The Steady State Approximation

In our discussion so far, we have assumed that every reaction proceeds according to a mechanism that is made up of elementary steps, and that there is always one elementary step in the mechanism that is the slowest. This slowest step determines the rate of the entire reaction, and as such, it is called the rate-determining step. We will now consider cases in which the rate-determining step is either unknown or when more than one step in the mechanism is slow, which affects the overall reaction rate. Both cases can be addressed by using what is known as the steady state approximation.

Applying the Steady State Approximation

Recall our mechanism for the reaction of nitric oxide and oxygen:

Before, we assumed that the first step was fast, and that the second step was slow, thereby making it rate-determining. We will now proceed as if we had no such prior knowledge, and we do not know which, if either, of these steps is rate-determining. In such a case, we must assume that the reaction rate of each elementary step is equal, and the overall rate law for the reaction will be the final step in the mechanism, since this is the step that gives us our final products. In this case, the overall rate law will be:

However, this rate law contains a reaction intermediate, which is not permitted in this process. We need to write this rate law in terms of reactants only. In order to do so, we must assume that the state of the reaction intermediate, N2O2, remains steady, or constant, throughout the course of the reaction. The idea is analogous to a tub being filled with water while the drain is open. At a certain point, the flow of water into the tub will equal the flow of water out of the tub, so that the height of the water in the tub remains constant. In reality, however, water is flowing into and out of the tub at all times; the overall amount of water in the tub at any given time does not change. Our reaction intermediate, N2O2, is like the water in the tub, because it is being produced and consumed at equal rates. Therefore, we can rewrite our initial equilibrium step as the following combination of reverse reactions:

Here, k1 and k-1 are the rate constants for the forward and reverse reactions, respectively. With the steady state assumption, we can write the following:

Now, both of these rates can be written as rate laws derived from our elementary steps. We can write them as follows:

Note that the second side of the equation, which equals the rate of disappearance of our reaction intermediate N2O2, is written with two terms. The first term takes into account the disappearance of N2O2 in the reverse reaction of the initial step, and the second term takes into account the disappearance of N2O2 as a reactant in the second elementary step. We can rearrange this equation in terms of [N2O2]:

Lastly, now that we have [N2O2] in terms of our reactants only, we can substitute this entire expression into our equation for the overall rate law (equation 1 above). This yields the following:

Here we have our final rate law for the overall reaction. We had no knowledge of the rate-determining step, so we used the steady state approximation for our reaction intermediate, N2O2.

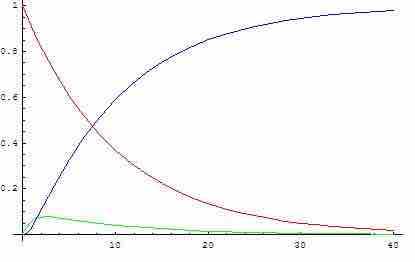

Concentration of reactants, products, and intermediates vs. time

Reactant concentrations are indicated in red, product concentrations are indicated in blue, and intermediate concentrations are indicated in green. Notice that after their initial production, the concentration of the reaction intermediates remains relatively constant (slope of green curve is approximately zero) throughout the course of the reaction.