Background

Renaissance architecture is European architecture between the early 15th and early 17th centuries. It demonstrates a conscious revival and development of certain elements of classical thought and material culture. Stylistically, Renaissance architecture came after the Gothic period and was succeeded by the Baroque. During the High Renaissance, architectural concepts derived from classical antiquity were developed and used with greater surety.

The most representative architect is Bramante (1444–1514), who expanded the applicability of classical architecture to contemporary buildings, a style that was to dominate Italian architecture in the 16th century. In the late 15th century and early 16th century architects such as Bramante, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, and others showed a mastery of the revived style and ability to apply it to buildings such as churches and city palazzos, which were quite different from the structures of ancient times. Although studying and mastering the details of the ancient Romans was one of the important aspects of Renaissance architectural theory, the style also became more decorative and ornamental, with a widespread use of statuary, domes, and cupolas.

Forms and Purposes of Buildings

Renaissance architecture adopted obvious distinguishing features of classical Roman architecture. However, the forms and purposes of buildings had changed over time, as had the structure of cities, which is reflected in the resulting fusion of classical and 16th century forms. The plans of Renaissance buildings typically have a square, symmetrical appearance in which proportions are usually based on a module. The primary features of 16th century structures, which fused classical Roman technique with Renaissance aesthetics, were based in several foundational architectural concepts: facades, columns and pilasters, arches, vaults, domes, windows, and walls.

Foundational Architectural Concepts

Renaissance façades are symmetrical around their vertical axis. For instance, church façades of this period are generally surmounted by a pediment and organized by a system of pilasters, arches, and entablatures. The columns and windows show a progression towards the center. One of the first true Renaissance façades was the Cathedral of Pienza (1459–62), which has been attributed to the Florentine architect Bernardo Gambarelli (known as Rossellino).

Cathedral of Pienza

This Cathedral demonstrates one of the first true Renaissance façades.

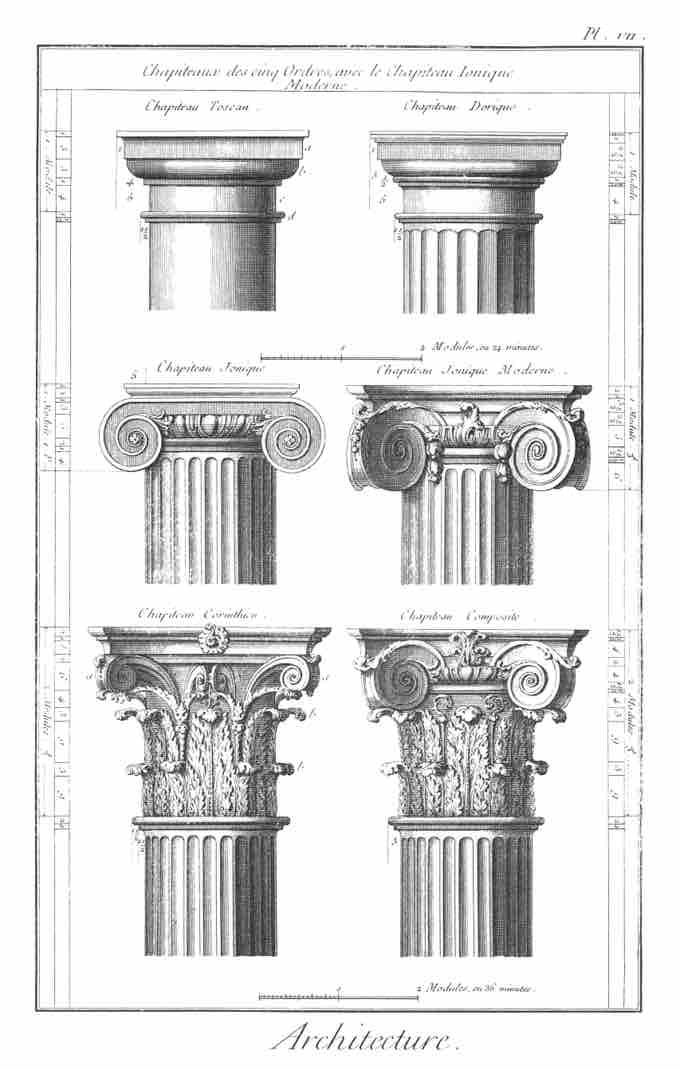

Renaissance architects also incorporated columns and pilasters, using the Roman orders of columns (Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite) as models. The orders can either be structural, supporting an arcade or architrave, or purely decorative, set against a wall in the form of pilasters. During the Renaissance, architects aimed to use columns, pilasters, and entablatures as an integrated system. One of the first buildings to use pilasters as an integrated system was the Old Sacristy (1421–1440) by Brunelleschi.

Classical Roman Columns

Orders of Architecture in the Greek Columns

The dome is used frequently in this period, both as a very large structural feature that is visible from the exterior, and also as a means of roofing smaller spaces where they are only visible internally. Domes had been used only rarely in the Middle Ages, but after the success of the dome in Brunelleschi's design for the Florence Cathedral and its use in Bramante's plan for St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, the dome became an indispensable element in Renaissance church architecture and carried over to the Baroque.

Dome of St. Peter's Basilica

The Dome of St Peter's Basilica, Rome is often cited as a foundational piece of Renaissance architecture.

Windows may be paired and set within a semicircular arch and may have square lintels and triangular or segmental pediments, which are often used alternately. Emblematic in this respect is the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, begun in 1517. In the Mannerist period, the "Palladian" arch was employed, using a motif of a high semicircular topped opening flanked with two lower square-topped openings. Windows were used to bring light into the building and in domestic architecture, to show the view. Stained glass, although sometimes present, was not a prevalent feature in Renaissance windows.

Palazzo Farnese

The Palazzo Farnese in Rome demonstrates the Renaissance window's particular use of square lintels and triangular and segmental pediments used alternatively.

Finally, external Renaissance walls were generally of highly finished ashlar masonry, laid in straight courses. The corners of buildings were often emphasized by rusticated quoins. Basements and ground floors were sometimes rusticated, as modeled on the Palazzo Medici Riccardi (1444–1460) in Florence. Internal walls were smoothly plastered and surfaced with white chalk paint. For more formal spaces, internal surfaces were typically decorated with frescoes.

Palazzo Medici Riccardi

Rusticated stone walls of the Renaissance Palazzo Medici Riccardi