In April, we posed a question to our community, “How should we attribute 3D printed objects?” and announced our intent to explore the challenge as it aligned with our new strategy, focusing on discovery and collaboration. We outlined the legal questions we’d have to consider to inform our work going forward, and reached out to experts in 3D design, tech, law, and policy for an initial convening to think through these questions and help frame the challenge from a design perspective.

On June 29th, a little over twenty of us met at the Singularity University on NASA’s Ames campus in Mountain View, CA to workshop when attribution, or “view source,” matters in 3D printing, and discussed at length CC’s role in a field rich with data and designs both restricted and not restricted by copyright.

Leading up to the meeting, the original challenge we had conceived of was split into two: while participants were interested in what happened to attribution information (such as author and license) once the design was physically printed into an object, they were also interested (if not more so) in how that information traveled with the digital design file.

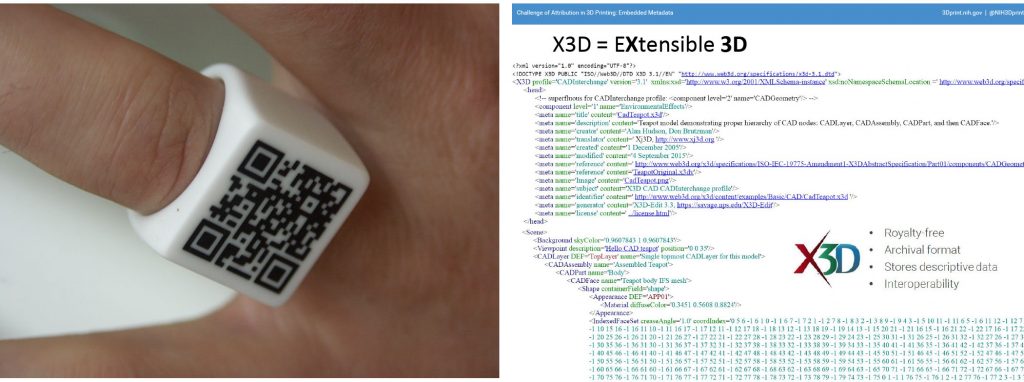

(Left: QR Code Ring detail by Individual Design, CC BY-SA / Right: X3D metadata from 3D tech slides by Meghan Coakley)

Further still, as the discussion progressed, it became apparent that the larger issue was not the physical versus digital attribution of a design, but when attribution/view source actually mattered for designers, and users of those designs, across both physical and digital spaces.

We began with a panel of designers and design community representatives who presented use cases of 3D printed designs for cultural heritage, prosthetics, military, industry, mathematical models, and more. You can check out slides from the panel here, and a video here. Following the panel we discussed and identified four overarching categories where attribution/view source mattered for designers. These are not necessarily categories of needs that CC will or should address, but they were the ones we identified as pressing needs by the 3D design community as represented at this meeting. They were:

1. The ability to track use of the design file, unmodified, including: downloads of the digital design file; the number of times the design file was sent to a printer; and geographic distribution of its uses. The motivations for being able to track use of the original design included curiosity on the part of a designer, the desire for credit, potential future revenue from uses, and compilation of such uses as part of a portfolio for professional or advocacy reasons, eg. in the case of sharing the design file of a public domain sculpture, a designer could point to the number and diversity of uses as part of a case to a cultural heritage institution to make open its 3D public domain artworks. While such tracking can bring benefits, there was also a recognition that tracking has very real costs in terms of privacy and freedom of use for downstream users.

2. The ability to compare modified versions of the design file for safety, efficacy, provenance, and productization. Safety means ensuring that printed works perform safely as expected; efficacy means ensuring that works print well in different media and perform effectively as expected; provenance means being able to track different versions of the file, including versions with different instructions for printing and also with different processes for application; and productization means being able to track when a design is productized commercially for industry.

3. The ability to indicate original intent for use of the design file, in order to prevent or preempt unwanted, unethical, or commercial uses if applicable. A strong motivation is to ensure the free use of any released design files by preventing their commercial enclosure. Unethical uses relate to safety and efficacy motivations cited in 2.

4. And last, but not least, the ability to provide credit or attribution as a normative practice, because credit provides a sort of gratification for those credited, and accountability for those who credit. Several reasons were cited for providing credit for its own sake, including: building a credible portfolio; reputation; attribution as generative for the commons (incentive for more design contributions); also as generative for growing a robust, collaborative community; for organizing multiple contributions under a single project; a source to find additional designs by the same designer; and to teach about the normative practice of attribution, eg. giving credit where credit is due, in the first place.

Keeping these four categories in mind, we moved on to the legal presentation of the applicability of copyright to 3D designs, which distinguished between functional and creative designs, and the gray space between. We discussed the lack of copyright protection for many functional designs and design files in the 3D printing space, and what that meant for CC’s role, since CC licenses and the obligation to provide attribution and source information generally apply where copyright and similar rights exist. We termed those design files that are sufficiently creative to be covered by copyright as “born closed” and those that are not as “born open.” For “born closed” design files, CC licenses enable permissions as they do for any other copyrighted work. For “born open” design files, CC licenses don’t properly apply because copyright doesn’t apply; in these cases, use of such design files is not encumbered by copyright, even if they may be controlled by other means, eg. patents, contracts or use licenses. We also discussed the lack of awareness of this distinction by most 3D designers and users and the difficulty of enabling average users to reliably draw the distinction on a case-by-case basis. And we considered the implications for designers, design communities, and CC itself of the inevitable misapplication of CC licenses to non-copyrightable designs.

(Left: Screws by andersen_mrjh, CC BY-SA / Right: Dapper Deity by Loik, CC BY-NC-SA)

We lit upon an issue that is relevant not just to 3D designers, but all kinds of creators of content generally. The group recognized that CC licenses are sometimes misapplied to works that are not restricted by copyright or similar rights. This misapplication is one that CC seeks to avoid even though their use with all types of content can result in raising awareness about CC licenses and educating users about the importance of a shared commons. One question the group explored was, how might CC be more intentional about these imperfect applications, improving awareness around how and where CC licenses should be used? Furthermore, can CC play a greater role by automating ways to give credit and enabling expressions of gratitude for contributions? Should these features be enabled just for the subset of the copyrightable 3D commons or for all 3D works where an attribution norm (as opposed to attribution as a legal requirement) is desired?

Note: CC is exploring the development of an open ledger, aggregating data from publicly available repositories of open content, possibly starting with 3D printed works. One could imagine a public listing of 3D printed works containing provenance and other relevant metadata that gets edited and curated over time, by both verified institutions and a community of users. All participating platforms could add new data, and draw on data from other projects using the ledger.

Setting these questions aside for a moment, we moved into the technical session after lunch, which included presentations on current ways attribution/view source is being included in the physical objects; potential technical solutions and the benefits/drawbacks of each; and current file standard formats that allow for attribution metadata to be included in the digital design file. You can check out these presentations here.

Due to the variety of function, size, and design of physical objects, it seems less likely that a physical standard for attribution would be universally adopted. That said, such a standard would not be impossible, at least for a subset of objects within a given field, for example, sculptural public domain art works. More likely is the adoption of a digital metadata standard to be included with the design file that would express attribution information, such as author and license. Such standard metadata could be tied to its physical expression later on, and also feed into the open ledger.

In our last hour, we revisited the question about CC’s role in the 3D commons, as related to and not related to copyright. Our renewed vision and strategy focuses on increasing discovery and enabling collaboration around the commons. Do we limit ourselves to just CC licenseable content when it comes to the commons? Or does increasing discovery and collaboration of CC licensed content necessitate increasing discovery and collaboration of all content generally? If by increasing discovery and collaboration, we want to enable automatic attribution and ways to express gratitude for contributions, how do we distinguish between contribution credit (to recognize work put into creation, but not necessarily copyright ownership) versus authorship credit (copyright ownership)? What are the dangers for encouraging attribution norms for content that is not copyrightable in the first place? Eg. do we risk expanding copyright or copyright-like restrictions to areas that were never governed by copyright in the first place? Could we navigate this space as we do other spaces, by, as a policy matter, insisting that CC licenses only apply where copyright applies, and increasing efforts to educate users about the black, white, and gray areas?

We didn’t come to any hard and fast conclusions, but we did manage to outline some next steps. They are:

1. Solicit feedback from additional stakeholders, including you, our community.

2. Pilot test a few ideas with a platform and related partners, starting with a standard attribution metadata format for the digital design file. Also identify education needs and create resources for users on when CC licensing applies to 3D designs as pertains to a specific platform, eg. Thingiverse.

3. Explore additional convenings focusing on solving for one specific challenge identified above, eg. a technical standard for metadata file formats.

4. Start talking to potential funders to see if there is an interest in these issues, especially in an open ledger, specifically for the 3D commons or more broadly for all CC licenseable works.

5. Explore the development of another tool or expression that is not a copyright license but that addresses the four categories of designer needs identified above.

We look forward to hearing your thoughts:

- When and where does attribution/view source matter to you in the 3D design space (if at all)? Do the four categories of designer needs around attribution/view source capture your own particular needs as a designer and user?

- What’s more important — being able to view the source on a printed 3D physical object or find the source information on the digital design file?

- Given copyright does not apply to many types of 3D designs, the attribution requirement of the CC licenses does not apply in those instances. CC has historically been focused primarily on copyright-related tools. Does CC still have a role to play in this space around enabling automatic types of attribution, credit, or gratitude for contributions as a community norm through the development of a specialized tool(s) or otherwise?

Lastly, what other organizations or projects should we be aware of and work with when exploring possibilities for developing collaboration mechanisms? Please provide any feedback in this form.