Sculpture in the Archaic Period

This developed rapidly from its early influences, becoming more natural and showing a developing understanding of the body, specifically the musculature and the skin. Close examination of the style's development allows for precise dating.

Most statues were commissioned as memorials and votive offerings or as grave markers, replacing the vast amphora (two-handled, narrow-necked jars used for wine and oils) and kraters (wide-mouthed vessels) of the previous periods, yet still typically painted in vivid colors.

Kouroi

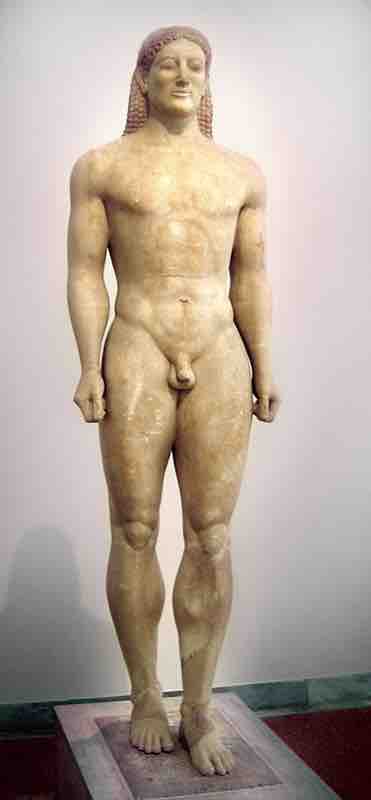

Kouroi statues (singular, kouros), depicting idealized, nude male youths, were first seen during this period. Carved in the round, often from marble, kouroi are thought to be associated with Apollo; many were found at his shrines and some even depict him. Emulating the statues of Egyptian pharaohs, the figure strides forward on flat feet, arms held stiffly at its side with fists clenched. However, there are some importance differences: kouroi are nude, mostly without identifying attributes and are free-standing.

Early kouroi figures share similarities with Geometric and Orientalizing sculpture, despite their larger scale. For instance, their hair is stylized and patterned, either held back with a headband or under a cap. The New York Kouros strikes a rigid stance and his facial features are blank and expressionless. The body is slightly molded and the musculature is reliant on incised lines.

New York Kouros, c. 600 BCE.

New York Kouros. Marble. Origin unknown.

As kouroi figures developed, they began to lose their Egyptian rigidity and became increasingly naturalistic. The kouros figure of Kroisos, an Athenian youth killed in battle, still depicts a young man with an idealized body. This time though, the body's form shows realistic modeling. The muscles of the legs, abdomen, chest and arms appear to actually exist and seem to function and work together. Kroisos's hair, while still stylized, falls naturally over his neck and onto his back, unlike that of the New York Kouros, which falls down stiffly and in a single sheet. The reddish appearance of his hair reminds the viewer that these sculptures were once painted.

Kroisos, c. 530 BCE.

Kroisos, from the Anavysos Group. Marble. Greece.

Archaic Smile

Kroisos's face also appears more naturalistic when compared to the earlier New York Kouros. His cheeks are round and his chin bulbous; however, his smile seems out of place. This is typical of this period and is known as the Archaic smile. It appears to have been added to infuse the sculpture with a sense of being alive and to add a sense of realism.

Kore

A kore (plural korai) sculpture depicts a female youth. Whereas kouroi depict athletic, nude young men, the female korai are fully-clothed, in the idealized image of decorous women. Unlike men, whose bodies were perceived as public, belonging to the state, women's bodies were deemed private, belonging to their fathers (if unmarried) or husbands. However, they also have Archaic smiles, with arms either at their sides or with an arm extended, holding an offering. The figures are stiff and retain more block-like characteristics than their male counterparts. Their hair is also stylized, depicted in long strands or braids that cascade down the back or over the shoulder.

The Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE) depicts a young woman wearing a peplos, a heavy wool garment that drapes over the whole body, obscuring most of it. A slight indentation between the legs, a division between her torso and legs and the protrusion of her breasts merely hint at the form of the body underneath. Remnants of paint on her dress tell us that it was painted yellow with details in blue and red that may have included images of animals. The presence of animals on her dress may indicate that she is the image of a goddess, perhaps Artemis, but she may also just be a nameless maiden.

Peplos Kore

Reconstruction of the paint on the Peplos Kore.

Later korai figures also show stylistic development, although the bodies are still overshadowed by their clothing. The example of a Kore (520-510 BCE) from the Athenian Acropolis shows a bit more shape in the body such as defined hips instead of a dramatic belted waistline, although the primary focus of the kore is on the clothing and the drapery. This kore figure wears a chiton (a woolen tunic), a himation (a lightweight undergarment), and a mantle (a cloak). Her facial features are still generic and blank, and she has an Archaic smile. Even with the finer clothes and additional adornments such as jewelry, the figure depicts the idealized Greek female, fully clothed and demure.

Acropolis Kore, c. 520-510 BCE.

Wearing a chiton and himation. Marble. Athens, Greece.

Pedimental Sculpture: The Temple of Artemis at Corfu

This sculpture, initially designed to fit into the space of the pediment, underwent dramatic changes during the Archaic period, seen later at Aegina. The west pediment at the Temple of Artemis at Corfu depicts not the goddess of the hunt, but the Gorgon Medusa with her children Pegasus, a winged horse, and Chrysaor, a giant welding a golden sword surrounded by heraldic lions. Medusa faces outwards in a challenging position, believed to be apotropaic (warding off evil). Additional scenes include Zeus fighting a Titan, and the slaying of Priam, the king of Troy, by Neoptolemos. These figures are scaled down in order to fit into the shrinking space provided in the pediment.

Pediment of the Temple of Artemis at Corfu, c. 600-580 BCE.

Sculpture and reconstruction of the west pediment. Limestone. Corfu, Greece.

Pedimental Sculpture: The Temple of Aphaia at Aegina

Sculpted approximately one century later, the pedimental sculptures on the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina gradually grew more naturalistic than their predecessors at Corfu. The dying warrior on the west pediment (c. 490 BCE) is a prime example of Archaic sculpture. The male warrior is depicted nude, with a muscular body that shows the Greeks' understanding of the musculature of the human body. His hair remains stylized with round, geometric curls and textured patterns. However, despite the naturalistic characteristics of the body, the body does not seem to react to its environment or circumstances. The warrior props himself up with an arm, and his whole body is tense, despite the fact that he has been struck by an arrow in his chest. His face, with its Archaic smile, and his posture conflict with the reality that he is dying.

Dying Warrior, c. 490 BCE.

Marble, West Pediment of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina.

Aegina: Transition between Styles

The dying warrior on the east pediment (c. 480 BCE) marks a transition to the new Classical style. Although he bears a slight Archaic smile, this warrior actually reacts to his circumstances. Nearly every part of him appears to be dying. Instead of propping himself up on an arm, his body responds to the gravity pulling on his dying body, hanging from his shield and attempting to support himself with his other arm. He also attempts to hold himself up with his legs, but one leg has fallen over the pediment's edge and protrudes into the viewer's space. His muscles are contracted and limp, depending on which ones they are, and they seem to strain under the weight of the man as he dies.

Dying Warrior, c. 480 BCE.

Marble, East Pediment of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina.