In 2009, The United States was the world's largest manufacturer, with industrial output of $2.33 trillion. Its manufacturing output was greater than of Germany, France, India, and Brazil combined. Main industries included petroleum, steel, automobiles, construction machinery, aerospace, agricultural machinery, telecommunications, chemicals, electronics, food processing, consumer goods, lumber, and mining. The United States led the world in airplane manufacturing, which represented a large portion of U.S. industrial output. American companies, such as Boeing, Cessna, Lockheed Martin, and General Dynamics produced a vast majority of the world's civilian and military aircraft in factories stretching across the United States.

Manufacturing and Employment

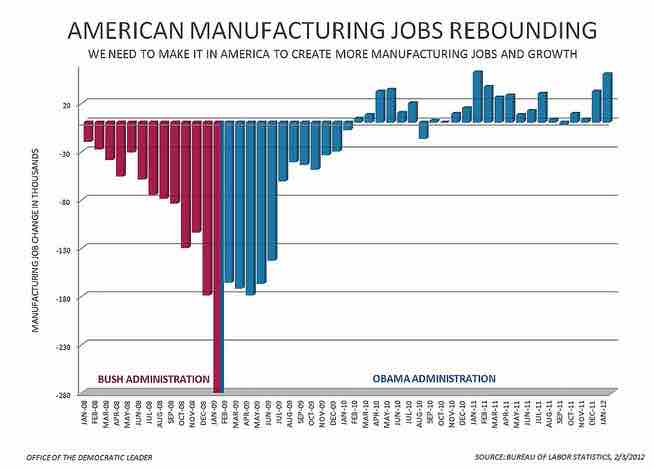

The Department of Labor announced that the economy added 243,000 jobs-including 50,000 in the manufacturing sector alone-in January 2012, and the unemployment rate fell to 8.3%. With 257,000 jobs added by private businesses, this marks the 23rd consecutive month of private sector job growth.

Yet, the manufacturing sector of the U.S. economy had been experiencing substantial job losses for several years. In January 2004, the number of such jobs stood at 14.3 million, down by 3.0 million jobs, or 17.5%, since July 2000 and about 5.2 million since the historical peak in 1979. Employment in manufacturing was its lowest since July 1950. The number of steel workers fell from 500,000 in 1980 to 224,000 in 2000.

The job loss during this continual volume growth has been attributed to multiple factors, including increased productivity, trade/outsourcing, and secular economic trends.

As much as we'd like to hear that manufacturing jobs are returning to the United States, the truth is that not as many of them will be created here as have been lost. It's not that there isn't the need for manufacturing jobs so much as it's businesses learning to do more with less, be it with more efficiency processes, or have more automation. Perry Sainati, founder and president of Belden International, explains that U.S. manufacturing has been transformed these days and is in the midst of a remarkable recovery because for three years running, manufacturing has not been about job growth; it's been about automation, process improvement, productivity, and it's been about quality. In fact, it's been about reinventing the very processes by which durable and disposable goods get manufactured.

What's more, it's been about streamlining our factories to the point that they're now among the most efficient in the world. Worker productivity on the United States is the highest in the world. That means for every man hour put in, we get more products built. It's to the point now here that we can even outproduce low-cost nations while doing it at a lower per unit cost. That means that even with cheaper labor, countries like China are finding themselves at an increasing cost disadvantage because American factories require a lot less labor to produce the same goods. It doesn't matter if workers in a low-cost country are paid an eighth of what American workers get paid if a single American worker can make the same amount of product as 10 workers in the low-cost country. The cost per unit is lower in the United States than in the low-cost country. At the moment, this scenario isn't true across the board, but it's getting there. As labor costs rise overseas, and transportation costs do likewise, it becomes increasingly more economical to build products here. However, as Sainati noted, pundits and politicians "say the word 'manufacturing' and they see in their minds' eyes things they used to see when they were kids. " But those days are long gone, and with them the old manufacturing stereotypes. The days of huge factories employing thousands upon thousands of men and women have been replaced with modern factories using lean manufacturing with better design, processes, and automation. As such, returning a manufacturing operation to the United States may cost a thousand workers in a low-cost country their jobs, but it won't create a thousand new manufacturing jobs in the U.S. It might only create 80, 100, or 120 jobs. It's not a 1:1 ratio because of the high productivity of American workers. It's likely it's going to remain that way, and we best get used to it.

While the United States service sector has grown, so has the manufacturing sector. De Rugy's data shows an increase in manufacturing output since 1975 and a decrease in employment in the manufacturing sector. What this suggests, off hand, is an increase in productivity per worker, which has released labor to the service sector and other industries. This is a good thing, because it means that we are much wealthier than we were in 1975 (not only more manufacturing, but a greatly expanded market in other sectors, as well).