Photographer Carol Highsmith has donated her life’s work of tens of thousands of photos to the Library of Congress during her decades long career. Originally trained as an architectural photographer, Highsmith embarked on an ambitious project to photograph every American state in the 1980s, traveling up to ten months a year across the country to photograph small towns, big cities, roadside attractions, and everything in between. Highsmith’s photographs have appeared in films and television as well as in books, gallery exhibits, and even on a postage stamp. In 2009, Highsmith was chosen as one of four women highlighted as part of the Library of Congress’s Women’s History Month profiles. Highsmith has been in the news lately due to her lawsuit regarding Getty Images’s use of her images.

Highsmith’s project predates our work as Creative Commons, but her work is very much in the spirit of our community. By removing copyright restrictions from her photographs, Highsmith is engaged in the important work of growing a robust commons built on gratitude and usability; her singular archive at the Library of Congress is a testament to one woman’s passion and generosity. In this interview with CC, Highsmith shared some of her favorite photographs and stories from the road, her inspirations, and why she has hope in a new generation of innovation.

Over your career you’ve chosen to give away a lot of your work to the commons. Why is that? Can you talk about why you decided to share your work, and why in particular with the Library of Congress?

I am following in the footsteps of a woman named Frances Benjamin Johnston. She worked at the turn of the last century, and her photographs are kind of the cornerstone of the Library of Congress prints and photographs division. She was an architectural photographer like I am but she also did people and other things, also like I do.

I thought it was such a good idea, that it makes sense for me to share my work. There is no better place for preservation than the Library of Congress, so I decided to follow in her footsteps and I’ve never looked back. I’ve traveled America for 35 to 40 years now… I thought it would be a good idea to have a collection where someone knew what they were doing and cared about what things looked like and to give that to the people of the world.

Film is almost gone, and over time, will digital move on as well? Will we have a record of our country? The LOC has images from early portraits taken in America, 176 years ago to what I’m shooting now, so my collection makes their collection richer. It is considered the most historic photographic collection on earth and I’m honored and humbled that I’m in that collection.

Did you always imagine that the photos would be widely available, or did you think of it initially as a physical archive?

When I started giving, I wanted to give something that wouldn’t sit for years before it got scanned (at the time I was giving film.) We decided that I would make prints, because at that time scanning was not a common thing. As it became easier for me to scan, then I started scanning my own work. Finally, I gave a very large swath of my 4×5 collection, the cream of it, scanned on a very sophisticated scanner. I have always had my hand in it because I’ve always felt that it was extremely important that if I was going to give, that I needed the images to be up sooner rather than years and years from now.

The other turning point was when I decided that I should scan my own work so people could use them now in addition to donating them to the Library of Congress. That was extremely important to me and I’m very glad I did it.

It’s important to me to bring quality to the map so that these images can be used for hundreds of years. Now, obviously technology is going to change, but as long as I’m on the edge of technology, it’s a good thing for everyone who’s going to use it.

Have there been any surprising outcomes you’ve seen from working with the Library of Congress?

Well, I am very honored that [the Library of Congress] is holding my hand.

I came up with the idea [to do long term studies of states] around 2008– I was traveling around America doing books for Random House for years, and I would always race through towns and I wanted to stay longer and do more. One day I came up with the idea that maybe if I found funding, it would help me stay longer, and I could photograph more thoroughly. I went to the Library of Congress to see if there was a way I could raise some funds for me to actually go out across America and rather than just catch the best of a city or a town or a rural area that I actually stay for a while and try to do interiors and exteriors and really research it. [After my first project in Alabama,] I realized what a difference that made when I could actually take my time. I could be there when it wasn’t raining!

I was a little nervous about it at the very beginning because I didn’t know [Alabama] very well, but it turned out that I love the state and I learned so much. I gave about 4,000 or 5,000 images of Alabama to the Library of Congress and I think they started looking at me differently as well and saw that I was really serious about what I wanted to do.

You’ll go to a state and you’ll donate 4,000 or 5,000 images. How do you choose those images? Is it everything you’ve taken?

Not by a long shot! If I’m donating 4,000 images I’ve probably taken 50,000. I can take and take and take, work and work and work. The most important thing is that I give them the best. Everything has to be scanned and color corrected, and metadata has to go on it. It was a tremendous amount of work, but we set up all the systems, and I realized how valuable it was. People from the state can use them, people from all over the world can use them. [They also put out a collection of my born digital images] of the Library of Congress and we started to realize the value of crisp and clear digital imaging. They still have those on display today, which I’m very happy about… The building is just gorgeous.

You photograph a lot of buildings and places, but you also photograph a lot of people. You mentioned that the people of Alabama, for example, can use your photographs. Can you talk about some of the people you’ve met and as well as interesting uses of your photographs?

I’m a little untethered to it because I get a lot of requests for photos via email, and I’m glad for that. I’m happy to let people use them. My images have been used for television (like House of Cards) and in all sorts of other places. These images can be used as long as they credit me, that’s fine, or if they don’t charge because I’m not charging and the Library of Congress doesn’t charge.

I have met a tremendous amount of people, as you can imagine, particularly in small towns. Yesterday I was in Colorado, and I met a Japanese farmer who has been very successful. To learn his story was fascinating! The only state that would accept interned Japanese people was Colorado, and he started farming, and he’s been tremendously successful. I was thrilled to photograph him… It is really the small towns that give me the thrill, I must admit. I photograph people all the time because I realized that if I was just doing architecture, that would be a shame because there are people who live in those buildings and they use those buildings.

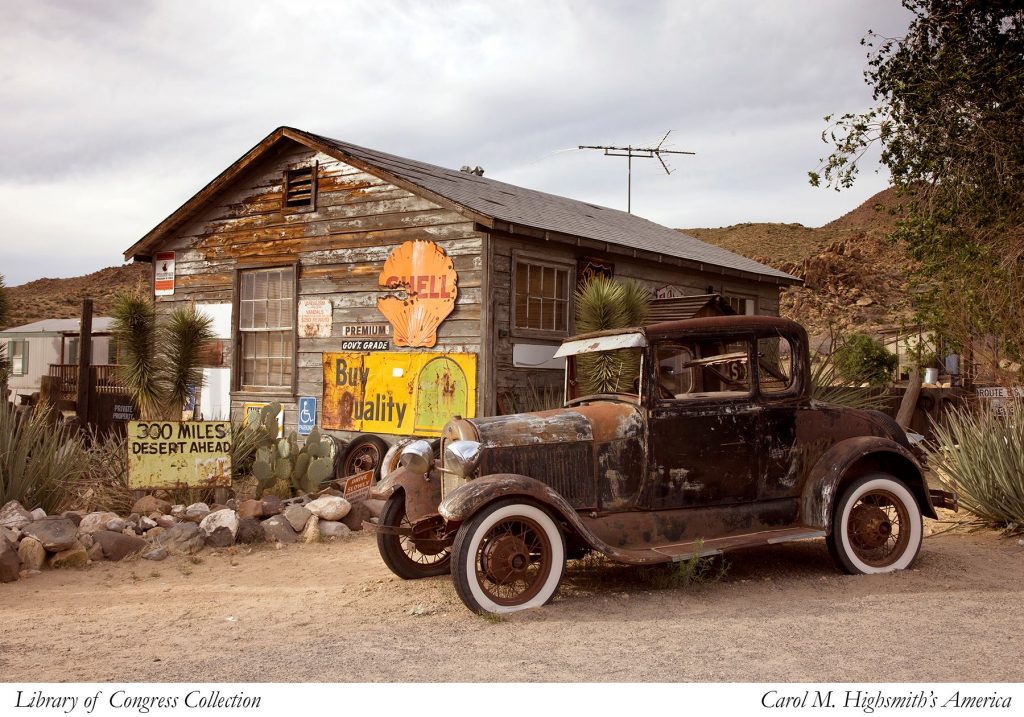

Roadside America remains a particular focus for you. What have you seen that has changed in the past few years in these small towns and on the roadside?

In 1984 I started really traveling seriously and I’ve been in towns where they just whizz by and the rotary sign is hanging from a thread, which makes me sad…

Two lane highways, or what I call disappearing America, like wooden barns, are falling apart and disappearing, but time marches on. This is my time and I’m recording it.

Across America I have seen that a lot of towns are starting to realize the importance of historic architecture. So yes, some of America is worse, but a lot of America is better. Some of the small towns are hanging by a thread, but many others have picked themselves up and moved on. There’s a lot of suffering towns with closed stores, but a lot of other towns that have reinvented themselves by fixing the stores and making them different, bringing people back downtown… I’ve been in towns where they’ve lost a lot, but there’s a lot of innovation going on around the country—it’s just so thrilling to me because I record everything. For young people to move into these places, it’s fabulous.

So you’re seeing a Renaissance of downtown, you’re saying?

I really have, yes. Where downtowns were kind of passe and people would go to the suburbs, a lot of downtowns have changed, and it’s where you want to go! It’s where the good food and movies and theaters have been restored. It’s fascinating and wonderful that it’s where people congregate.

What kinds of spaces do you take the most inspiration from?

I’m in an industry that’s kind of common – photography – and at that point America was kind of common… Well, I thought it was fascinating and I can’t really say that I just like certain parts.

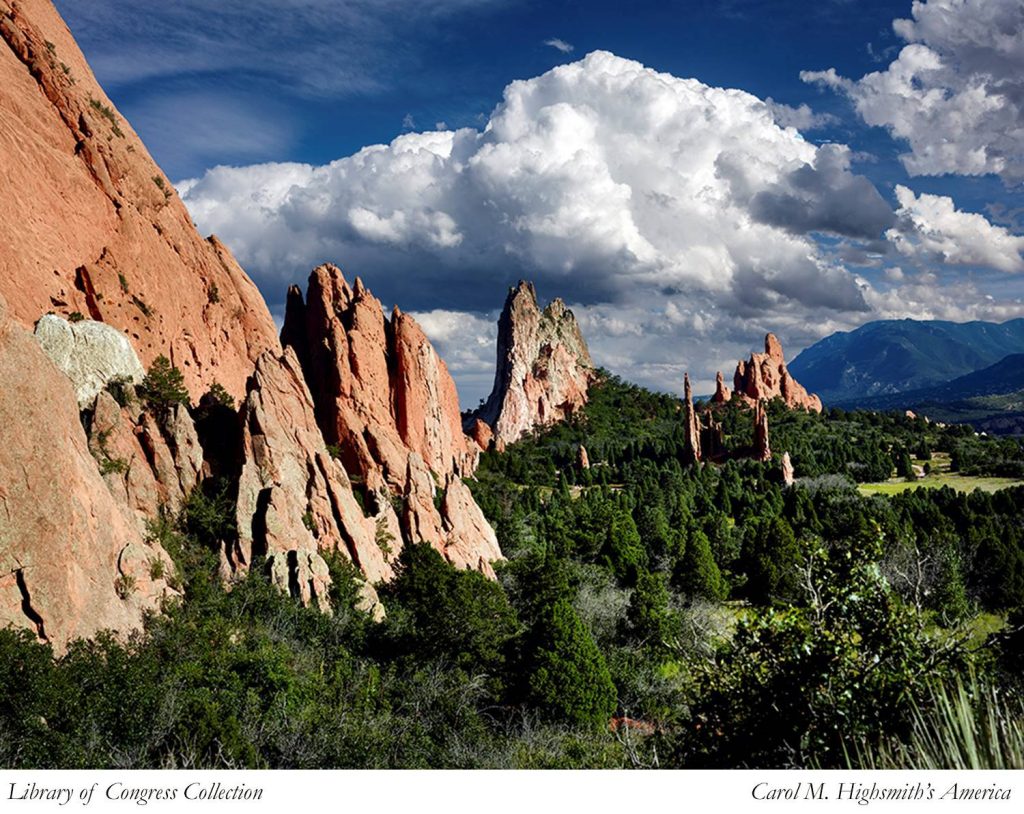

I have just finished Colorado and Wyoming, to die for states… and I’m on my way to the midwest– Iowa, Indiana, Wisconsin, Ohio. It will all be different– I may not look out and see mountains of magnitude, but I’ll look out and see other spaces that will be fascinating because America is fascinating. It’s a little bit of an out of body experience for me because I sometimes don’t realize how important my collection is in the sense that it’s showcasing our country. When I’m out doing it, I’m just out doing it!

I just love this country and I love all of it. As gorgeous as Colorado and Wyoming are, I could stand in a cornfield in Iowa on a clear day and just love it because it’s all part of who we are. I can meet just as many fascinating people as I can in Iowa as I can cowboys and cowgirls in Colorado or Wyoming. We’re all Americans, and we’re fascinating. It’s a fascinating country, so I don’t have a favorite, I’m just moved by it all. I’ll have been out in America ten months this year, which is more than we’ve been home, but it’s just that important to me to capture it.

My last question has to do with gratitude and sharing. At Creative Commons, one of our focuses is on how a culture of gratitude and sharing is “essential to a more equitable and accessible world.” How does gratitude move you to do your work, and how have you instilled a sense of gratitude in your photography?

There are a lot of very, very good images online, but if we show our cornfields and make them shine, people are going think we’re pretty special, and we are–that’s the whole point. So if I can share this and go into a small town and share these images of their town, then they can use them too. This is how it comes around and goes around as well.

When I was in Trinidad, CO this week, for instance, they went out of their way to welcome me and to show me things, and now they can have those images and use them and people around the world can see what Colorado looks like. Colorado not just the purple mountain majesty, it’s also 1/3 plains! Do people know that?

By showing us, the people in the fields, the farmers, the mountain climbers, then people can really see us. They can realize that we’re all all here on earth together and that we have a lot in common.

It doesn’t make me special because I share them because it’s really not about me, it’s about them.

They’re showcased in the Library of Congress, the library of magnitude, and I don’t think there is anywhere else in the world where people can download images like this. The Library of Congress is also sharing in kind by offering this service, which is why I’m so happy to be aligned with them, to be part of their family. The towns have gone out of their way for me to show me their best–I’ve been able to capture it, come back, put metadata to it, color correct it and make sure it’s good, the way it should be, and then it goes to the Library of Congress and they do a lot of work to get it up and then it’s there for thousands of years. How can any of us lose on this? And it’s for the world to see, for the world to see what we look like–that’s wonderful.

I photographed a carousel last night that was more than 100 years old. Will that last? Will that be here 500 years from now? Will we, as time goes on, all look the same? I don’t know. It’s not for me to know. I know that I marvel at Dorothea Lange’s photographs and Frances Benjamin Johnson’s photographs and Ansel Adams. I’m in with all those collections, and I’m hoping to carry on their legacy.

What is America? It’s a million things, from small towns to rural areas to huge cities. I was very lucky (if you can call it that) to catch the World Trade Center two months before it fell. I caught it on 4×5 film from the air and it’s probably one of the most important images I’ve taken, but I really don’t know what’s important. A lot of things will change. I just know what I’ve seen in my lifetime, and I’ve been traveling America since I was a child. I’ve been traveling all my life and looking at America out of the back seat window, so it’s not an unusual thing for me, It’s like normal and I wouldn’t trade it for the world. I love what I do. I’m not tired of traveling– it’s just fascinating to me. Absolutely fascinating, no matter where I am… I really think that I will be doing this for the rest of my life. I’ve done it for so long that I think it will carry on.