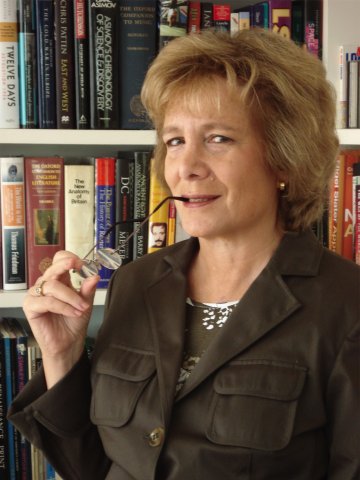

Recently, we had a chance to speak with Frances Pinter, Publisher of Bloomsbury Academic, a new imprint launched by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc last month. Frances has been in the publishing industry since she was 23, when she started her own academic publishing house, Pinter Publishers. She comes to Bloomsbury Academic as the former Publishing Director of the Soros Foundation, where she “directed major projects aimed at reforming publishing in Central & Eastern Europe,” “pioneered ventures offering libraries affordable digital access to thousands of learned journals,” and “enabled the digital publication of a major Russian encyclopedia.”

The new publishing model consists of releasing works for free online through a Creative Commons or other open license, and then offering print-on-demand (POD) copies at reasonable prices. The University of Michigan’s Espresso Book Machine adheres to this model at $10 per public domain book, as does Flatworld Knowledge and Lulu.com. Bloomsbury Plc, a leading European publisher housing works such as Harry Potter, takes a similar step with Bloomsbury Academic, which will publish works in the Humanities and Social Sciences exclusively under non-commercial CC licenses. Their first title, Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy, will be available for download soon, and is authored by our very own Lawrence Lessig, board member and former CEO of Creative Commons.

In a follow-up conversation over email, I asked Frances questions that cropped up during a phone call with our Executive Director, Ahrash Bissell, some eight time zones apart (from San Francisco to London). Her responses are below.

You have a lot of experience in publishing, having started your own academic publishing house, Pinter Publishers, at the age of 23. You’re also coming from the Soros Foundation, which supports open society activities. How did your prior experiences lead you to your current role as publisher for Bloomsbury Academic? Was there something specific about your first publishing enterprise that inspired your current commitment to publishing reform and the open book model?

At Pinter Publishers I was always interested in what was new coming out of the social sciences. One list that we pioneered thirty years ago was around the social and economic implications of new technology. Now all and more (and in some cases less) than what was predicted then has, or is, coming true. Working in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union while at the Soros Foundation gave me an insight into how stultifying closed societies were, and how important it is to level the playing field when it comes to access to knowledge. Now I’m in a position to make a contribution to taking forward some of the new business approaches in the digital age and improve access to knowledge. It is a thrilling opportunity.

Can you say a few words about Bloomsbury Academic and how it’s a departure from the Bloomsbury Publishing model? What prompted the folks at Bloomsbury to develop this new initiative?

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc is a wonderful company full of the best of traditional publishing values. Now that they’ve been so successful with Harry Potter, they are looking to diversify and specialize, and academic publishing has become a priority. Of course, the idea of putting the complete content of a book online is still seen as radical by many in the publishing industry. However, the Bloomsbury people took a look beyond the horizon and could see that something other than the traditional business models needed to be tested. I brought them the idea of allowing content to be online through a Creative Commons Attribution, Non-commercial license (CC BY-NC), with enough early evidence that this would work. We’ll now see whether it [works] on a larger scale and within the confines of a company that must stay commercial to survive.

Our business model is simple. We may lose some print sales because of free access, but we will gain other sales because more people will want the print edition. Librarians know that most people do not want to read a 300 page book on screen and that once you have more than two or three people printing out a book in a university, it is cheaper to just buy a copy for the library – and it is much more environmentally friendly. We will also have flexibility on how we produce the printed copies – whether through traditional printing methods or print on demand (POD). We hope to show that digital and print [copies] can co-exist for certain types of publications for some time to come, and be financially sustainable.

On your website, Bloomsbury Academic is described as “employing the latest solutions in digital publishing.” What problems are the solutions addressing? In other words, what are the current challenges in publishing? How is Bloomsbury Academic hoping to overcome these challenges? And more specifically, what are the latest solutions being employed?

We are still working on our platform, and it will be some time before it is fully operational. However, for academic material the metadata is crucial. Search, interoperability are all key factors. Yet, how to set something up in this transition period that will be flexible enough to adapt while standards are settling down is the key challenge.

Why did Bloomsbury Academic choose Creative Commons licensing, as opposed to other open content licensing, for its new imprint? How do you think Bloomsbury Academic’s goals are similar to Creative Commons’?

Creative Commons is the best known license for this kind of publishing. There are still some issues with it, such as defining very precisely what is ‘commercial’. However, we felt that on balance it was best to go with a license that had such wide recognition. One reason for putting the whole text online free of charge is to avoid all the fuss and confusion that arises when publishers allow odd excerpts online and free downloads for limited periods etc. This may be good PR, but better to have a policy that is more focused on delivering what authors and readers want – which is to use the Web as a library. This is especially true of academic works.

In the early 2000s battle lines were drawn between publishers who sought refuge behind copyright laws and academics who were pushing for open access. I thought this was unfortunate because too much energy was spent hurling abuse across the trenches. I think much has changed recently and both sides realise that a) the added value that the publishing process brings is desirable b) this costs money whether done inside a publishing house or outside of it and c) that by working out some new models together we might just get to where we need to be more quickly than otherwise. I’m getting lots of cooperation from all sides and actually everyone wants our business model to work.

I have heard that you are spearheading pilot projects testing “the viability of CC licensing” in South Africa and Uganda. How is that going?

PALM – Africa is a project funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) of Canada. PALM stands for Publishing and Alternative Licensing Models. We were aiming to introduce open content licensing and its benefits to a wide range of publishers. There were a few precedents, indeed, the HSRC Press in Cape Town has been a lone pioneer in this area for a few years now. And New Vision, a Ugandan newspaper saw their sales double when they put their content online free of charge – though they hadn’t actually licensed it. Now they are fans of Creative Commons.. So far the interest by commercial and non-commercial publishers has greatly exceeded our expectations. There is still another year to go with the PALM Project, but your readers can find out more from http://www.idrc.ca/acacia/ev-117012-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html

Interoperability is a major issue when it comes to open content licensing, especially in education as educators and researchers are looking not only to access materials, but to be able to remix, reformat, and redistribute the materials so that they are effective within diverse cultural, individual and institutional contexts. What are your thoughts on this? How does Bloomsbury Academic plan to address the issue of interoperability?

Interoperability on a technical level is important. The extent to which authors want to allow remix and reformatting is something we will encourage but I can see that in certain instances this may not be what an author wants. Our approach will be to let authors have the option to choose the no derivatives option if they wish, but I hope this won’t be needed in most cases.

Lastly, what can we expect from Bloomsbury Academic in the future?

Firstly, you can expect something right away, at least in some parts of the world. We are publishing this month the book REMIX: Making Art and Culture Thrive in the Hybrid Economy, by Lawrence Lessig. I have to say, this is not the typical type of book for Bloomsbury Academic – but it does illustrate the strength of the company behind me. Larry had already signed a contract with Penguin Press for the USA and Canada. His agent was about to start selling the UK and Commonwealth rights this autumn. The book was offered to me even though we only opened our doors on September the 5th. I grabbed it and we put it through the so called ‘trade’ channels of Bloomsbury, meaning that we could publish in paperback and were able to get it stocked in bookstores. Penguin and Bloomsbury will be competing with one another in the rest of the world – which we in publishing refer to as an ‘open market’. Our edition is less expensive – so I hope good old market forces will be on our side!

However, most of our books will be scholarly books for the academic market and our core sales will be to libraries, though I hope individual scholars and students will also purchase our books when they want a break from reading on screen. I am in the process of hiring staff and setting up systems, and the first titles in the social sciences and humanities can be expected some time in 2009.

I’m planning a number of series that cut across subject areas that are relevant in today’s world. For instance I’d like to publish a series on access to knowledge that covers all aspects of intellectual property rights and how they impact access to medicine, arts and culture, access to knowledge and the coming vexed issues around nanotechnology. I think there is a lot of fundamental social research that can help explain the unease people are feeling about the way our world is going. And, of course, we will feature development studies. It is important for developing countries to share their research with the rest of the world and for audiences that do not have access to printed materials to be able to access research that has policy implications for them.

For more about Frances’ view of the new publishing model, see her presentation–“The Transformation of Academic Publishing in the Digital Era“–given at the Oxford Internet Institute.