Fifteenth century Florence was the birthplace of Renaissance painting, which rejected the flatness and stylized nature of Gothic art in order to focus on naturalistic representations of the human body and landscapes. While Giotto is often referred to as the herald of the Renaissance, there was a break in artistic developments in Italy after his death, due largely to the Black Death. However, Florentine painting was revitalized the early 15th century, when the use of perspective was formalized by the architect Filippo Brunelleschi and adopted by painters as an artistic technique. The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts.

Many other important techniques commonly associated with Renaissance painting developed in Florence during the first half of the 15th century, including the use of realistic proportions, foreshortening (the artistic effect of shortening lines in a drawing to create the illusion of depth), sfumato (the blurring of sharp outlines by subtle and gradual blending to give the illusion of three-dimensionality), and chiaroscuro (the contrast between light and dark to convey a sense of depth).

The artist most widely credited with first pioneering these techniques in 15th century Florence is Masaccio (1401–1428), the first great painter of the Quattrocento period of the Italian Renaissance. Masaccio was deeply influenced by both Giotto's earlier innovations in solidity of form and naturalism and Brunelleschi's formalized use of perspective in architecture and sculpture. Masaccio is best known for his frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel, in which he employed techniques of linear perspective such as the vanishing point for the first time, and had a profound influence on other artists despite the brevity of his career.

Masaccio was friends with Brunelleschi and the sculptor Donatello, and collaborated frequently with the older and already renowned artist Masolino da Panicale (1383/4–1436) who traveled with him to Rome in 1423. From this point onwards, he eschewed the Byzantine and Gothic styles altogether, adopting traces of influence from ancient Greek and Roman art instead. These are evident in the cycle of frescoes he executed alongside Masolino for the Brancacci Chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. The two artists started working on the chapel in 1425, but their work was completed by Filippo Lippi in the 1480s.

The frescoes in their entirety represent the story of human sin and redemption from the fall of Adam and Eve to the works of St. Peter. Giotto's influence is evident in Masaccio's frescoes, particularly in the weight and solidity of his figures and the vividness of their expressions. Unlike Giotto, Masaccio utilized linear and atmospheric perspective, and made even greater use of directional light and the chiaroscuro technique, enabling him to create even more convincingly lifelike paintings than his predecessor. His style and techniques became profoundly influential after his death and were imitated by his successors.

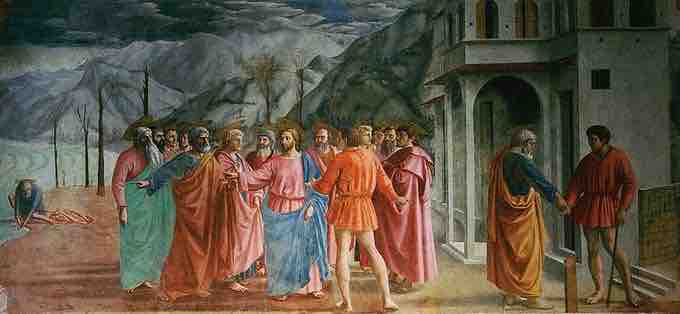

The Tribute Money, fresco in the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, 1425.

The Tribute Money is one of Masaccio's most famous frescoes from the Brancacci Chapel. Jesus and his apostles are depicted as neo-classical archetypes. The shadows of the figures fall away from the chapel window, as if the figures are lit by it; this is an added stroke of verisimilitude and shows Masaccio's innovative genius.