Osteogenesis

Early in gestation, a fetus has a cartilaginous skeleton from which the long bones and most other bones gradually form throughout the remaining gestation period and for years after birth in a process called endochondral ossification. Ossification (or osteogenesis) is the process of laying down new bone material by cells called osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes resulting in the formation of normal, healthy bone tissue. Intramembranous ossification is the direct laying down of bone into the primitive connective tissue (mesenchyme). This is how the flat bones of the skull and the clavicles are formed. Endochondral ossification involves cartilage as a precursor. Ossification of the mandible occurs in the fibrous membrane covering the outer surfaces of Meckel's cartilages.

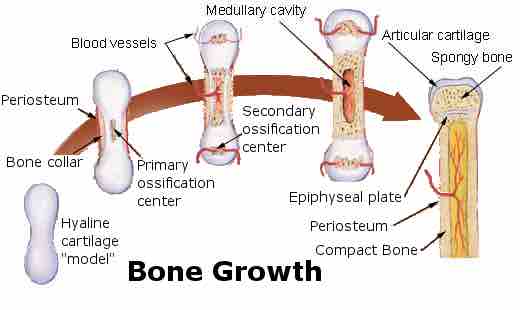

Endochondral Ossification

The development of the primary and secondary ossification centers

Intramembranous Ossification

In the case of bones which are developed in membrane, no cartilaginous mold precedes the appearance of the bony tissue. The membrane that occupies the place of the future bone resembles connective tissue, and ultimately forms the periosteum; it is composed of fibers and granular cells in a matrix. The peripheral portion is more fibrous, while, in the interior the cells or osteoblasts predominate. The whole tissue is richly supplied with blood vessels. As the osteogenetic fibers grow out to the periphery they continue to calcify, and give rise to fresh bone spicules. Therefore, a network of bone is formed, the meshes of which contain the blood vessels and a delicate connective tissue crowded with osteoblasts. The bony trabeculæ thicken by the addition of fresh layers of bone formed by the osteoblasts on their surface, and the meshes are correspondingly encroached upon. Subsequently successive layers of bony tissue are deposited under the periosteum and around the larger vascular channels that become the Haversian canals, so that the bone increases much in thickness.

Endochondral Ossification

The perichondrium becomes the periosteum that contains a layer of undifferentiated cells (osteoprogenitor cells) which later become osteoblasts. These osteoblasts secrete osteoid against the shaft of the cartilage model (Appositional Growth). This serves as support for the new bone. Chondrocytes in the primary center of ossification begin to grow (hypertrophy). They stop secreting collagen and other proteoglycans and begin secreting alkaline phosphatase, an enzyme essential for mineral deposition. Then calcification of the matrix occurs and the hypertrophic chondrocytes begin to die. This creates cavities within the bone. The hypertrophic chondrocytes (before apoptosis) secrete Vascular Endothelial Cell Growth Factor that induces the sprouting of blood vessels from the perichondrium. Blood vessels forming the periosteal bud invade the cavity left by the chondrocytes and branch in opposite directions along the length of the shaft. The blood vessels carry hemopoietic cells, osteoprogenitor cells and other cells inside the cavity. The hemopoietic cells will later form the bone marrow. Osteoblasts, differentiated from the osteoprogenitor cells that entered the cavity via the periosteal bud, use the calcified matrix as a scaffold and begin to secrete osteoid, which forms the bone trabecula. Osteoclasts, formed from macrophages, break down spongy bone to form the medullary (bone marrow) cavity.