Jehovah

Did you know...

Arranging a Wikipedia selection for schools in the developing world without internet was an initiative by SOS Children. Sponsoring children helps children in the developing world to learn too.

Jehovah (pronounced /dʒɨˈhoʊvə/) is an anglicized representation of Hebrew יְהֹוָה, a vocalization of the Tetragrammaton יהוה (YHWH), the proper name of the God of Israel in the Hebrew Bible.

יְהֹוָה appears 6,518 times in the traditional Masoretic Text, in addition to 305 instances of יֱהֹוִה (Jehovih). The earliest available Latin text to use a vocalization similar to Jehovah dates from the 13th century.

Most scholars believe "Jehovah" to be a late (ca. 1100 CE) hybrid form derived by combining the Latin letters JHVH with the vowels of Adonai, but there is some evidence that it may already have been in use in Late Antiquity (5th century). It was certainly not the historical vocalization of the Tetragrammaton at the time of the redaction of the Pentateuch (6th century BCE), at which time the most likely vocalization was Yahweh. The historical vocalization was lost because in Second Temple Judaism, during the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE, the pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton came to be avoided, being substituted with Adonai "my Lords".

Pronunciation

Most scholars believe "Jehovah" to be a late (ca. 1100 CE) hybrid form derived by combining the Latin letters JHVH with the vowels of Adonai, but there appears to be evidence that Jehovah form of the Tetragrammaton may have been in use in Semitic and Greek phonetic texts and artifacts from Late Antiquity. Others say that it is the pronunciation Yahweh that is testified in both Christian and pagan texts of the early Christian era.

Some proponents of the rendering Jehovah, including Karaite Jews, state that although the original pronunciation of יהוה has been obscured by disuse of the spoken name according to oral Rabbinic law, well-established English transliterations of other Hebrew personal names are accepted in normal usage, such as Joshua, Isaiah or Jesus, for which the original pronunciations may be unknown. Some argue that Jehovah is preferable to Yahweh, based on their conclusion that the Tetragrammaton was likely tri-syllabic originally, and that modern forms should therefore also have three syllables.

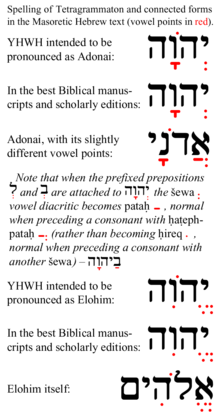

According to a Jewish tradition developed during the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE, the Tetragrammaton is written but not pronounced. When read, substitute terms replace the divine name where יְהֹוָה appears in the text. It is widely assumed, as proposed by the 19th-century Hebrew scholar Gesenius, that the vowels of the substitutes of the name—Adonai (Lord) and Elohim (God)—were inserted by the Masoretes to indicate that these substitutes were to be used. When יהוה precedes or follows Adonai, the Masoretes placed the vowel points of Elohim into the Tetragrammaton, producing a different vocalization of the Tetragrammaton יֱהֹוִה, which was read as Elohim. Based on this reasoning, the form יְהֹוָה (Jehovah) has been characterized as a "hybrid form", and even "a philological impossibility".

Early modern translators disregarded the practice of reading Adonai (or its equivalents in Greek and Latin) in place of the Tetragrammaton and instead combined the four Hebrew letters of the text with the vowel points that, except in synagogue scrolls, accompanied them, resulting in the form Jehovah. This form, already in use by Roman Catholic authors such as Ramón Martí, achieved wide use in the translations of the Protestant Reformation. In the 1611 King James Version, Jehovah occurred seven times. In the 1901 American Standard Version, it was still the regular English rendition of יהוה, in preference to "the LORD". It is also used in Christian hymns such as the 1771 hymn, "Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah".

Development

The most widespread theory is that the Hebrew term יְהֹוָה has the vowel points of אֲדֹנָי (adonai). Using the vowels of adonai, the composite hataf patah ֲ under the guttural alef א becomes a sheva ְ under the yod י, the holam ֹ is placed over the first he ה, and the qamats ָ is placed under the vav ו, giving יְהֹוָה (Jehovah). When the two names, יהוה and אדני, occur together, the former is pointed with a hataf segol ֱ under the yod י and a hiriq ִ under the second he ה, giving יֱהֹוִה, to indicate that it is to be read as (elohim) in order to avoid adonai being repeated.

The pronunciation Jehovah is believed to have arisen through the introduction of vowels of the qere—the marginal notation used by the Masoretes. In places where the consonants of the text to be read (the qere) differed from the consonants of the written text (the kethib), they wrote the qere in the margin to indicate the desired reading. In such cases, the kethib was read using the vowels of the qere. For a few very frequent words the marginal note was omitted, referred to as q're perpetuum. One of these frequent cases was God's name, which was not to be pronounced in fear of profaning the "ineffable name". Instead, wherever יהוה (YHWH) appears in the kethib of the biblical and liturgical books, it was to be read as אֲדֹנָי (adonai, "My Lord [plural of majesty]"), or as אֱלֹהִים (elohim, "God") if adonai appears next to it. This combination produces יְהֹוָה (yehovah) and יֱהֹוִה (yehovih) respectively. יהוה is also written ’ה, or even ’ד, and read ha-Shem ("the name").

Scholars are not in total agreement as to why יְהֹוָה does not have precisely the same vowel points as adonai. The use of the composite hataf segol ֱ in cases where the name is to be read, "elohim", has led to the opinion that the composite hataf patah ֲ ought to have been used to indicate the reading, "adonai". It has been argued conversely that the disuse of the patah is consistent with the Babylonian system, in which the composite is uncommon.

Vowel points of יְהֹוָה and אֲדֹנָי

The table below shows the vowel points of Yehovah and Adonay, indicating the simple sheva in Yehovah in contrast to the hataf patah in Adonay. As indicated to the right, the vowel points used when YHWH is intended to be pronounced as Adonai are slightly different to those used in Adonai itself.

| Hebrew ( Strong's #3068) YEHOVAH יְהֹוָה |

Hebrew (Strong's #136) ADONAY אֲדֹנָי |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| י | Yod | Y | א | Aleph | glottal stop |

| ְ | Simple sheva | E | ֲ | Hataf patah | A |

| ה | He | H | ד | Dalet | D |

| ֹ | Holam | O | ֹ | Holam | O |

| ו | Vav | V | נ | Nun | N |

| ָ | Qamats | A | ָ | Qamats | A |

| ה | He | H | י | Yod | Y |

The difference between the vowel points of ’ǎdônây and YHWH is explained by the rules of Hebrew morphology and phonetics. Sheva and hataf-patah were allophones of the same phoneme used in different situations: hataf-patah on glottal consonants including aleph (such as the first letter in Adonai), and simple sheva on other consonants (such as the Y in YHWH).

Introduction into English

The Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon suggested that the pronunciation Jehovah was unknown until 1520 when it was introduced by Galatinus, who defended its use. However, it has been found as early as about 1270 in the Pugio fidei of Raymund Martin.

In English it appeared in William Tyndale's translation of the Pentateuch ("The Five Books of Moses"), published in 1530 in Germany, where Tyndale had studied since 1524, possibly in one or more of the universities at Wittenberg, Worms and Marburg, where Hebrew was taught. The spelling used by Tyndale was "Iehouah"; at that time, I was not distinguished from J, and U was not distinguished from V. The original 1611 printing of the Authorized King James Version used "Iehovah". Tyndale wrote about the divine name: "IEHOUAH [Jehovah], is God's name; neither is any creature so called; and it is as much to say as, One that is of himself, and dependeth of nothing. Moreover, as oft as thou seest LORD in great letters (except there be any error in the printing), it is in Hebrew Iehouah, Thou that art; or, He that is."

The name Jehovah appeared in all early Protestant Bibles in English, except Coverdale's translation in 1535. The Roman Catholic Douay-Rheims Bible used "the Lord", corresponding to the Latin Vulgate's use of "Dominus" (Latin for "Adonai", "Lord") to represent the Tetragrammaton. The Authorized King James Bible also, which used Jehovah in a few places, most frequently gave "the LORD" as the equivalent of the Tetragammaton. The name Jehovah appeared in John Rogers' Matthew Bible in 1537, the Great Bible of 1539, the Geneva Bible of 1560, Bishop's Bible of 1568 and the King James Version of 1611. More recently, it has been used in the Revised Version of 1885, the American Standard Version in 1901, and the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures of the Jehovah's Witnesses in 1961.

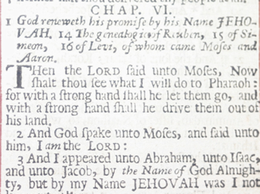

At Exodus 6:3-6, where the King James Version has Jehovah, the Revised Standard Version (1952), the New American Standard Bible (1971), the New International Version (1978), the New King James Version (1982), the New Revised Standard Version (1989), the New Century Version (1991), and the Contemporary English Version (1995) give "LORD" or "Lord" as their rendering of the Tetragrammaton, while the New Jerusalem Bible (1985), the Amplified Bible (1987), the New Living Translation (1996, revised 2007), the English Standard Version (2001), and the Holman Christian Standard Bible (2004) use the form Yahweh.

Hebrew vowel points

Modern guides to biblical Hebrew grammar, such as Duane A Garrett's A Modern Grammar for Classical Hebrew state that the Hebrew vowel points now found in printed Hebrew Bibles were invented in the second half of the first millennium AD, long after the texts were written. This is indicated in the authoritative Hebrew Grammar of Gesenius, and in encyclopedias such as the Jewish Encyclopedia, the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and Godwin's Cabalistic Encyclopedia, and is acknowledged even by those who claim that guides to Hebrew are perpetuating "scholarly myths".

"Jehovist" scholars, who believe pronounced /dʒəˈhoʊvə/ to be the original pronunciation of the divine name, argue that the Hebraic vowel-points and accents were known to writers of the scriptures in antiquity and that both Scripture and history argue in favour of their ab origine status to the Hebrew language. Some members of Karaite Judaism, such as Nehemia Gordon, hold this view. The antiquity of the vowel points and of the rendering Jehovah was defended by various scholars, including Michaelis, Drach, Stier, William Fulke (1583), Johannes Buxtorf, his son Johannes Buxtorf II, and John Owen (17th century); Peter Whitfield and John Gill (18th century); John Moncrieff (19th century); and more recently by Thomas D. Ross, G. A. Riplinger, John Hinton, and Thomas M. Strouse (21st century).

Jehovist writers such as Nehemia Gordon, who helped translate the "Dead Sea Scrolls", have acknowledged the general agreement among scholars that the original pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton was Yahweh, and that the vowel points now attached to the Tetragrammaton were added to indicate that Adonai was to be read instead, as seen in the alteration of those points after prefixes. He wrote: "There is a virtual scholarly consensus concerning this name" and "this is presented as fact in every introduction to Biblical Hebrew and every scholarly discussion of the name." Gordon, disputing this consensus, wrote, "We have seen that the scholarly consensus concerning Yahweh is really just a wild guess," and went on to say that the vowel points of Adonai are not correct. He argued that "the name is really pronounced Ye-ho-vah with the emphasis on 'vah'. Pronouncing the name Yehovah with the emphasis on 'ho' (as in English Jehovah) would quite simply be a mistake."

Proponents of pre-Christian origin

18th-century theologian John Gill puts forward the arguments of 17th-century Johannes Buxtorf II and others in his writing, A Dissertation Concerning the Antiquity of the Hebrew Language, Letters, Vowel-Points and Accents. He argued for an extreme antiquity of their use, rejecting the idea that the vowel points were invented by the Masoretes. Gill presented writings, including passages of scripture, that he interpreted as supportive of his "Jehovist" viewpoint that the Old Testament must have included vowel-points and accents. He claimed that the use of Hebrew vowel points of יְהֹוָה, and therefore of the name Jehovah (pronounced /jəˈhoʊvə/), is documented from before 200 BCE, and even back to Adam, citing Jewish tradition that Hebrew was the first language. He argued that throughout this history the Masoretes did not invent the vowel points and accents, but that they were delivered to Moses by God at Sinai, citing Karaite authorities Mordechai ben Nisan Kukizov (1699) and his associates, who stated that "all our wise men with one mouth affirm and profess that the whole law was pointed and accented, as it came out of the hands of Moses, the man of God." The argument between Karaite and Rabbinic Judaism on whether it was lawful to pronounce the name represented by the Tetragrammaton is claimed to show that some copies have always been pointed (voweled) and that some copies were not pointed with the vowels because of " oral law", for control of interpretation by some Judeo sects, including non-pointed copies in synagogues. Gill claimed that the pronunciation pronounced /jəˈhoʊvə/ can be traced back to early historical sources which indicate that vowel points and/or accents were used in their time. Sources Gill claimed supported his view include:

- The Book of Cosri and commentator Rabbi Judab Muscatus, which claim that the vowel points were taught to Adam by God.

- Saadiah Gaon (927 AD)

- Jerome (380 AD)

- Origen (250 AD)

- The Zohar (120 AD)

- Jesus Christ (31 AD), based on Gill's interpretation of Matthew 5:18

- Hillel the Elder and Shammai division (30 BC)

- Karaites(120 BCE)

- Demetrius Phalereus, librarian for Ptolemy II Philadelphus king of Egypt (277 BCE)

Gill quoted Elia Levita, who said, "There is no syllable without a point, and there is no word without an accent," as showing that the vowel points and the accents found in printed Hebrew Bibles have a dependence on each other, and so Gill attributed the same antiquity to the accents as to the vowel points. Gill acknowledged that Levita, "first asserted the vowel points were invented by " the men of Tiberias", but made reference to his condition that "if anyone could convince him that his opinion was contrary to the book of Zohar, he should be content to have it rejected." Gill then alludes to the book of Zohar, stating that rabbis declared it older than the Masoretes, and that it attests to the vowel-points and accents.

William Fulke, John Gill, John Owen, and others held that Jesus Christ referred to a Hebrew vowel point or accent at Matthew 5:18, indicated in the King James Version by the word tittle. Fulke argued that the words of this verse, spoken in Hebrew, but transliterated into Greek in the New testament, are proof that these marks were applied to the Torah at that time. John Lightfoot (1602–1675) claimed the Hebrew vowel points were of the Holy Spirit's invention, not of the Tiberians', characterizing the latter as "lost, blinded, besotted men."

In Peter Whitfield's A Dissertation on the Hebrew Vowel-Points, the author examined the positions of Levita and Capellus, giving many biblical examples to refute their notion of the novelty of vowel points. In his introduction, he claimed that the Roman Catholic Church favored Levita's position because it allowed the priests to have the final say in interpretation. The lack of authoritative vowel points in the Hebrew Old Testament, he said, leaves the meaning of many words to the interpreter. Citing the meaning of the Hebrew word for "Masoretes"—māsar, which means "to hand over", "to transmit"—, Whitfield gave 10 reasons for holding that the Hebrew vowel points and accents have to be used for Hebrew to be "clearly understood":

- I. The necessity of vowel-points in reading the Hebrew language (pp. 6–46). Without vowels, he said, simple pronunciations so necessary in learning a language are impossible. He reproved as naiveté Levita's suggestion that the master could teach a child with a thrice-rehearsed effort (pp. 22–23). He gave several biblical examples as proving this necessity.

- II. The necessity for forming different Hebrew conjugations, moods, tenses, as well as dual and plural endings of nouns (pp. 47–57). That both Hebrew verbs, including the seven conjugations, the moods and tenses, and the Hebrew nouns, with singular, dual and plural endings, are based on vowel diagnostic indicators is, he claimed, without controversy. The tremendous complexity of the Hebrew language without vowels argues against any oral tradition preservation inscripturated through the recent invention of vowels. Whitfield argued: "Whoever will consider a great many instances of these differences, as they occur, will own, he must have been a person of very great sagacity, who could ever have observed them without the points" (p. 48).

- III. The necessity of vowel-points in distinguishing a great number of words with different significations which without vowel-points are the same (58-61). Whitfield gave many examples of the same consonants with different points constituting different words. The diacritical mark (dot) above the right tooth or the left tooth of the shin/sin letter makes a great difference in some words. He said that if he gave all the examples, he would need "to transcribe a good part of the Bible or lexicon" (p. 58).

- IV. The inconsistency of the lateness of vowel-points in light of the Jew's zeal for their language since the Babylonian captivity (62-65). The Jews were zealous for their language, Whitfield observed, and they would not have been careless to let the inscripturated vocalization disappear through careless or indifferent oral tradition from the time of the captivity onward. He cited several ancient authorities describing the Jews' fanaticism about protecting the minuteness of their Scripture.

- V. The various and inconsistent opinions of the advocates for the novelty of vowel-points concerning the authors, time, place, and circumstances of their institution (66-71). Whitfield argued that the advocates for the recent vowel system had a wide variety of suggestions. Concerning the authors, some maintained that the inventor[s] were the Tiberian Jews while others suggested that it was Rabbi Judah Hakkadosh (c. AD 230). Some said the points were invented after the Talmud (c. AD 200-500), by the Masoretes (AD 600), or in the 10th or the 11th century. For the place some had posited Tiberias whereas others had suggested the Asia Minor.

- VI. The total silence of the ancient writers, Jew and Christian, about their recent origin (72-88). Whitfield cited both early rabbins and Jerome as neglecting to refer to the late (post-Mosaic) origin of vowel-points.

- VII. The absolute necessity to ascertain Divine authority of the Scripture of the OT (89-119). Whitfield affirmed that Scripture is based on words and words are based on consonants and vowels. If there are no vowels in the Hebrew OT originals, then there is no Divine authority of the Hebrew OT Scriptures, he argued, citing 2 Tim. 3:16. He then gave a vast listing of passages that change meaning when points are lost, and thereby undermining divine authority.

- VIII. The many anomalies or irregularities of punctuation in the Hebrew grammar (120-133). This objection by Whitfield to the novelty of vowel-points was the many exceptions to vowel-point rules, anomalies and irregularities that demand a codified system for their exceptions to emphasize a particular point of grammar and truth.

- IX. The importance of the Kethiv readings versus the Keri marginal renderings (134-221). The existence of Kethiv (Aramaic for "write") readings in the Hebrew text and Keri (Aramaic for "call") readings in the margin of Hebrew manuscripts showed, he said, that the rabbins were serious about preserving the original words, including the vowel-points, when a questionable word arose in a manuscript. The pre-Christian antiquity of the Keri readings in the margin demanded the pre-Masoretic antiquity of the vowel points.

- X. The answer to two material questions (222-282). Whitfield responded to two of three significant questions in this section: 1) why does the LXX and Jerome's version differ from the Hebrew text in corresponding vowels on proper names? 2) Why the silence of the Jewish writers on the pointing prior to the 6th century of Christianity? and 3) Why were unpointed copies used in the Jewish synagogues? Briefly, he responded to the first questions by stating that the differences in the translations and the Hebrew pointed texts cannot be attributed to the vowels, since he said that the translators obviously did use the pointed copies, and that the Jewish commentators, coeval with the Masoretes, did in fact refer to the points. The third question, answered later in his book, was responded to by saying that there is no historical proof that unpointed copies were used exclusively in the synagogues.

The 1602 Spanish Bible ( Reina-Valera/ Cipriano de Valera) used the name Iehova and gave a lengthy defense of the pronunciation Jehovah in its preface.

In Thomas D. Ross' book, The Battle over the Hebrew Vowel Points, Examined Particularly As Waged in England, he presents the various points of view regarding the Hebrew Vowel-Points down to the 19th century. He states that the overwhelming majority of present-day Hebrew scholarship believes that the vowel points were added by the Masoretes, but notes that some sections of fundamentalism still hold that they were part of the original text.

Proponents of later origin

Despite Jehovist claims that vowel signs are necessary for reading and understanding Hebrew, modern Hebrew is written without vowel points. The Torah scrolls do not include vowel points, and ancient Hebrew was written without vowel signs.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in 1946 and dated from 400 BC to 70 AD, include texts from the Torah or Pentateuch and from other parts of the Hebrew Bible, and have provided documentary evidence that, in spite of claims to the contrary, the original Hebrew texts were in fact written without vowel points. Menahem Mansoor's The Dead Sea Scrolls: A College Textbook and a Study Guide claims the vowel points found in printed Hebrew Bibles were devised in the 9th and 10th centuries.

Gill's view that the Hebrew vowel points were in use at the time of Ezra or even since the origin of the Hebrew language is stated in an early 19th-century study in opposition to "the opinion of most learned men in modern times", according to whom the vowel points had been "invented since the time of Christ". The study presented the following considerations:

- The argument that vowel points are necessary for learning to read Hebrew is refuted by the fact that the Samaritan text of the Bible is read without them and that several other Semitic languages, kindred to Hebrew, are written without any indications of the vowels.

- The books used in synagogue worship have always been without vowel points, which, unlike the letters, have thus never been treated as sacred.

- The Qere Kethib marginal notes give variant readings only of the letters, never of the points, an indication either that these were added later or that, if they already existed, they were seen as not so important.

- The Kabbalists drew their mysteries only from the letters and completely disregarded the points, if there were any.

- In several cases, ancient translations from the Hebrew Bible ( Septuagint, Targum, Aquila of Sinope, Symmachus, Theodotion, Jerome) read the letters with vowels different from those indicated by the points, an indication that the texts from which they were translating were without points. The same holds for Origen's transliteration of the Hebrew text into Greek letters. Jerome expressly speaks of a word in Habakkuk 3:5, which in the present Masoretic Text has three consonant letters and two vowel points, as being of three letters and no vowel whatever.

- Neither the Jerusalem Talmud nor the Babylonian Talmud (in all their recounting of Rabbinical disputes about the meaning of words), nor Philo nor Josephus, nor any Christian writer for several centuries after Christ make any reference to vowel points.

Early modern arguments

In the 16th and 17th centuries, various arguments were presented for and against the transcription of the form Jehovah.

Discourses rejecting Jehovah

| Author | Discourse | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| John Drusius (Johannes Van den Driesche) (1550-1616) | Tetragrammaton, sive de Nomine Die proprio, quod Tetragrammaton vocant (1604) | Drusius stated "Galatinus first led us to this mistake ... I know [of] nobody who read [it] thus earlier.."). An editor of Drusius in 1698 knows of an earlier reading in Porchetus de Salvaticis however. John Drusius wrote that neither יְהֹוָה nor יֱהֹוִה accurately represented God's name. |

| Sixtinus Amama (1593–1659) | De nomine tetragrammato (1628) | Sixtinus Amama, was a Professor of Hebrew in the University of Franeker. A pupil of Drusius. |

| Louis Cappel (1585–1658) | De nomine tetragrammato (1624) | Lewis Cappel reached the conclusion that Hebrew vowel points were not part of the original Hebrew language. This view was strongly contested by John Buxtorff the elder and his son. |

| James Altingius (1618–1679) | Exercitatio grammatica de punctis ac pronunciatione tetragrammati | James Altingius was a learned German divine. | |

Discourses defending Jehovah

| Author | Discourse | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Nicholas Fuller (1557–1626) | Dissertatio de nomine יהוה | Nicholas was a Hebraist and a theologian. |

| John Buxtorf (1564–1629) | Disserto de nomine JHVH (1620); Tiberias, sive Commentarius Masoreticus (1664) | John Buxtorf the elder opposed the views of Elia Levita regarding the late origin (invention by the Masoretes) of the Hebrew vowel points, a subject which gave rise to the controversy between Louis Cappel and his (e.g. John Buxtorf the elder's) son, Johannes Buxtorf II the younger. |

| Johannes Buxtorf II (1599–1664) | Tractatus de punctorum origine, antiquitate, et authoritate, oppositus Arcano puntationis revelato Ludovici Cappelli (1648) | Continued his father's arguments that the pronunciation and therefore the Hebrew vowel points resulting in the name Jehovah have divine inspiration. |

| Thomas Gataker (1574–1654) | De Nomine Tetragrammato Dissertaio (1645) | See Memoirs of the Puritans Thomas Gataker. |

| John Leusden (1624–1699) | Dissertationes tres, de vera lectione nominis Jehova | John Leusden wrote three discourses in defense of the name Jehovah. |

Summary of discourses

In A Dictionary of the Bible (1863), William Robertson Smith summarized these discourses, concluding that "whatever, therefore, be the true pronunciation of the word, there can be little doubt that it is not Jehovah". Despite this, he consistently uses the name Jehovah throughout his dictionary and when translating Hebrew names. Some examples include Isaiah [Jehovah's help or salvation], Jehoshua [Jehovah a helper], Jehu [Jehovah is He]. In the entry, Jehovah, Smith writes: "JEHOVAH (יְהֹוָה, usually with the vowel points of אֲדֹנָי; but when the two occur together, the former is pointed יֱהֹוִה, that is with the vowels of אֱלֹהִים, as in Obad. i. 1, Hab. iii. 19:" This practice is also observed in many modern publications, such as the New Compact Bible Dictionary (Special Crusade Edition) of 1967 and Peloubet's Bible Dictionary of 1947.

Usage in English

The following works render the Tetragrammaton as Jehovah, either exclusively or occasionally:

- William Tyndale, in his 1530 translation of the first five books of the English Bible, at Exodus 6:3 renders the divine name as Iehovah. In his foreword to this edition he wrote: "Iehovah is God's name... Moreover, as oft as thou seeist LORD in great letters (except there be any error in the printing) it is in Hebrew Iehovah."

- The Authorized King James Version, 1611: four times as the personal name of God (in all capitals): Exodus 6:3; Psalm 83:18; Isaiah 12:2; Isaiah 26:4; and three times in place names: Genesis 22:14; Exodus 17:15; and Judges 6:24.

- Young's Literal Translation by J.N. Young, 1862, 1898 renders the Tetragrammaton as Jehovah 6,831 times.

- In the Emphatic Diaglott, 1864, a translation of the New Testament by Benjamin Wilson, the name Jehovah appears 18 times.

- The English Revised Version, 1885, renders the Tetragrammaton as JEHOVAH (in all capitals) 12 times, as the personal name of God, in all the places that the King James Version renders it, and also in Exodus 6:2,6,7,8; Psalm 68:20; Isaiah 49:14; Jeremiah 16:21; Habakkuk 3:19.

- The Darby Bible, by John Nelson Darby renders the Tetragrammaton as Jehovah 6,810 times.

- The American Standard Version, 1901, renders the Tetragrammaton as Je-ho’vah in 6,823 places in the Old Testament.

- The Modern Reader's Bible, 1914, by Richard Moulton, uses Jehovah at Ps.83:18; Ex.6:2-9; Ex.22:14; Ps.68:4; Jerm.16:20; Isa.12:2 and Isa. 26:4.

- The New English Bible, published by Oxford University Press, 1970: e.g. Gen 22:14; Exodus 3:15,16; 6:3; 17:15; Judges 6:24

- The Living Bible, published by Tyndale House Publishers, Illinois 1971, uses Jehovah extensively, as in the 1901 American Standard Version, on which it is based.

- The Bible in Living English, by Steven T. Byington, published by the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, 1972, renders the word Jehovah throughout the Old Testament, as the proper name for God, over 6,800 times.

- The Bible in Today's English ( Good News Bible), published by the American Bible Society, 1976, uses The Lord in its translation, stating in its preface, "the distinctive Hebrew name for God (usually transliterated Jehovah or Yahweh) is in this translation represented by 'The Lord'." A footnote to Exodus 3:14 states, "Yahweh, traditionally transliterated as Jehovah."

- The New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures, published by the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, 1961 and revised 1984: Jehovah appears 7,210 times, comprising 6,973 instances in the Old Testament, and 237 times in the New Testament where the Tetragrammaton does not appear in Greek.

- Green's Literal Translation (1985) by Jay P. Green, Sr., renders the Tetragrammaton as Jehovah 6,866 times.

Recent English translations, including the New Jerusalem Bible (1985), the Amplified Bible (1987), the New Living Translation (1996), the English Standard Version (2001), and the Holman Christian Standard Bible (2004) use Yahweh, rather than Jehovah.

Following the Middle Ages, many Catholic churches and public buildings across Europe were decorated with the name, Jehovah. For example, the Coat of Arms of Plymouth (UK) City Council bears the Latin inscription, "Turris fortissima est nomen Jehova", derived from Proverbs 18:10.

Jehovah has been a popular English word for the personal name of God for several centuries. Christian hymns feature the name. Some religious groups, notably Jehovah's Witnesses and the King-James-Only movement, make prominent use of the name.