Philip II

Philip II of Macedon ruled Macedon and expanded the Macedonian empire into Greece, reigning from 359 until 336 BCE, when he was assassinated. Macedon was a kingdom to the north of mainland Greece and its inhabitants were considered barbarians by the Greeks. However, Philip II was a crafty politician and he carefully cultivated relationships and rivalries among the Greek city-states until, in 338 BCE, he began conquering Greece. Philip II was able to offer stability to the Greek poleis and to strengthen his ties to Greece. He claimed that he was a descendant of the Greek hero Herakles. He established Macedonian power over Greece, which passed to his son Alexander upon his death.

Alexander the Great

The son of Philip II, Alexander, inherited the throne of Macedon as Philip was preparing to campaign in Asia Minor against the Persian Empire in 336 BCE. Alexander followed through on his father's plans. In 333 BCE Alexander led his army in a ten year campaign across Asia Minor until reaching the Indus River in India conquering Egypt, Persia, and the Middle East. Along the way, Alexander established cities and practiced cultural assimilation. Instead of forcing conquered territories to adopt a new style of living, Alexander allowed cultures to keep their traditional ways of life, while introducing Greek culture and art to territories he conquered. This created a procession known as Hellenization, as new cultures such as Egyptian and Persian adopted and adapted Greek values.

Alexander desired to push into India and conquer the entirety of the continent, but his troops weary and exhausted from ten years of campaign protested. Finally, Alexander relented and turned home. While in Babylon, he became ill and died after twelve days of fever on June 23 in 323 BCE. His death marked the beginning of the Hellenistic period in Greece. Following Alexander's death, his generals and other close companions divided his empire, with each man taking their own territory to rule. The most powerful dynasties included the Attalids who ruled the kingdom of Pergamon in Ionia, the Seleucids who controlled Anatolia and the Near East, and the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt. The death of the last Ptolemaic ruler in Egypt, Cleopatra VII, and the annexation of Egypt by the Romans under Octavian, marked the end of the Hellenistic period.

Portraiture

Alexander very carefully controlled and crafted his portraiture. In order to maintain control and stability in his empire, he had to ensure that his people recognized him and his authority. Because of this, Alexander's portrait was set when he was very young, most likely in his teens, and it never varied throughout his life. To further control his portrait types, Alexander hired artists in different mediums such as painting, sculpture, and gem cutting to design and promote the portrait style of the medium. In this way, Alexander used art and artisans for their propagandistic value to support and provide a face and legitimacy to his rule.

The head of Alexander the Great demonstrates Alexander's portrait style . Busts of Alexander depict a young, ageless man. His eyes are cast upward to signify divine inspiration and his hair is tousled and unkempt, except for a perfect and characteristic part in the center of his hairline. The portraits of Alexander not only depicted him as ageless but also reflect his charisma and strength as a warrior and leader.

Bust of Alexander

Bust of Alexander. Marble. Ca. 350-323 BCE.

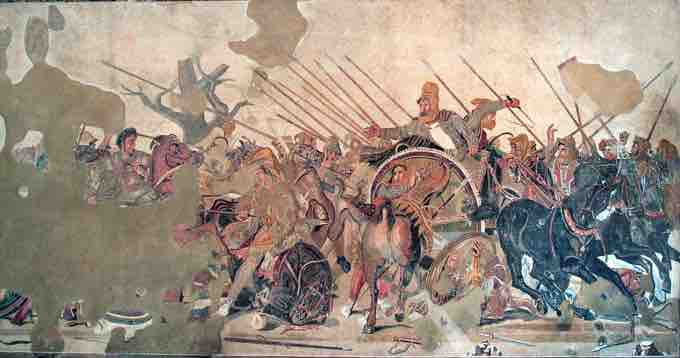

Alexander Mosaic

The Alexander Mosaic is a Roman floor mosaic from 100 BCE that was excavated from the House of the Faun in Pompeii. The mosaic depicts the Battle of Issus that occurred between the troops of Alexander the Great and King Darius III of Persia. The mosaic is believed to be a copy of a large scale panel painting by Aristides of Thebes or a fresco by the Philoxenos of Eretria from the late fourth century BCE.

Alexander Mosaic

Alexander Mosaic, Battle of Issus. Late second or first century BCE. Mosaic. House of the Faun, Pompeii, Italy.

The mosaic is remarkable. It depicts a keen sense of detail, dramatically unfolds the drama of the battle, and demonstrates the use of perspective and foreshortening. The two main characters of the battle are easily distinguishable and this portrait of Alexander may be one of his most recognizable. He wears a breastplate and an aegis, and his hair is characteristically tousled. He rides into battle on his horse, Bucephalo, leading his troops. Alexander's gaze remains focused on Darius and he appears calm and in control, despite the hectic battle happening around him. Darius III on the other hand commands the battle in desperation from his chariot, as his charioteer removes them from battle. His horses flee under the whip of the charioteer and Darius leans outward, stretching out a hand having just thrown a spear. His body position contradicts the motion of his chariot, creating tension between himself and his flight.

Other details in the mosaic include the expressions of the soldiers and horses such as a collapsed horse and his rider in the center of the battle to a terrified fallen Persian, whose expression is reflected on his shield. The shading and play of light in the mosaic, reflects the use of light and shadow in the original painting to create a realistic three-dimensional space. Horses and soldiers are shown in multiple perspectives from profile, to three quarter, to frontal, and one horse even faces the audience with his rump. The careful shading within the mosaic tesserae models the characters to give the figures mass and volume.