In March we hosted the second Institute for Open Leadership, and in our summary of the event we mentioned that the Institute fellows would be taking turns to write about their open policy projects.

I had the privilege of participating in the second Institute for Open Leadership (IOL), held in Cape Town and hosted by Creative Commons and the Open Policy Network. The institute was attended by people from various places around the world, all with incredible projects. For the last nine years I’ve been active in the area of documentation and museum collections management. I have a Bachelor’s degree in Museology and a Master’s in Information Science. Currently I work as collection manager of Museu da Imigração de São Paulo (Immigration Museum of São Paulo). I also teach Museology at the ETEC Parque da Juventude, where I instruct classes on museums and databases.

At the Institute for Open Leadership, I came in contact with a world little known by me: the world of initiatives supporting open knowledge, open science, open education, and much more. Moreover, as a GLAM professional (“GLAM” is an acronym for “galleries, libraries, archives, and museums”), I had the opportunity to get varied feedback on my open policy proposal I had prepared for the institute. The IOL meeting was very important for me, and in a sense was a watershed moment for the project I am leading at the Immigration Museum.

Lithuanian necklace selected to be part of the exhibition, by Conrado Secassi. CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Initially, my project was focused on the following problems: what can we explore by sharing the contents of a large, rich cultural heritage collection if we do not have much information about the underlying author’s rights, rights of publicity, or personality rights? How do we begin to transform the Museu da Imigração into an institution interested in opening its collections despite these limitations?

Many professionals working in GLAM institutions constantly face problems related to intellectual property and authors’ rights in the content of their collections. We are thus led to focus on restriction rather than sharing, which deserves attention, but for which there is no simple, prompt solution. By directly addressing these questions within the scope of my project, I hoped to find advice and best practices from other related GLAM professionals. I needed to get a better answer for how to share other than “it cannot be done.”

As I met IOL participants and learned about their projects, I heard many interesting stories about how universities and other research institutions were able to establish open policies through short, medium, and long-term initiatives. I also learned that the design and implementation of successful open licensing policies will (and should) work through different stages and levels. Finally, I learned it’s crucial to start small with my project, and to work with materials that will bring benefits for the people directly involved. And this, I can now say, was the real turning point for the Museu da Imigração’s project.

Ryukyu hat selected to be part of the exhibition, by Letícia Sá. CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Instead of focusing on the thicket of IP concerns with some of the part of our collection, I revised my project to instead explore those materials that could be used and shared in a more open way. In other words, the project was redesigned to start with items from the collection which were already free from any author’s rights restrictions, and which could, for instance, be photographed by the Museu da Imigração’s current team. The museum could— as the author of photos, texts, images, and audiovisual materials about the collection—make those objects available on the web through blogs, social media, and other platforms. At the same time, the museum could establish how this content could be re-used by anybody through the adoption of Creative Commons licenses.

Upon my return to Brazil, my first major task was to educate the Museu da Imigração’s technical teams on Creative Commons, and to get buy-in with them on what should be done to adopt an open policy at our museum. My colleagues immediately agreed that we should pursue the project, and we decided that our pilot initiative would start with all of the content produced for a temporary exhibit called O Caminho das Coisas (The Way of Things).

The main reason for choosing this particular exhibition as our pilot project was the possibility of involving several professionals in the development of content and materials to be made available online under open licenses. Everybody could see—in a relatively short period of time—the impact of their work to increase the visibility of the collections and of materials produced by the teams. Another important motivation was the fact that this exhibit was the result of a joint research effort between the Museu da Imigração, migrant communities and their descendants, partner institutions, and former donors in order to obtain additional historical information about the institution’s collections.

We agreed to use Creative Commons licenses because the licenses are a clear, objective way of telling the public what can be done with the museum’s content we make available on the web. Moreover, by using Creative Commons licenses, the museum joins the great movement promoted by CC toward sharing, remix, and reuse of knowledge on a global scale.

Based on this decision, the images of objects selected for the exhibition were produced by the team, along with the exhibit’s accompanying educational materials. We also decided that the museum’s blog and its profile on Medium should be licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 from that moment on.

The platforms used for publicizing the images were Flickr (which is heavily used in Brazil by both professional and amateur photographers and institutions), Pinterest (not very popular in Brazil, although it has faithful followers), and Wikimedia Commons. As to the latter, we were happy for the valuable assistance from Rodrigo Padula, coordinator of the Brazilian Wikipedia Group on Education and Research, who helped us in loading the images and educational materials into Wikimedia Commons.

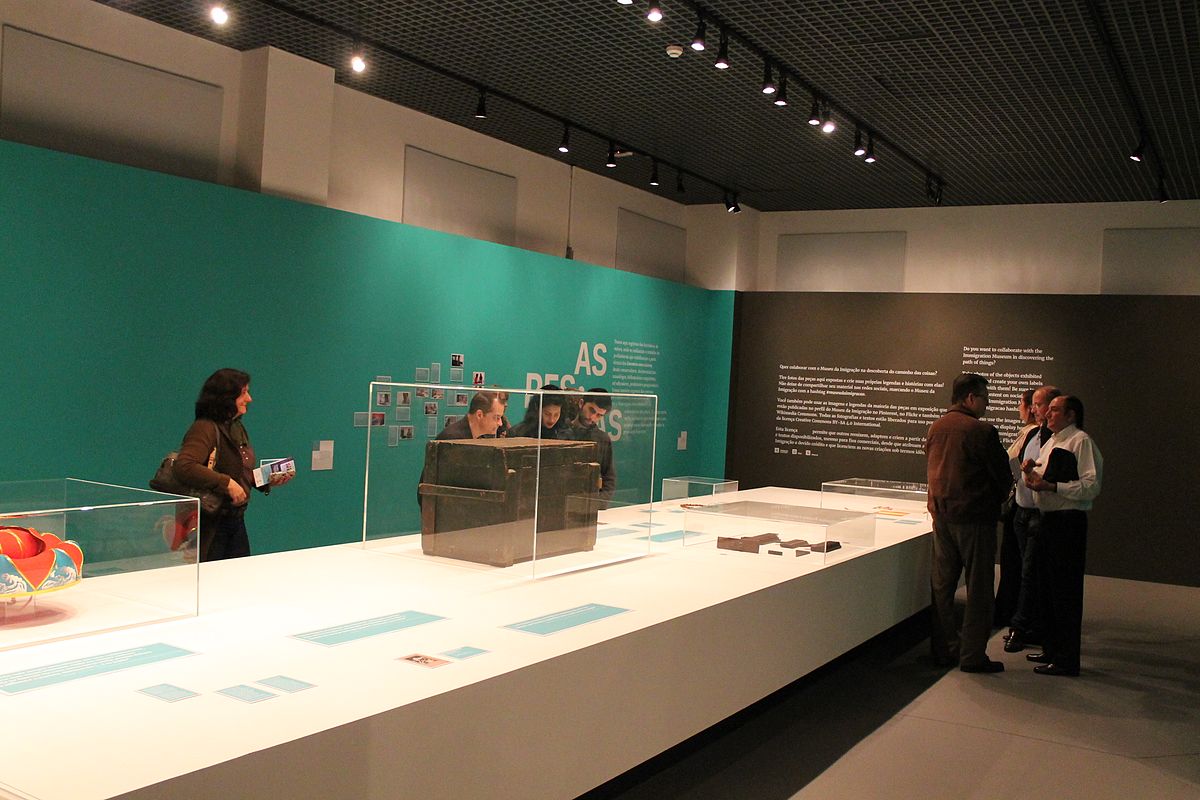

General overview of the exhibition, by Juliana Monteiro. CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

General overview of the exhibition, by Juliana Monteiro. CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

O Caminho das Coisas opened on May 21 with a beautiful design meant to stir the public into reflecting on the historical path followed by the items through the lives of their owners until they reached the museum. In addition, QR codes were posted at various locations, inviting the public to view the images in the platforms I mentioned above. We also hoped viewers would share the images and tag the museum on social media.

Our pilot project was launched nearly two months ago, and we have already gained some interesting insights. The first is that the experience has been indeed very exciting and successful. In our team’s view, the 40+ images of key items in our collection that we posted to Flickr, Pinterest, and Wikimedia Commons have opened numerous possibilities for the material’s reuse. In addition, it represents a positive step forward in making the museum’s collections more widely available to different audiences. We are also planning new initiatives by reviewing and analyzing the data and research we’ve gleaned from this pilot.

Other aspects of the exhibition have shown our team that we still have a long, productive way ahead. We identified a major challenge for GLAM institutions in Brazil is to have the capacity and knowledge to be able to consider the “openness” of all collections as a normal, everyday activity. Right now only a few of our institutions are promoting open initiatives, and the public does not always understand what can be created with these type of materials. Also, the lack of tools to encourage people to do this may be a contributing factor to this scenario. Sure, we manage to secure likes on Facebook and shares on social media, but we still don’t know if or how the images are being reused in other contexts. Finally, there is a lack of knowledge about Creative Commons licenses—both on the part of the public and by institutions as well.

With this in mind, we know it is not enough simply to upload images onto the web – we need to tell people about them, contextualize them, and get feedback and cooperation from various audiences. Our use of social media in this experience showed us that we must adapt our way of communicating about open content in order to reach new and diverse groups of people. We have already learned, for instance, that it is not worth showing photos of details of objects on Wikimedia Commons, as these types of images are not useful for illustrating Wikipedia articles. However, they can be explored on Pinterest, where the public is more accustomed to searching for these kinds of specific detailed images.

We know that Flickr is a useful tool for photographers—even those interested in licensing photos for commercial use. At the same time, we might focus on using alternative popular platforms to talk about the project and invite the public to view, enjoy, and comment on our images. Of course, apps and sites such as Instagram and Facebook are quite popular in Brazil.

We are learning by trial and error. We want to test our ideas and see which ones will mature. My IoL grant made it possible for us to include the proposal of opening our collections as something the museum should address more systematically in our internal policies and public mission. We believe that through these steps we will be positively promoting a more open cultural heritage that is increasingly accessible to all.