Europa's Possible Ocean

Europa, discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei, is one of Jupiter's four moons (called the Galilean moons) . Europa is covered by a layer of water/ice. It is fascinating to note that although Europa maintains a constant temperature of around -145 degrees Celsius, the water on its surface is not completely frozen (referred to as liquid water).

Europa

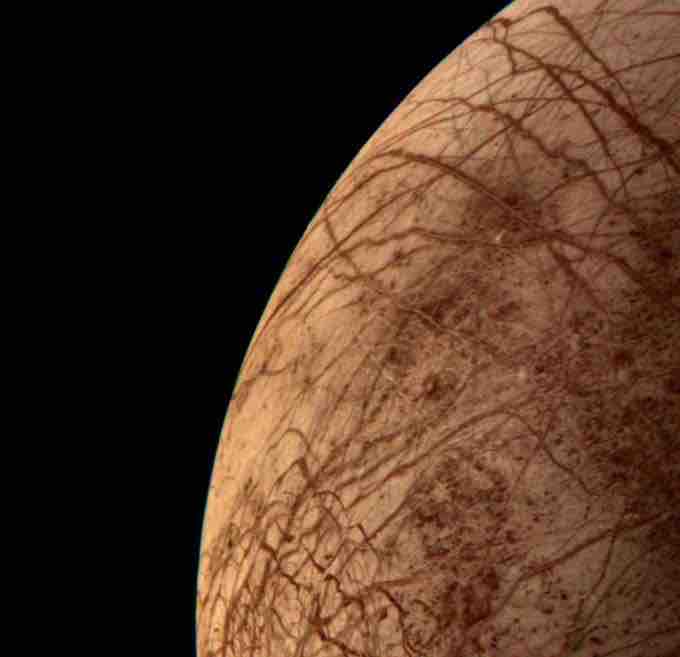

An image of the Jovian moon Europa was acquired by Voyager 2

Europa's Oceanic Properties

Europa has tidal heating that develops from friction due to its eccentric orbit around Jupiter. In other words, in a similar fashion to the tides flowing in and out on Earth due to the moon's gravitational pull, the tides on Europa are affected due to its orbit around Jupiter and possibly also its orbital resonance with other Galilean moons. The planet's gravitational pull is stronger on the near side than the far, creating tidal bulges that can crack the icy crust's surface and heat the interior. It has also been proposed that volcanoes deep under the moon's surface contain hydrothermal vents that heat and maintain the liquid water.

Evidence of an Ocean

Scientists propose the Europa's smooth surface, with very few craters, must be the result of ice covering an ocean which evens out the surface. Originally there were hypotheses that the atmosphere burning up or weathering of the craters were the source of Europa's smooth surface, but these ideas were discarded due to Europa's thin atmosphere. Additionally, some parts of the moon's surface shows blocks of ice that are separated but seem to fit together like a puzzle. These icebergs could have been shifted by slushy or liquid water beneath. Ridges in Europa's landscape suggest existent water seeping up the ice cracks, refreezing, and then forming higher and higher ridges.

Models of Europa's Surface

Geologists have analyzed images taken from the Voyager and Galileo expeditions and have come up with two possible models for the surface of this moon: the thick-ice model and the thin-ice model.

The thick-ice model refers to Europa's large craters and their surrounding concentric rings. These rings are filled with what appears to be flat, fresh ice. Due to these observations and assumptions, combined with the calculated amount of heat present on the moon's surface, the outer crust of solid ice would be about 6-19 miles thick and the liquid water underneath would be about 60 miles deep.

The thin-ice model, which is not widely supported by scientists, proposes that the icy crust would be only about 660 feet thick. Other scientists suggest that this layer is simply the outermost layer that changes constantly due to Europa's tides. Currently, there is little evidence to support this model.