Herrerasaurus

Background Information

This content from Wikipedia has been selected by SOS Children for suitability in schools around the world. Sponsoring children helps children in the developing world to learn too.

| Herrerasaurus Temporal range: Middle Triassic, 231.4Ma |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Mounted skeleton cast, Senckenberg Museum | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Herrerasauridae |

| Genus: | †Herrerasaurus Reig, 1963 |

| Species: | † H. ischigualastensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis Reig, 1963 |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Ischisaurus cattoi Reig, 1963 |

|

Herrerasaurus was one of the earliest dinosaurs. Its name means "Herrera's lizard", after the rancher who discovered the first specimen. All known fossils of this carnivorous dinosaur have been discovered in rocks of late Ladinian age (middle Triassic according to the ICS, dated to 231.4 million years ago) in northwestern Argentina. The type species, Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis, was described by Osvaldo Reig in 1963 and is the only species assigned to the genus. Ischisaurus and Frenguellisaurus are synonyms.

For many years, the classification of Herrerasaurus was unclear because it was known from very fragmentary remains. It was hypothesized to be a basal theropod, a basal sauropodomorph, a basal saurischian, or not a dinosaur at all but an archosaur. However, with the discovery of an almost complete skeleton and skull in 1988, Herrerasaurus has been classified as either an early theropod or an early saurischian in at least five recent reviews of theropod evolution, with many researchers treating it at least tentatively as the most primitive member of Theropoda.

It is a member of the Herrerasauridae, a family of similar genera that were among the earliest of the dinosaurian evolutionary radiation.

Description

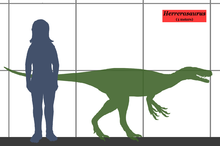

Herrerasaurus was a lightly built bipedal carnivore with a long tail and a relatively small head. Its length is estimated at 3 to 6 meters (10 to 20 ft), and its hip height at more than 1.1 meters (3.3 ft). It may have weighed around 210–350 kilograms (463–772 lb). In a large specimen, at first thought to belong to a separate genus, Frenguellisaurus, the skull measured 56 centimeters (1.8 ft) in length. Smaller specimens had skulls about 30 centimeters (1 ft) long.

Skull

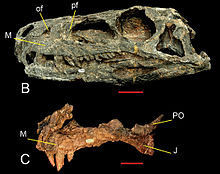

Herrerasaurus had a long, narrow skull that lacked nearly all the specializations that characterized later dinosaurs, and more closely resembled those of more primitive archosaurs such as Euparkeria. It had five pairs of fenestrae (skull openings) in its skull, two pairs of which were for the eyes and nostrils. Between the eyes and the nostrils were two antorbital fenestrae and a pair of tiny, 1-centimeter-long (0.4 in) slit-like holes called promaxillary fenestrae. Behind the eyes were large infratemporal fenestrae. These fenestrae reduce the weight of the skull.

Herrerasaurus had a flexible joint in the lower jaw that could slide back and forth to deliver a grasping bite. This cranial specialization is unusual among dinosaurs but has evolved independently in some lizards. The rear of the lower jaw also had fenestrae. The jaws were equipped with large serrated teeth for biting and eating flesh, and the neck was slender and flexible.

Limbs

The forelimbs of Herrerasaurus were less than half the length of its hind limbs. The upper arm and forearm were rather short, while the manus (hand) was elongated. The first two fingers and the thumb ended in curved, sharp claws for grasping prey. The fourth and fifth digits were small stubs without claws.

Herrerasaurus was fully bipedal. It had strong hind limbs with short thighs and rather long feet, indicating that it was likely a swift runner. The foot had five toes, but only the middle three (digits II, III, and IV) bore weight. The outer toes (I and V) were small; the first toe had a small claw. The tail, partially stiffened by overlapping vertebral projections, balanced the body and was also an adaptation for speed.

Derived and basal characteristics

Herrerasaurus is something of an enigma in that it displays traits that are found in different groups of dinosaurs, and several traits found in non-dinosaurian archosaurs. Although it shares most of the characteristics of dinosaurs, there are a few differences, particularly in the shape of its hip and leg bones. Its pelvis is like that of saurischian dinosaurs, but it has a bony acetabulum (where the femur meets the pelvis) that was only partially open. The ilium, the main hip bone, is supported by only two sacrals, a basal trait,. However, the pubis points backwards, a derived trait as seen in dromaeosaurids and birds. Additionally, the end of the pubis has a booted shape, like those in avetheropods; and the vertebral centra has an hourglass shape as found in Allosaurus.

Classification

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The upper cladogram follows an analysis by M.D. Ezcurra in 2010. In it, Herrerasaurus is a primitive saurischian but not a theropod. The lower cladogram is based on an analysis by S. Nesbitt, in 2011. This analysis indicates that Herrerasaurus was a basal theropod. |

Herrerasaurus gives its name to its family, Herrerasauridae, a group of similar animals from the Late Triassic which were among the earliest of the dinosaurian evolutionary radiation. Where it and its close relatives lie on the early dinosaur evolutionary tree is unclear. Most 21st-century analyses have found them to be basal theropods, though they may in fact represent basal saurischians or even be non-dinosaurian, predating the saurischian-ornithischian split. Most analyses, such as those by Sterling Nesbitt and colleagues (2009, 2011), have found Herrerasaurus and its relatives to be very basal theropods. Others (such as Ezcurra 2010) have found them to be basal to the clade Eusaurischia, that is, closer to the base of the saurischian tree than either true theropods or sauropodomorphs, but not members of either group. The situation is further complicated by uncertainties in correlating the ages of late Triassic beds bearing land animals.

Other members of the clade may include Eoraptor from the same Ischigualasto Formation of Argentina as Herrerasaurus, Staurikosaurus from the Santa Maria Formation of southern Brazil, Chindesaurus from the Upper Petrified Forest ( Chinle Formation) of Arizona, and possibly Caseosaurus from the Dockum Formation of Texas, although the relationships of these animals are not fully understood, and not all paleontologists agree. Other possible basal theropods, Alwalkeria from the Late Triassic Maleri Formation of India, and Teyuwasu, known from very fragmentary remains from the Late Triassic of Brazil, might be related. Novas (1992) defined Herrerasauridae as Herrerasaurus, Staurikosaurus, and their most recent common ancestor. Sereno (1998) defined the group as the most inclusive clade including H. ischigualastensis but not Passer domesticus. Langer (2004) provided first phylogenetic definition of a higher level taxon, infraorder Herrerasauria.

History

Herrerasaurus was named by paleontologist Osvaldo Reig after Victorino Herrera, an Andean goatherd who first noticed its fossils in outcrops near the city of San Juan in 1959. These rocks, which later yielded Eoraptor, are part of the Ischigualasto Formation and date from the late Ladinian to early Carnian stages of the Late Triassic period. Reig named a second dinosaur from these rocks in the same publication as Herrerasaurus; this dinosaur, Ischisaurus cattoi, is now considered a junior synonym and a juvenile of Herrerasaurus. Two other partial skeletons, with skull material, were named Frenguellisaurus ischigualastensis by Fernando Novas in 1986, but this species too is now thought to be a synonym.

Reig believed Herrerasaurus was an early example of a carnosaur, but this was the subject of much debate over the next 30 years, and the genus was variously classified during that time. In 1970, Steel classified Herrerasaurus as a prosauropod. In 1972, Peter Galton classified the genus as not diagnosable beyond Saurischia. Later, using cladistic analysis, some researchers put Herrerasaurus and Staurikosaurus at the base of the dinosaur tree before the separation between ornithischians and saurischians. Several researchers classified the remains as non-dinosaurian.

A complete Herrerasaurus skull was not found until 1988, by a team of paleontologists led by Paul Sereno. Based on the new fossils, authors such as Thomas Holtz and Jose Bonaparte classified Herrerasaurus at the base of the saurischian tree before the divergence between prosauropods and theropods. However, Sereno favored classifying Herrerasaurus (and the Herrerasauridae) as primitive theropods. These two classifications have become the most persistent, with Rauhut (2003) and Bittencourt and Kellner (2004) favoring the early theropod hypothesis, and Max Langer (2004), Langer and Benton (2006), and Randall Irmis and his coauthors (2007) favoring the basal saurischian hypothesis. If Herrerasaurus were indeed a theropod, it would indicate that theropods, sauropodomorphs, and ornithischians diverged even earlier than herrerasaurids, before the middle Carnian, and that "all three lineages independently evolved several dinosaurian features, such as a more advanced ankle joint or an open acetabulum". This view is further supported by ichnological records showing large tridactyl (three-toed) footprints that can be attributed only to a theropod dinosaur. These footprints date from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the Los Rastros Formation in Argentina and predate Herrerasaurus by 3 to 5 million years.

The study of early dinosaurs such as Herrerasaurus and Eoraptor therefore has important implications for the concept of dinosaurs as a monophyletic group (a group descended from a common ancestor). The monophyly of dinosaurs was explicitly proposed in the 1970s by Galton and Robert T. Bakker, who compiled a list of cranial and postcranial synapomorphies (common anatomical traits derived from the common ancestor). Later authors proposed additional synapomorphies. An extensive study of Herrerasaurus by Sereno in 1992 suggested that of these proposed synapomorphies, only one cranial and seven postcranial features were actually derived from a common ancestor, and that the others were attributable to convergent evolution. Sereno's analysis of Herrerasaurus also led him to propose several new dinosaurian synapomorphies.

Paleoecology

Although Herrerasaurus shared the body shape of the large carnivorous dinosaurs, it lived about 230 million years ago, a time when dinosaurs were small and insignificant. It was the time of non-dinosaurian reptiles, not dinosaurs, and a major turning point in the Earth's ecology. The vertebrate fauna of the Ischigualasto Formation and the slightly later Los Colorados Formation consisted mainly of a variety of crurotarsal archosaurs and synapsids. For instance, in the Ischigualasto Formation, dinosaurs constituted only about 6% of the total number of fossils. By the end of the Triassic Period, dinosaurs were becoming the dominant large land animals, and the other archosaurs and synapsids declined in variety and number.

Studies suggest that the paleoenvironment of the Ischigualasto Formation was a volcanically active floodplain covered by forests and subject to strong seasonal rainfalls. The climate was moist and warm, though subject to seasonal variations. Vegetation consisted of ferns ( Cladophlebis), horsetails, and giant conifers (Protojuniperoxylon). These plants formed highland forests along the banks of rivers. Herrerasaurus remains appear to have been the most common among the carnivores of the Ischigualasto Formation. It lived in the jungles of Late Triassic South America alongside another early dinosaur, the one metre long Eoraptor, as well as Saurosuchus, a giant land-living rauisuchian (a quadrupedal meat eater with a theropod-like skull); the broadly similar but smaller Venaticosuchus, an ornithosuchid; and the predatory chiniquodontids. Herbivores were much more abundant than carnivores and were represented by rhynchosaurs such as Hyperodapedon (a beaked reptile); aetosaurs (spiny armored reptiles); kannemeyeriid dicynodonts (stocky, front-heavy beaked quadrupedal animals) such as Ischigualastia; and traversodontids (somewhat similar in overall form to dicynodonts, but lacking beaks) such as Exaeretodon. These non-dinosaurian herbivores were much more abundant than early ornithischian dinosaurs like Pisanosaurus.

Paleobiology

The teeth of Herrerasaurus indicate that it was a carnivore; its size indicates it would have preyed upon small and medium-sized plant eaters. These might have included other dinosaurs, such as Pisanosaurus, as well as the more plentiful rhynchosaurs and synapsids. Herrerasaurus itself may have been preyed upon by giant rauisuchids like Saurosuchus; puncture wounds were found in one skull.

Coprolites (fossilized dung) containing small bones but no trace of plant fragments, discovered in the Ischigualasto Formation, have been assigned to Herrerasaurus based on fossil abundance. Mineralogical and chemical analysis of these coprolites indicates that if the referral to Herrerasaurus was correct, this carnivore could digest bone.

Comparisons between the scleral rings of Herrerasaurus and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been cathemeral, active throughout the day at short intervals.

Paleopathology

In a 2001 study conducted by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, 12 hand bones and 20 foot bones referred to Herrerasaurus were examined for signs of stress fracture, but none were found.

PVSJ 407, a Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis had a pit in a skull bone attributed to a bite by Paul Sereno and Novas. Two additional pits occurred on the splenial. The area around these pits are swollen and porous, suggesting the wounds were afflicted by a short-lived non-lethal infection. Because of the size and angles of the wound, its likely that they were obtained in a fight with another Herrerasaurus.