Temples of the Archaic Period

Stone temples were first built during the Archaic period in ancient Greece. Before this, they were constructed out of mud-brick and wood--simple structures that were rectangular or semi-circular in shape--which may have been enhanced with a few columns and a porch. The Archaic stone temples took their essential shape and structure from both these previous wooden temples and the shape of a Mycenaean megaron.

Temple design

The standard form of a Greek temple was established and then refined through the Archaic and Classical period. Most temples were rectilinear in shape and stood on a raised stone platform, known as the stylobates, which usually had two or three stairs. One notable exception to this standard was the circular tholos dedicated to Apollo at Delphi. Columns were placed on the edge of the stylobate in a line or colonnade, which was peripteral and ran around the naos (inner chamber that holds a cult statue) and its porches,. Columns were placed on the edge of the stylobate in a line or colonnade, which was peripteral and ran around the (inner chamber that holds a cult statue) and its porches, completely surrounding the temple.

Temple Plans

These illustrations show various examples of Greek temples. The standard form of a Greek temple was established and then refined through the Archaic and Classical periods.

The main portion of the temple was the naos. To the front of the naos was the pronaos, or front porch. A door between the naos and pronaos provided access to the cult statue. Columns, known as prostyle, often stood in front of the pronaos. These were often aligned with molded projections to the end of the pronaos's wall, called the anta (plural antae). Such aligned columns were referred to as columns in antis. A rear room, called the opisthodomos, was on the other side of the temple and naos. A wall separated the naos and opisthodomos completely. The opisthodomos was used as a treasury and held the votives and offerings left at the temple for the god or goddess. It also had a set of prostyle columns in antis that completed the symmetrical appearance of the temple.

While this describes the standard design of Greek temples, it is not the most common form found. The first stone temples varied significantly as architects and engineers were forced to determine how to properly support a roof with such a wide span. Later architects, such as Iktinos and Kallikrates who designed the Parthenon, tweaked aspects of basic temple structure to better accommodate the cult statue. All temples, however, were built on a mathematical scale and every aspect of them is related to one another through ratios.

For instance, most Greek temples (except the earliest) followed the equation 2x + 1 = y when determining the number of columns used in the peripteral colonnade. In this equation, x stands for the number of columns across the front, the shorter end, while y designates the columns down the sides. The number of columns used along the length of the temple was twice the number plus one the number of columns across the front. Due to these mathematical ratios, we are able to accurately reconstruct temples from small fragments.

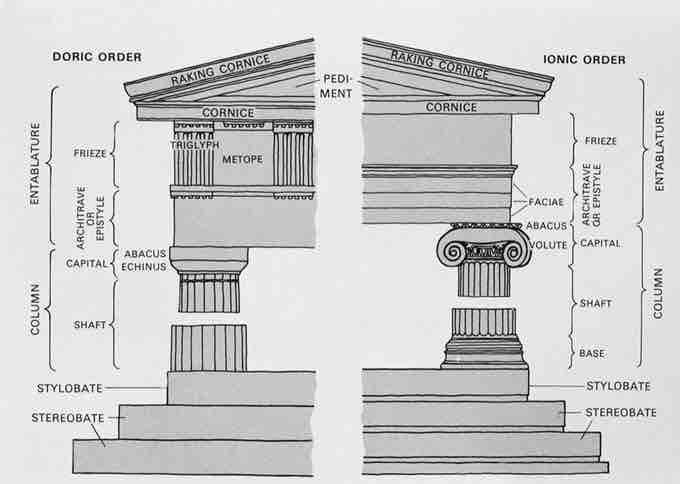

Doric order

The style of Greek temples is divided into three different and distinct orders, the earliest of which is the Doric order . These temples had columns which rested directly on the stylobate without a base. Their shafts were fluted with twenty parallel grooves that tapered to a sharp point. The capitals of Doric columns had a simple, unadorned square abacus and a flared echinus that was often short and squashed. Doric columns are also noted for the presence of entasis, or bulges in the middle of the column shaft. This was perhaps a way to correct optical illusion or to emphasize the weight of the entablature above, held up by the columns.

Doric and Ionic Order

This drawing illustrates the stylistic differences between the Doric and Ionic Order.

The Doric entablature was also unique to this style of temples. The frieze was decorated with alternating panels of triglyphs and metopes. The triglyphs were decorative panels with three grooves or glyphs that gave the panel its name. The stone triglyphs mimicked the head of wooden beams used in earlier temples. Between the triglyphs were the metopes.

Decorative spaces

Sculptors used the metope spaces to depict mythological occurrences, often with historical or cultural links to the site on which the temple stood.

Herakles fights the Cretan Bull

This is one of the metopes from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. It is one of the Twelve Labors depicted on the temple.

On the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (constructed between 470BC and 456BC), the choice to sculpt the Twelve Labors of Herakles was in direct correlation with the site's Olympic Games and the spirit of triumph in physical challenge. Most sculptors attempted to use the limited and angular space of metopes to show distinct moments that filled the shape, but not all were successful in doing so. Another space used for decoration was the pediment at each end of the temple. Due to the larger space afforded by these sections, the sculptors often chose to depict larger and more eventful scenes.

The sculptures from the pediments on the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina

These scenes show fight scenes between Greeks and Trojans, such as those described in Homer's Iliad.

The shape of the pediment made it difficult to arrange figures in a coherent and cohesive scene, so sculptors placed the most prominent ones in the apex (the highest point of the triangle). All of these decorative sculptures would have been painted in bright colors and recognizable to onlookers.

Paestum, Italy

The Greek colony at Poseidonia (now Paestum) in Italy, built two Archaic Doric temples that are still standing today .

Temple of Hera II and Temple of Hera I, Paestum, Italy. c. 500-460 BCE.

The Greek colony at Poseidonia (now Paestum) in Italy, built two Archaic Doric temples that are still standing today.

The first, the Temple of Hera I, was built in 550 BCE and differs from the standard Greek temple model dramatically. It is peripteral, with nine columns across its short ends and 18 columns along each side. The opisthodomos is accessed through the naos by two doors. There are three columns in antis across the pronaos. Inside the naos is a row of central columns, built to support the roof. The cult statue was placed at the back, in the center, and would be blocked from view by the row of columns. When examining the columns, they are large and heavy, and spaced very close together. This further denotes the Greeks unease with building in stone and the need to properly support a stone entablature and heavy roof. The capitals of the columns are round, flat, and pancake-like.

The Temple of Hera II, built almost a century later in 460 BCE, began to show the structural changes that demonstrated the Greek's comfort and developing understanding of building in stone, as well as the beginnings of a Classical temple style. In this example, the temple was fronted by six columns, with 14 columns along its length. The opisthodomos was separated from the naos and had its own entrance and set of columns in antis. A central flight of stairs led from the pronaos to the naos and the doors opened to look upon a central cult statue. There were still interior columns; however they were moved to the side, permitting prominent display of the cult statue.

Aegina

The temple of Aphaia on the island of Aegina is an example of Archaic Greek temple design as well as of the shift in sculptural style between the Archaic and Classical periods. Aegina is a small island in the Saronic Gulf within view of Athens; in fact, Aegina and Athens were rivals. While the temple was dedicated to the local god Aphaia, the temple's pediments depicted scenes of the Trojan War to promote the greatness of the island. These scenes involve Greek heroes who fought at Troy -- Telamon and Peleus, the fathers of Ajax and Achilles. In an antagonistic move, the battle scenes on the pediments are overseen by Athena, and the temple's dedicated deity, Aphaia, does not appear on the pediment at all. While very little paint remains now, the entire pediment scene, triglyphs and metopes, and other parts of the temple would have been painted in bright colors.

Temple of Aphaia at Aegina (c. 500-490 BCE)

The Temple of Aphaia at Aegina as it stands today.

Temple Design

The Temple of Aphaia is one of the last temples with a design that did not conform to standards of the time. Its colonnade has six columns across its width and twelve columns down its length. The columns have become more widely spaced and also more slender. Both the pronaos and opisthodomos have two prostyle (free-standing) columns in antis and exterior access, although both lead into the temple's naos. Despite the connection between the opisthodomos and the naos, the doorway between them is much smaller than the doorway between the naos and the pronaos. As in the Temple of Hera II, there are two rows of columns on either side of the temple's interior. In this case there are five on each side, and each colonnade has two stories. A small ramp interrupts the stylobate at the center of the temple's main entrance.

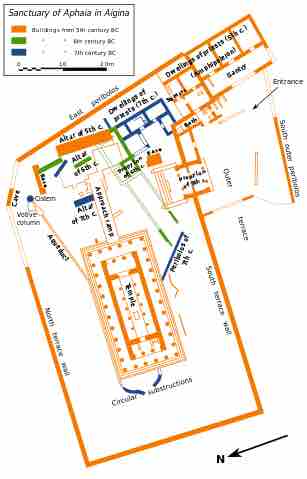

Plan of the sanctaury of the Temple of Aphaia

Ground plan of the Temple of Aphaia and the surrounding area