Sometimes firms fail to cooperate with each other, even when cooperation would bring about a better collective outcome. The prisoner's dilemma is a canonical example of a game analyzed in game theory that shows why two individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interest to do so.

In the game, two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of speaking to or exchanging messages with the other. The police offer each prisoner a bargain :

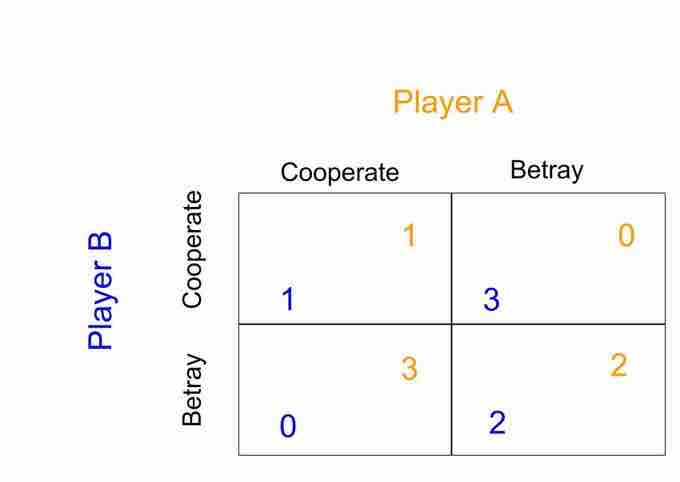

Prisoner's Dilmma

Betrayal in the dominant strategy for both players, as it provides for a better individual outcome regardless of what the other player does. However, the resulting outcome is not Pareto-optimal. Both players would clearly have been better off if they had cooperated.

- If Prisoner A and Prisoner B both confess to the crime, each of them will serve two years in prison.

- If A confesses but B denies the crime, A will be set free, while B will serve three years in prison (and vice versa).

- If both A and B deny the crime, both of them will only serve one year in prison.

For both players, the choice to betray the partner by confessing has strategic dominance in this situation; it is the better strategy for each player regardless of what the other player does. This set of strategies is thus a Nash equilibrium in the game--no player would be better off by changing his or her strategy. As a result, all purely self-interested prisoners would betray each other, resulting in a two year prison sentence for both. This outcome is not Pareto optimal; it is clearly possible to improve the outcomes for both players through cooperation. If both players had denied the crime, they would each be serving only one year in prison.

Similarly to the prisoner's dilemma scenario, cooperation is difficult to maintain in an oligopoly because cooperation is not in the best interest of the individual players. However, the collective outcome would be improved if firms cooperated, and were thus able to maintain low production, high prices, and monopoly profits.

One traditional example of game theory and the prisoner's dilemma in practice involves soft drinks. Coca-Cola and Pepsi compete in an oligopoly, and thus are highly competitive against one another (as they have limited other competitive threats). Considering the similarity of their products in the soft drink industry (i.e. varying types of soda), any price deviation on part of one competitor is seen as an act of non-conformity or betrayal of an established status quo.

In such a scenario, there are a number of plausible reactions and outcomes. If Coca-Cola reduces their prices, Pepsi may follow to ensure they do not lose market share. In this situation, defection results in a lose-lose. Which is to say that, due to the initial price reduction by Coca-Cola (betrayal of status quo), both companies likely see reduced profit margins. On the other hand, Pepsi could uphold the price point despite Coca-Cola's deviation, sacrificing market share to Coca-Cola but maintaining the established price point. Prisoner dilemma scenarios are difficult strategic choices, as any deviation from established competitive practice may result in less profits and/or market share.