Inflation is a persistent increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time. Specifically, the rate of inflation is the percent increase of prices from the start to the end of the given time period (usually measured annually).

When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services. Consequently, inflation reflects a reduction in the purchasing power per unit of money – a loss of real value in the medium of exchange and unit of account within the economy.

The decrease in purchasing power means that inflation is good for debtors and bad for creditors. Since debtors usually pay back loans in a nominal amount, they want to give up the least purchasing power possible. For example, if you borrowed money and have to pay back $100 next year, you'd like that $100 to be worth as little as possible. Conversely, creditors don't like inflation because the money they are getting paid is can purchase less than if there were no inflation.

What Causes Inflation?

When looking at individual goods, price changes may result from changes in consumer preferences, changes in the price of inputs, changes in the price of substitute or complement goods, or many other factors. When looking at the inflation rate for an entire economy, however, these microeconomic factors are relatively unimportant.

Instead, most economists agree that in the long run, inflation depends on the money supply. Specifically, the money supply has a direct, proportional relationship with the price level, so if, for example, the currency in circulation increased, there would be a proportional increase in the price of goods. To understand this, imagine that tomorrow, every single person's bank account and salary doubled. Initially we might feel twice as rich as we were before, but prices would quickly rise to catch up to the new status quo. Before long, inflation would cause the real value of our money to return to its previous levels. Thus, increasing the supply of money increases the price levels. This idea is known as the quantity theory of money .

Inflation and the Money Supply

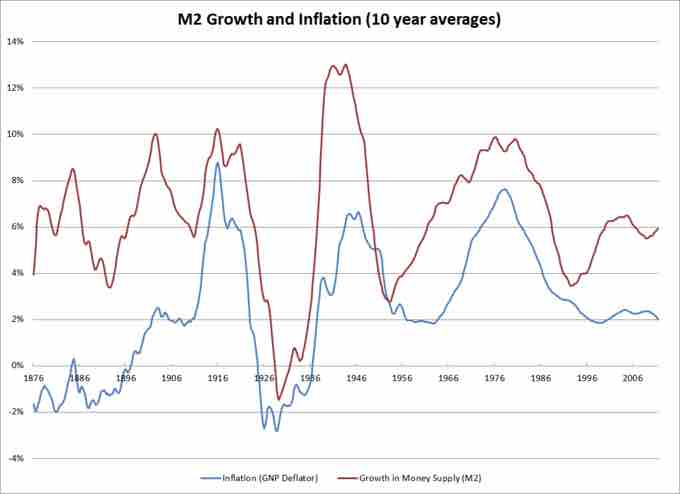

While the two variables are not exactly equivalent in the short run, over time the money supply has had a direct relationship to the level of inflation. This is consistent with the quantity theory of money.

In mathematical terms, the quantity theory of money is based upon the following relationship: M x V = P x Q; where M is the money supply, V is the velocity of money, P is the price level, and Q is total output. In the long run, the velocity of money (that is, how quickly money flows through the economy) and total output (that is, an economy's Gross Domestic Product) are exogenous. If all other factors are held constant, an increase in M will require an increase in P. Thus, an increase in the money supply requires an increase in the price level (inflation).

While most agree with the basic principles behind the quantity theory of money in the long run, many argue that it does not apply in the short run. John Maynard Keynes, for example, disagreed that V and Q are exogenous and stable in the near-term, and therefore a change in the money supply may not produce a proportional change in the price level. Instead, for example, an increase in the money supply could boost total output or cause the velocity of money to fall.