Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites and cannot grow on inanimate media. They need living cells for replication, which can be provided by inoculation in live animals among other methods used to culture viruses (cell culture or inoculation of embryonated eggs). Inoculation of human volunteers was the only known method of cultivation of viruses and understanding viral disease. In 1900, Reed and his colleagues used human volunteers for their work on yellow fever. Due to serious risk involved, human volunteers are recruited only when no other method is available and the virus is relatively harmless. Smallpox was likely the first disease people tried to prevent by purposely inoculating themselves with other infections and was the first disease for which a vaccine was produced. Today, studying viruses via the inoculation of humans would require a stringent study of ethical practices by an institutional review board.

Yellow fever virus

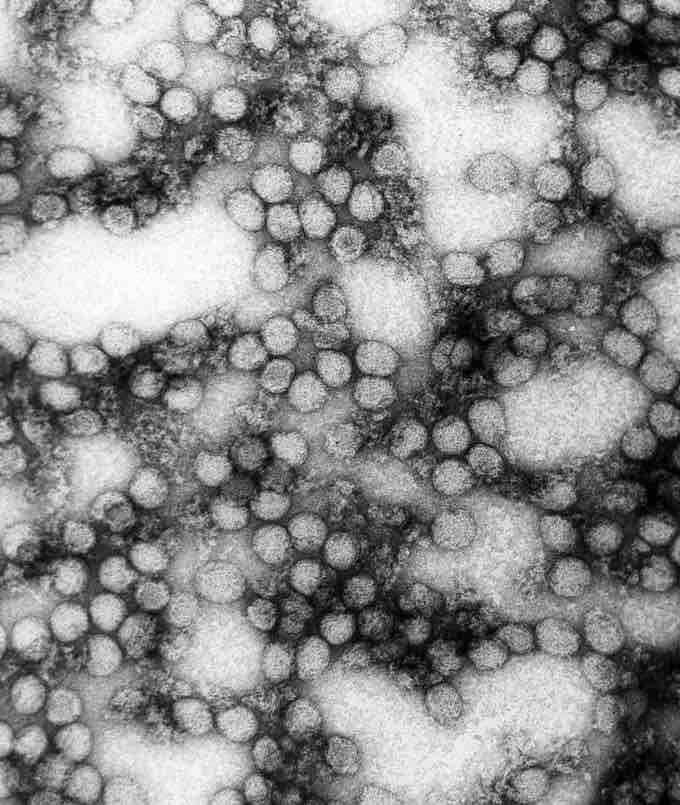

A micrograph of the yellow fever virus.

In the past few decades, animal inoculation has been employed for virus isolation. The laboratory animals used include monkeys, rabbits, guinea pigs, rats, hamsters, and mice. The choice of animals and route of inoculation (intracerebral, intraperitoneal, subcutaneous, intradermal, or intraocular) depends largely on the type of virus to be isolated. Handling of animals and inoculation into various routes requires special experience and training. In addition to virus isolation, animal inoculation can also be used to observe pathogenesis, immune response, epidemiology, and oncogenesis. Growth of the virus in inoculated animals may be indicated by visible lesions, disease, or death. Sometimes, serial passage into animals may be required to obtain visible evidence of viral growth. Animal inoculation has several disadvantages as immunity may interfere with viral growth, and the animal may harbor latent viruses.