blood clotting process, making them essential for wound healing.

Platelet Structure and Distribution

Platelets are irregularly shaped, have no nucleus, and typically measure only 2–3 micrometers in diameter. Platelets are not true cells, but are instead classified as cell fragments produced by megakaryocytes. Because they lack a nucleus, they do not contain nuclear DNA. However, they do contain mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA, as well as endoplasmic reticulum fragments and granules from the megakaryocyte parent cells. Platelets also contain adhesive proteins that allow them to adhere to fibrin mesh and the vascular endothelium, as well as to a microtubule and microfilament skeleton that extends into filaments during platelet activation. Less than 1% of whole blood consists of platelets. They are about 1/10th to 1/20th as abundant as white blood cells.

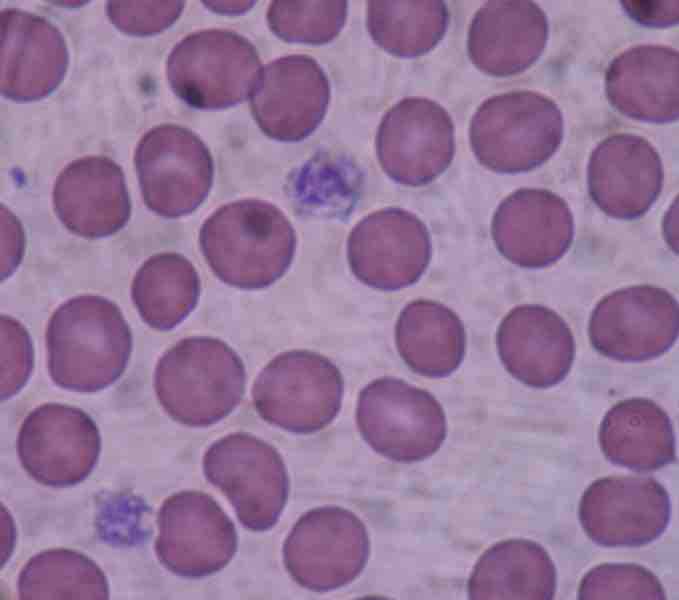

Platelet

Image from a light microscope (40×) from a peripheral blood smear surrounded by red blood cells. One platelet can be seen in the upper left side of the image (purple) and is significantly smaller in size than the red blood cells (stained pink) and the two large neutrophils (stained purple).

Platelet Functions

Platelets circulate in blood plasma and are primarily involved in hemostasis (stopping the flow of blood during injury), by causing the formation of blood clots, also known as coagulation. The adhesive surface proteins of platelets allow them to accumulate on the fibrin mesh at an injury site to form a platelet plug that clots the blood. The complex process of wound repair can only begin once the clot has stopped bleeding.

Platelets secrete many factors involved in coagulation and wound healing. During coagulation, they release factors that increase local platelet aggregation (thromboxane A), mediate inflammation (serotonin), and promote blood coagulation through increasing thrombin and fibrin (thromboplastin). They also release wound healing-associated growth factors including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which directs cell movement; TGF beta, which stimulates the deposition of extracellular matrix tissue into a wound during healing; and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulates angiogenesis, or the regrowth of blood vessels. These growth factors play a significant role in the repair and regeneration of connective tissues. Local application of these platelet-produced healing-associated factors in increased concentrations has been used as an adjunct to wound healing for several decades.

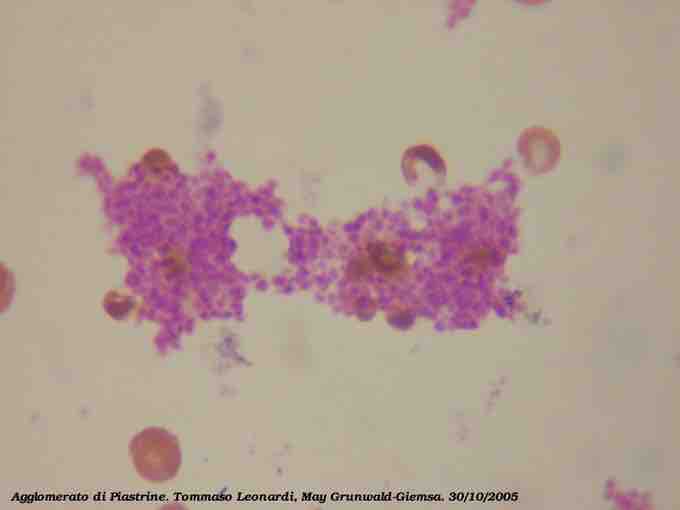

Platelets

A blood slide of platelets aggregating, or, clumping together. The platelets are the small, bright purple fragments.

If the number of platelets is too low, excessive bleeding can occur and wound healing will be impaired. However, if the number of platelets is too high, blood clots can form (thrombosis), which may obstruct blood vessels and result in ischemic tissue damage caused by a stroke, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, or the blockage of blood vessels to other parts of the body. Thrombosis also occurs when blood is allowed to pool, which causes clotting factors and platelets to form a blood clot even in the absence of an injury.