In mammals, breathing (inhaling) occurs during the contraction and flattening of the diaphragm—a domed muscle separating the thorax and abdomen. If the abdomen is relaxed then its volume is increased; the fall in pressure in the thorax is met by the entry of air. When the diaphragm relaxes air leaves largely by elasticity of the lung. This is a quiet, relaxed breathing state, requiring little energy. When requirements increase, the abdominal muscles resist expansion. Increased abdominal pressure then tilts the diaphragm and ribcage upwards, increasing volume and air entry.

Expiration follows relaxation of diaphragm and abdominal muscles, but can be increased by the downward action of abdominal muscles on the rib cage. This forced expiration increases pressure across walls of airways, and may lead to narrowing or even perhaps to wheezing. Intercostal muscles (which are auxiliary) stiffen and shape the rib cage. Speech depends on the balance between the two forms of breathing. In humans, conscious change often modifies autonomous reaction to need, a pattern that can vary due to things like fear or anxiety, loss of lung elasticity (due to aging), pulmonary diseases such as emphysema , or abdominal expansion from obesity.

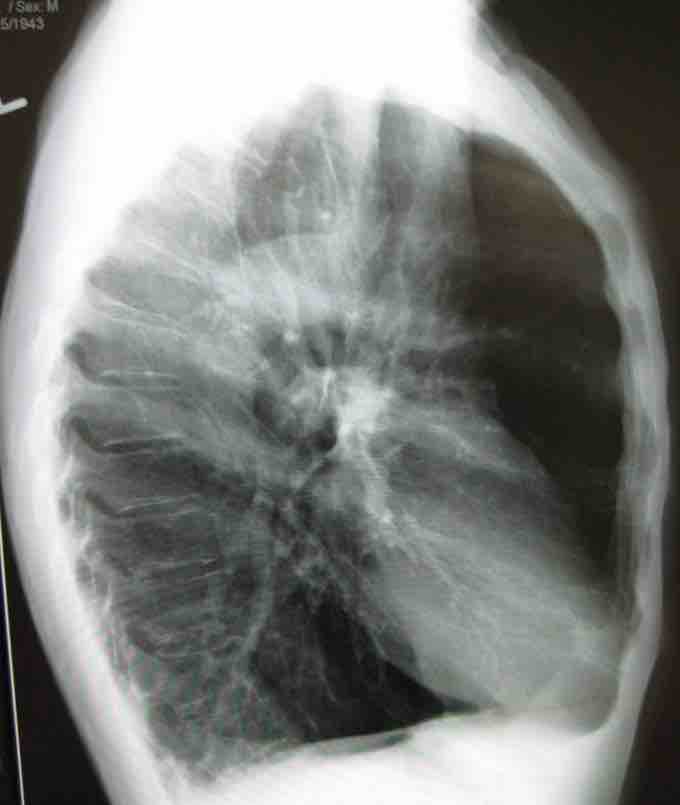

Lateral chest X-ray of a patient with emphysema

Emphysema is a common lung disease in the elderly. Note the barrel-shaped chest and flat diaphragm.

Some types of emphysema occur as a normal part of aging, and are commonly found in the elderly (85 years of age and older). At about 20 years of age, humans stop developing new alveolar tissue . In the years following this cessation, lung tissue begins to deteriorate (on a "net" basis), albeit at a relatively slow rate. As alveoli die, the number of lung capillaries decreases, and the elastin of the lungs begins to break down causing loss of pulmonary elasticity. This is a normal and natural part of aging in healthy people.

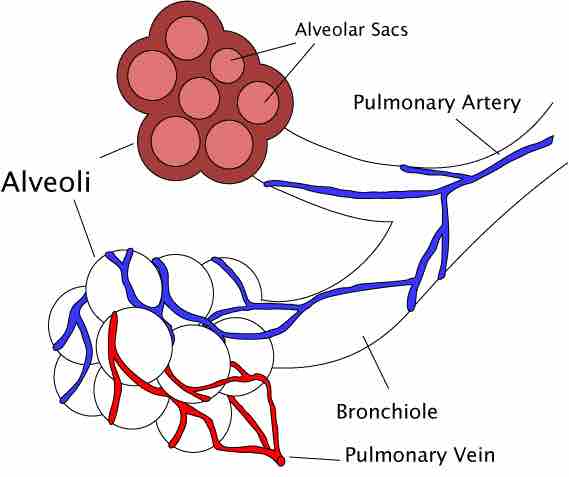

Diagram of an Alveoli

An alveoli with both cross-section and external views

Age also contributes to loss of strength and mass in the chest muscles—these weaken, bones and cartilage start to deteriorate, and posture changes. Together, such age-related changes in respiratory system structures can cause or contribute to the development of emphysema. Though not all elderly people will develop clinically evident emphysema, all are at risk of decreasing respiratory function, which limits maximum lung performance and causes discomfort at higher levels of exertion.