Chapter 33

The Animal Body: Basic Form and Function

By Boundless

Every animal has a distinct body plan, adapted in response to environmental pressures, that limits its size and shape.

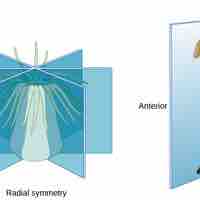

Animal body plans can have varying degrees of symmetry and can be described as asymmetrical, bilateral, or radial.

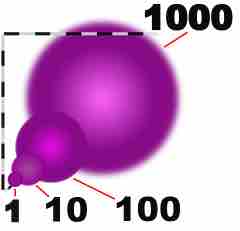

Animal shape and body size are influenced by environmental factors as well as the presence of an exoskeleton or an endoskeleton.

Less efficient diffusion in larger cells led to multicellular organisms with specialized tissues that supply nutrients and remove waste.

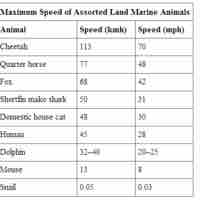

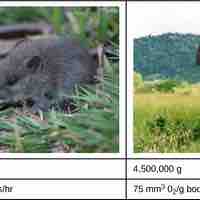

An animal's body size, activity level, and environment impacts the ways it uses and obtains energy.

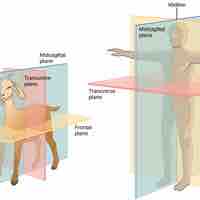

Vertebrates can be divided along different planes in order to reference the locations of defined cavities.

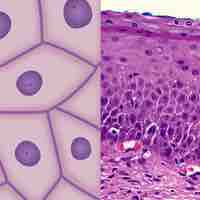

Epithelial tissues cover the outer surfaces of the body and the lumen of internal organs; they are classified by shape and number of layers.

Connective tissue is found throughout the body, providing support and shock absorption for tissues and bones.

Bone, adipose (fat) tissue, and blood are different types of connective tissue that are composed of cells surrounded by a matrix.

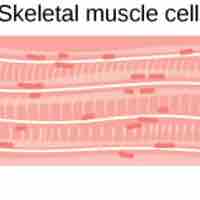

The function of muscle tissue (smooth, skeletal, and cardiac) is to contract, while nervous tissue is responsible for communication.

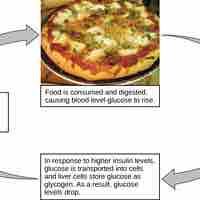

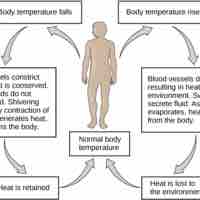

Homeostatic processes ensure a constant internal environment by various mechanisms working in combination to maintain set points.

Homeostasis is typically achieved via negative feedback loops, but can be affected by positive feedback loops, set point alterations, and acclimatization.

Animals use different modes of thermoregulation processes to maintain homeostatic internal body temperatures.

Animals have processes that allow for heat conservation and dissipation in order to maintain a homeostatic internal body temperature.