Classical Greece was a 200-year period in Greek culture lasting from the fifth through fourth centuries BCE. This Classical period, following the Archaic period and succeeded by the Hellenistic period, had a powerful influence on the Roman Empire and greatly influenced the foundations of the Western Civilization. Much of modern Western politics and artistic thought, such as architecture, scientific thought, literature, and philosophy, derives from this period of Greek history.

Panel Painting

Panel painting is the painting on flat panels of wood, either a large single piece or several joined together. Because of their organic nature many panel paintings no longer exist. Panel paintings were usually done in encaustic or tempera and were displayed in the interior of public buildings, such as in the pinacoteca of the Propylaea of the Athenian Acropolis.

The earliest known panel paintings are the Pitsa Panels that date to the Archaic period between 540 and 530 BCE; however panel painting continued throughout the Classical Period. The painter Apollodorus was considered by the Greeks and Romans to be one of the best painters of the Early Classical period, although none of his work survived. He is credited for the use of creating shadows by a technique known as skiagraphia. The technique layers crosshatching and contour liners to add perspective to the scene and is similar to the Renaissance technique of chiaroscuro.

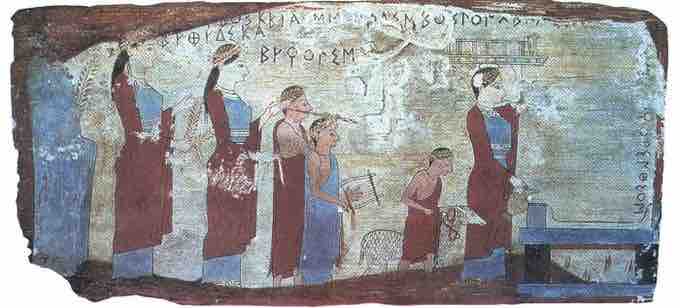

Pista Panel, c. 540-530 BCE. Athens, Greece.

The Pista Panels are the earliest known panel paintings, and date to the Archaic period between 540 and 530 BCE.

Tomb painting

Tomb painting was another popular method of painting, which due to its fragile nature has often not survived. However a few examples do remain, including the 480 BCE Tomb of the Diver and the wall paintings from the royal Macedonian tombs in Vergina that date to the mid-fourth century BCE. A comparison between the paintings demonstrate how painting followed sculptural development in regards to the rendering of the human body.

The Tomb of the Diver is from a small necropolis in Paestum, Italy, which was then the Greek colony of Poseidonia, and dates from the beginning of the Classical period. The tomb depicts a symposium scene on its walls and an image of diver on the inside of the covering slab. The images are painted in true fresco with a limestone mortar. The scene of the diver is simple image with a small landscape of trees, water, and the diver's platform. The diver is nude and his body is simply defined through the use of line and color. The bodies of the men at the symposium more accurately demonstrate an Archaic reliance on line to model the form of the body and the draping of their clothing.

Tomb of the Diver, Fresco. c. 480 BCE, Paestum, Italy.

This is the symposium scene painted on the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum.

Compared to the wall paintings from the tombs at Vergina, the Early Classical tomb painting is static and rather Archaic. The frescos from Vergina depict figures in a full painted version of the High Classical style. For example, there is an image believed to depict King Philip II on a chariot pulled by two horses . The fresco is poorly preserved but one is able to see on Philip's horse the modeling of the animals produced by the color shading and a suggestion of perspective when looking at the chariot. The artist relies on the shades and hues of his paints to create depth and a life-like feeling in the painting.

Man on a Chariot. Wall painting. c. 4th c. BCE. Vergina, Greece.

The frescos from Vergina depict figures in a full painted version of the High Classical style.

One of the quintessential wall paintings at Vergina is Hades Abducting Persephone. The painted scene appears similar to the Late Classical sculptural style and the dynamic, emotion-filled composition seems to predict the style of Hellenistic sculpture. The scene depicts Hades on his chariot, grasping on to Persephone's nude torso as the pair ride away. The colors are faded and faint, but the bright red drapery worn by Persephone is still easily identifiable. Lines and shading emphasize its folds. The style appears almost impressionistic, especially when examining Persephone's face and hair. Persephone and Hades create a tension filled chiastic composition, as Hades races to the left, against the pull of Persephone's outward, desperate reach to the right.

Hades Abducting Persephone. Wall painting. c. 4th c. BCE. Vergina, Greece.

One of the quintessential wall paintings at Vergina is a scene of Hades abducting Persephone.

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedonia (356-323 BCE), better known as Alexander the Great, very carefully controlled and crafted his portraiture. In order to maintain control and stability in his empire, he had to ensure that his people recognized him and his authority. Because of this, Alexander's portrait was set when he was very young, most likely in his teens, and it never varied throughout his life. To further control his portrait types, Alexander hired artists in different media such as painting, sculpture, and gem cutting to design and promote the portrait style of the medium. In this way, Alexander used art and artisans for their propagandistic value to support and provide a face and legitimacy to his rule.

Alexander Mosaic

The Alexander Mosaic is a Roman floor mosaic from approximately 100 BCE that was excavated from the House of the Faun in Pompeii. The mosaic depicts the Battle of Issus that occurred between the troops of Alexander the Great and King Darius III of Persia. The mosaic is believed to be a copy of a large scale panel painting by Aristides of Thebes or a fresco by the Philoxenos of Eretria from the late fourth century BCE.

Alexander Mosaic (Battle of Issus)

Roman. House of the Faun, Pompeii. Late second or third century BCE. Believed to be a copy of a fresco by Philoxenos of Eretria or a panel painting by Aristides of Thebes (late fourth century BCE). Alexander is depicted in profile at the far left.

The mosaic is remarkable. It depicts a keen sense of detail, dramatically unfolds the drama of the battle, and demonstrates the use of perspective and foreshortening. The two main characters of the battle are easily distinguishable and this portrait of Alexander may be one of his most recognizable. He wears a breastplate and an aegis, and his hair is characteristically tousled. He rides into battle on his horse, Bucephalo, leading his troops. Alexander's gaze remains focused on Darius and he appears calm and in control, despite the hectic battle happening around him. Darius III on the other hand commands the battle in desperation from his chariot, as his charioteer removes them from battle. His horses flee under the whip of the charioteer and Darius leans outward, stretching out a hand having just thrown a spear. His body position contradicts the motion of his chariot, creating tension between himself and his flight.

Other details in the mosaic include the expressions of the soldiers and horses such as a collapsed horse and his rider in the center of the battle to a terrified fallen Persian, whose expression is reflected on his shield. The shading and play of light in the mosaic, reflects the use of light and shadow in the original painting to create a realistic three-dimensional space. Horses and soldiers are shown in multiple perspectives from profile, to three quarter, to frontal, and one horse even faces the audience with his rump. The careful shading within the mosaic tesserae models the characters to give the figures mass and volume.