Illustrated Books

Background

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration, such as decorated initials, borders (marginalia), and miniature illustrations. In the strict definition of the term, an illuminated manuscript only refers to manuscripts decorated with gold or silver. However, the term is now used to refer to any decorated or illustrated manuscript from the Western traditions in both common usage and modern scholarship. The earliest surviving substantive illuminated manuscripts are from the period 400 to 600 CE and were initially produced in Italy and the Eastern Roman Empire. The significance of these works lies not only in their inherent art historical value, but also in the maintenance of literacy offered by non-illuminated texts as well. Had it not been for the monastic scribes of Late Antiquity who produced both illuminated and non-illuminated manuscripts, most literature of ancient Greece and Rome would have perished in Europe.

The majority of the surviving illuminated manuscripts are from the Middle Ages, and hence, the majority of these manuscripts are of a religious nature. Illuminated manuscripts were written on the best quality of parchment, called vellum. By the sixteenth century, the introduction of printing and paper rapidly led to the decline of illumination, although illuminated manuscripts continued to be produced in much smaller numbers for the very wealthy. Early medieval illuminated manuscripts are the best examples of medieval painting, and indeed, for many areas and time periods, they are the only surviving examples of pre-Renaissance painting.

Insular Art in Illustrated Books

Driving from the Latin word for island (insula), Insular art is characterized by detailed geometric designs, interlace, and stylized animal decoration spread boldly across illuminated manuscripts. Insular manuscripts sometimes take a whole page for a single initial or the first few words at beginnings of gospels. This technique of allowing decoration a right to roam was later influential on Romanesque and Gothic art. From the seventh through ninth centuries, Celtic missionaries traveled to Britain and brought with them the Irish tradition of manuscript illumination, which came into contact with Anglo-Saxon metalworking. New techniques employed were filigree and chip-carving, while new motifs included interlace patterns and animal ornamentation.

One illuminated manuscript that represents the pinnacle of Insular Art is the Book of Kells (Irish: Leabhar Cheanannais), created by Celtic monks in 800, or slightly earlier. Also known as the Book of Columba, The Book of Kells is considered a masterwork of Western calligraphy, with its illustrations and ornamentation surpassing that of other Insular Gospel books in extravagance and complexity. The Book of Kells's decoration combines traditional Christian iconography with the ornate swirling motifs typical of Insular art. Figures of humans, animals, and mythical beasts, together with Celtic knots and interlacing patterns in vibrant colors, enliven the manuscript's pages. Many of these minor decorative elements are imbued with Christian symbolism. The manuscript comprises 340 folios made of high-quality vellum, and the unprecedentedly elaborate ornamentation that covers them includes ten full-page illustrations and text pages that are vibrant with decorated initials and interlinear miniatures and mark the furthest extension of the anti-classical and energetic qualities of Insular art.

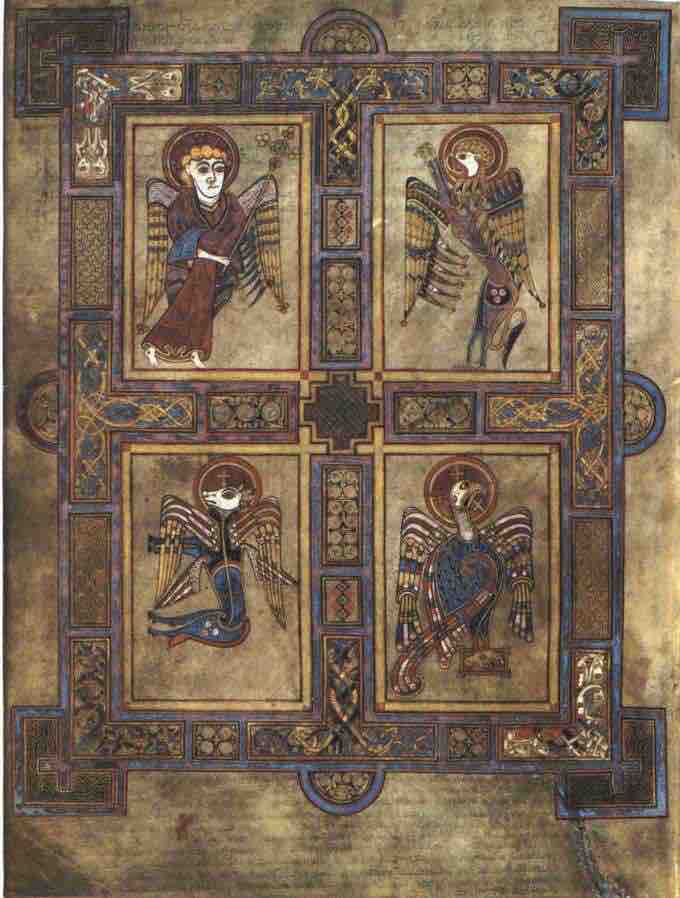

Book of Kells: Folio 27v

Folio 27v contains the symbols of the Four Evangelists (Clockwise from top left): a man (Matthew), a lion (Mark), an eagle (John), and an ox (Luke). The Evangelists are placed in a grid and enclosed in an arcade, as is common in the Mediterranean tradition. However, notice the elaborate geometric and stylized ornamentation in the arcade that highlights the Insular aesthetic.

The Insular majuscule script of the text itself in the Book of Kells appears to be the work of at least three different scribes. The lettering is in iron gall ink, and the colors used were derived from a wide range of substances, many of which were imported from distant lands. The text is accompanied by many full-page miniatures, while smaller painted decorations appear throughout the text in unprecedented quantities. The decoration of the book is famous for combining intricate detail with bold and energetic compositions. The illustrations feature a broad range of colors. Purple, lilac, red, pink, green, and yellow used most often. As is usual with Insular work, there was no use of gold or silver leaf in the manuscript. However, the pigments for the illustrations, which included red and yellow ochre, green copper pigment (sometimes called verdigris), indigo, and lapis lazuli, were very costly and precious. They were imported from the Mediterranean region and, in the case of the lapis lazuli, from northeast Afghanistan.

The decoration of the first eight pages of the canon tables is heavily influenced by early Gospel Books from the Mediterranean, where it was traditional to enclose the tables within an arcade. Although influenced by this Mediterranean tradition, the Kells manuscript presents this motif in an Insular spirit, where the arcades are not seen as architectural elements but rather become stylized geometric patterns with Insular ornamentation. Furthermore, such complicated knot work and interweaving found in the Kells manuscript echo the metalwork and stone carving works that characterized the artistic legacy of the Insular period.

The Book of Kells

This example from the manuscript (folio 292r) shows the lavishly decorated section that opens the Gospel of John.

Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts form a significant part of Insular art and reflect a combination of influences from the Celtic styles that arose when the Anglo-Saxons encountered Irish missionary activity. A different mixture is seen in the opening from the Stockholm Codex Aureus, where the evangelist portrait reflects an adaptation of classical Italian style, while the text page is mainly in Insular style, especially in the first line, with its vigorous Celtic spirals and interlace. This is one of the so-called "Tiberius Group" of manuscripts, which leaned towards the Italian style. It is, in the usual chronology, the last English manuscript in which trumpet spiral patterns are found.

The Stockholm Codex Aureus

The evangelist portrait from the Stockholm Codex Aureus, one of the "Tiberius Group," that shows the Insular style and classicizing continental styles that combined and competed in early Anglo-Saxon manuscripts.

The Beatus Manuscripts

The Commentary on the Apocalypse was originally a Mozabaric eighth-century work by the Spanish monk and theologian Beatus of Liébana. Often referred to simply as the Beatus, it is used today to reference any of the extant manuscript copies of this work, especially any of the 26 illuminated copies that have survived. The historical significance of the Commentary is made even more pronounced since it included a world map, offering a rare insight into the geographical understanding of the post-Roman world. Considered together, the Beatus codices are among the most important Spanish and Mozarabic medieval manuscripts, and have been the subject of extensive scholarly and antiquarian inquiry.

Beatus World Map

The world map from the Saint-Sever Beatus, measuring 37 x 57 cm. This was painted c. 1050 as an illustration to Beatus's work at the Abbey of Saint-Sever in Aquitaine, on the order of Gregori de Montaner, Abbot from 1028 to 1072.

Though Beatus might have written these commentaries as a response to Adoptionism in the Hispania of the late 700s, many scholars believe that the book's popularity in monasteries stemmed from the Arabic-Islamic conquest of the Iberian peninsula, which some Iberian Christians took as a sign of the Antichrist. Not all of the Beatus manuscripts are complete, and some exist only in fragmentary form. However, the surviving manuscripts are lavishly decorated in the Mozarabic, Romanesque, or Gothic style of illumination.

Mozarabic art refers to art of Mozarabs, Iberian Christians living in Al-Andalus who adopted Arab customs without converting to Islam during the Islamic invasion of the Iberian peninsula (from the eighth through the eleventh century). Mozarabic art features a combination of (Hispano) Visigothic and Islamic art styles, as in the Beatus manuscripts, which combine Insular art illumination forms with Arabic-influenced geometric designs.

Beatus of Liébana. Judgement of Babylon.

From Beatus Apocalypse.