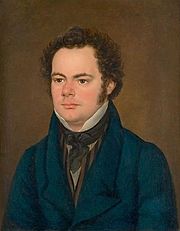

Franz Schubert

Background to the schools Wikipedia

The articles in this Schools selection have been arranged by curriculum topic thanks to SOS Children volunteers. All children available for child sponsorship from SOS Children are looked after in a family home by the charity. Read more...

Franz Peter Schubert ( January 31, 1797 – November 19, 1828) was an Austrian composer. He wrote some 600 lieder, nine symphonies (including the famous " Unfinished Symphony"), liturgical music, operas, and a large body of chamber and solo piano music. He is particularly noted for his original melodic and harmonic writing.

While Schubert had a close circle of friends and associates who admired his work (including his teacher Antonio Salieri, and the prominent singer Johann Michael Vogl), wider appreciation of his music during his lifetime was limited at best. He was never able to secure adequate permanent employment, and for most of his career he relied on the support of friends and family. Interest in Schubert's work increased dramatically in the decades following his death and he is now widely considered to be one of the greatest composers in the Western tradition.

Biography

Early life and education

Schubert was born in Vienna on January 31, 1797. His father, Franz Theodor Schubert, the son of a Moravian peasant, was a parish schoolmaster; his mother, Elizabeth Vietz was the daughter of a Silesian master locksmith, and had also been a housemaid for a Viennese family prior to her marriage. Of the Schuberts' sixteen children (one illegitimate child was born in 1783), eleven died in infancy; five survived. Their father Franz Theodor was a well-known teacher, and his school on the Himmelpfortgrund, a part of Vienna's 9th district, was well attended. He was not a famous musician, but he taught his son what he could of music.

At the age of five, Schubert began receiving regular instruction from his father and a year later was enrolled at the Himmelpfortgrund school. His formal musical education also began around the same time. His father continued to teach him the basics of the violin. At seven, Schubert was placed under the instruction of Michael Holzer. Holzer's lessons seem to have mainly consisted of conversations and expressions of admiration and the boy gained more from his acquaintance with a friendly joiner's apprentice who used to take him to a neighboring pianoforte warehouse where he was given the opportunity to practice on better instruments. The unsatisfactory nature of Schubert's early training was even more pronounced during his time given that composers could expect little chance of success unless they were also able to appeal to the public as performers. To this end, Schubert's meager musical education was never entirely sufficient.

In October 1808, he was received as a pupil at the Stadtkonvikt (Imperial religious boarding school) through a choir scholarship. It was at the Stadtkonvikt that Schubert was introduced to the overtures and symphonies of Mozart. His exposure to these pieces as well as various lighter compositions combined with his occasional visits to the opera set the foundation for his greater musical knowledge.

Meanwhile, his genius was already beginning to show itself in his compositions. Antonio Salieri, a leading composer of the period, became aware of the talented young man and decided to train him in musical composition and music theory. Schubert's early essay in chamber music is noticeable, since we learn that at the time a regular quartet-party was established at his home "on Sundays and holidays," in which his two brothers played the violin, his father the cello and Franz himself the viola. It was the first germ of that amateur orchestra for which, in later years, many of his compositions were written. During the remainder of his stay at the Stadtkonvikt he wrote a good deal more chamber music, several songs, some miscellaneous pieces for the pianoforte and, among his more ambitious efforts, a Kyrie (D.31) and Salve Regina (D.27), an octet for wind instruments (D.72/72a) (said to commemorate the death of his mother, which took place in 1812) a cantata (D.110), words and music, for his father's name-day in 1813, and the closing work of his school-life, his first symphony (D.82).

Teacher at his father's school

At the end of 1813 he left the Stadtkonvikt, and entered his father's school as teacher of the lowest class. In the meantime, his father remarried, this time to Anna Kleyenboeck, the daughter of a silk dealer from the suburb Gumpendorf. For over two years the young man endured the drudgery of the work, which he performed with very indifferent success. There were, however, other interests to compensate. He received private lessons in composition from Salieri, who did more for Schubert’s training than any of his other teachers.

Supported by friends

As 1815 was the most prolific period of Schubert's life, 1816 saw the first real change in his fortunes. Somewhere about the turn of the year his old schoolfriend Joseph von Spaun surprised him in the composition of Erlkönig (D.328, published as Op.1) — Goethe's poem propped among a heap of exercise books, and the boy at white-heat of inspiration "hurling" the notes on the music-paper. A few weeks later Franz von Schober, a student of good family and some means, who had heard some of Schubert's songs at Spaun's house, came to pay a visit to the composer and proposed to carry him off from school-life and give him freedom to practise his art in peace. The proposal was particularly opportune, for Schubert had just made an unsuccessful application for the post of Kapellmeister at Laibach and was feeling more acutely than ever the slavery of the classroom. His father's consent was readily given, and before the end of the spring he was installed as a guest in Schober's lodgings. For a time he attempted to increase the household resources by giving music lessons, but they were soon abandoned, and he devoted himself to composition. "I write all day," he said later to an inquiring visitor, "and when I have finished one piece I begin another."

All this time his circle of friends was steadily widening. Mayrhofer introduced him to Johann Michael Vogl, a famous baritone, who did him good service by performing his songs in the salons of Vienna; Anselm Hüttenbrenner and his brother Joseph ranged themselves among his most devoted admirers; Joseph von Gahy, an excellent pianist, played his sonatas and fantasias; the Sonnleithners, a burgher family whose eldest son had been at the Stadtkonvikt, gave him free access to their home, and organized in his honour musical parties which soon assumed the name of Schubertiaden. The material needs of life were supplied without much difficulty. No doubt Schubert was entirely penniless, for he had given up teaching, he could earn nothing by public performance, and, as yet, no publisher would take his music at a gift; but his friends came to his aid with true Bohemian generosity — one found him lodging, another found him appliances, they took their meals together and the man who had any money paid the score. Schubert was always the leader of the party, but more often than not, was penniless. Though he was known by half a dozen affectionate nicknames, the most characteristic was kann er was? ("Is he good for anything?"), or more colloquially, "Can he pay?" (for the food and drink), his usual question when a new acquaintance was introduced. Another nickname was "The Little Mushroom" as Schubert was only five feet, one and one-half inches tall (1.56 m), and tended to corpulence.

The compositions of 1820 are remarkable, and show a marked advance in development and maturity of style. The unfinished oratorio "Lazarus" (D.689) was begun in February; later followed, amid a number of smaller works, by the 23rd Psalm (D.706), the Gesang der Geister (D.705/714), the Quartettsatz in C minor (D.703), and the "Wanderer Fantasy" for piano (D.760). But of almost more biographical interest is the fact that in this year two of Schubert's operas appeared at the Kärntnerthor Theatre, Die Zwillingsbrüder (D.647) on June 14, and Die Zauberharfe (D.644) on August 19. Hitherto his larger compositions (apart from Masses) had been restricted to the amateur orchestra at the Gundelhof, a society which grew out of the quartet-parties at his home. Now he began to assume a more prominent position and address a wider public. Still, however, publishers remained obstinately aloof, and it was not until his friend Vogl had sung Erlkönig at a concert (Feb. 8, 1821) that Anton Diabelli hesitatingly agreed to print some of his works on commission. The first seven opus numbers (all songs) appeared on these terms; then the commission ceased, and he began to receive the meagre pittances which were all that the great publishing houses ever accorded to him. Much has been written about the neglect from which he suffered during his lifetime. It was not the fault of his friends, it was only indirectly the fault of the Viennese public; the persons most to blame were the cautious intermediaries who stinted and hindered him from publication.

The production of his two dramatic pieces turned Schubert's attention more firmly than ever in the direction of the stage; and towards the end of 1821 he set himself on a course which for nearly three years brought him continuous mortification and disappointment. Alfonso und Estrella was refused, and so was Fierrabras (D.796); Die Verschworenen (D.787) was prohibited by the censor (apparently on the ground of its title); Rosamunde (D.797) was withdrawn after two nights, owing to the poor quality of its libretto. Of these works the two former are written on a scale which would make their performances exceedingly difficult (Fierabras, for instance, contains over 1,000 pages of manuscript score), but Die Verschworenen is a bright attractive comedy, and Rosamunde contains some of the most charming music that Schubert ever composed. In 1822 he made the acquaintance both of Weber and of Beethoven, but little came of it in either case, though Beethoven cordially acknowledged his genius, the quote attributed to Beethoven being: "Truly, the spark of divine genius resides in this Schubert!" Schober was away from Vienna; new friends appeared of a less desirable character; on the whole these were the darkest years of his life.

In 1994 musicologist Rita Steblin discovered Schubert's brother Karl's marriage petition on the attic floor of the Lichtental church. The composer's own wish to marry Therese Grob was hindered by Metternich's harsh marriage consent law of 1815, as Schubert's heart-rending cry in his diary of September 1816 makes clear.

Last years and masterworks

In 1823 appeared Schubert's first song cycle, Die schöne Müllerin (D.795), after poems by Wilhelm Müller. This work, together with the later cycle " Winterreise" (D.911; also written to texts of Müller) is widely considered one of the pinnacles of Lieder. The song Du bist die Ruh ("You are stillness/peace") D.776 was also composed during this year.

In the spring of 1824 he wrote the Octet in F (D.803), "A Sketch for a Grand Symphony"; and in the summer went back to Želiezovce, when he became attracted by Hungarian idiom, and wrote the Divertissement a l'Hongroise (D.818) and the String Quartet in A minor (D.804). It has been said that he held a hopeless passion for his pupil Countess Karoline Eszterházy; if this is the case, the details are unknown to historians.

Despite his preoccupation with the stage and later with his official duties, he found time during these years for a good deal of miscellaneous composition. The Mass in A flat (D.678) was completed and the "Unfinished Symphony" ( Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D.759) begun in 1822. The question of why the symphony was "unfinished" has been debated endlessly and is still unresolved. To 1824, beside the works mentioned above, belong the variations for flute and piano on Trockne Blumen, from the cycle Die schöne Müllerin. There is also a sonata for piano and arpeggione (D.821). This music is nowadays usually played by either cello or viola and piano, although a number of other arrangements have been made.

The mishaps of the recent years were compensated by the prosperity and happiness of 1825. Publication had been moving more rapidly; the stress of poverty was for a time lightened; in the summer there was a pleasant holiday in Upper Austria, where Schubert was welcomed with enthusiasm. It was during this tour that he produced his "Songs from Sir Walter Scott". This cycle contains his famous and beloved Ellens dritter Gesang (D.839). This is today more popularly, though mistakenly, referred to as "Schubert's Ave Maria"; while he had set it to Adam Storck's German translation of Scott's hymn from The Lady of the Lake that happens to open with the greeting Ave Maria and also has it for its refrain, subsequently the entire Scott/Storck text in Schubert's song have occasionally been substituted with the complete Latin text of the traditional Ave Maria prayer. During this time he also wrote the Piano Sonata in A minor (D.845, Op. 42) and the Symphony No. 9 (in C major, D.944), which is believed to have been completed the following year, in 1826.

From 1826 to 1828 Schubert resided continuously in Vienna, except for a brief visit to Graz in 1827. The history of his life during these three years is little more than a record of his compositions. There were few events worth mention during this period. In 1826, he dedicated a symphony to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde and received an honorarium in return. In the spring of 1828 he gave, for the first and only time in his career, a public concert of his own works which was very well received. But the compositions themselves are a sufficient biography. The String Quartet in D minor (D.810), with the variations on Death and the Maiden, was written during the winter of 1825–1826, and first played on January 25, 1826. Later in the year came the String Quartet in G major, the "Rondeau brilliant" for piano and violin (D.895, Op.70), and the Piano Sonata in G (D.894, Op.78) (first published under the title "Fantasia in G"). To these should be added the three Shakespearian songs, of which "Hark! Hark! the Lark" (D.889) and "Who is Sylvia?" (D.891) were allegedly written on the same day, the former at a tavern where he broke his afternoon's walk, the latter on his return to his lodging in the evening.

In 1827 Schubert wrote the song cycle Winterreise (D.911), a colossal peak of the art of art-song (remarkable is already the way it was presented at the Schubertiades), the Fantasia for piano and violin in C (D.934), and the two piano trios (B flat, D.898; and E flat, D.929): in 1828 the Song of Miriam, the Mass in E-flat (D.950), the Tantum Ergo (D.962) in the same key, the String Quintet in C (D.956), the second Benedictus to the Mass in C, the last three piano sonatas, and the collection of songs published posthumously under the fanciful name of Schwanengesang ("Swan-song", D.957), which whilst not a true song cycle, retains a unity of style amongst the individual songs, touching unwonted depths of tragedy and the morbidly supernatural. Six of these are to words by Heinrich Heine, whose Buch der Lieder appeared in the autumn. The Symphony No. 9 (D.944) is dated 1828, and many modern Schubert scholars (including Brian Newbould) believe that this symphony, written in 1825-6, was revised for performance in 1828 (a fairly unusual practice for Schubert, for whom publication, let alone performance, was rarely contemplated for many of his larger-scale works during his lifetime). In the last weeks of his life he began to sketch three movements for a new Symphony in D (D.936A).

The works of his last two years reveal a composer increasingly meditating on the darker side of the human psyche and human relationships, and with a deeper sense of spiritual awareness and conception of the 'beyond', reaching extraordinary depths in several chillingly dark songs of this period, especially in the larger cycles, (the song Der Doppelgaenger reaching an extraordinary climax, conveying madness at the realization of rejection and imminent death, and yet able to touch repose and communion with the infinite in the almost timeless ebb and flow of the String Quintet). Schubert expressed the wish, were he to survive his final illness, to further develop his knowledge of harmony and counterpoint.

Death

In the midst of this creative activity, his health deteriorated. He contracted syphilis in 1822. The final illness may have been typhoid fever, though other causes have been proposed; some of his final symptoms match those of mercury poisoning (mercury was a common treatment for syphilis in the early 19th century). At any rate, insufficient evidence remains to make a definitive diagnosis. His solace in his final illness was reading, and he had become a passionate fan of the writings of James Fenimore Cooper. He died aged 31 on Wednesday November 19, 1828 at the apartment of his brother Ferdinand in Vienna. At 3 p.m. "someone observed that he had ceased to breathe." By his own request, he was buried next to Beethoven, whom he had adored all his life, in the village cemetery of Währing. In 1888, both Schubert's and Beethoven's graves were moved to the Zentralfriedhof, where they can now be found next to those of Johann Strauss II and Johannes Brahms.

In 1872, a memorial to Franz Schubert was erected in Vienna's Stadtpark.

Music

Style

Schubert composed music for a wide range of ensembles and in various genres including opera, liturgical music, chamber and solo piano music.

While he was clearly influenced by the Classical sonata forms of Beethoven and Mozart (his early works, among them notably the 5th Symphony, are particularly Mozartean), his formal structures and his developments tend to give the impression more of melodic development than of harmonic drama. This combination of Classical form and long-breathed Romantic melody sometimes lends them a discursive style: his 9th Symphony was described by Robert Schumann as running to "heavenly lengths". His harmonic innovations include movements in which the first section ends in the key of the subdominant rather than the dominant (as in the last movement of the Trout Quintet). Schubert's practice here was a forerunner of the common Romantic technique of relaxing, rather than raising, tension in the middle of a movement, with final resolution postponed to the very end.

It was in the genre of the Lied, however, that Schubert made his most indelible mark. Plantinga remarks, "In his more than six hundred lieder he explored and expanded the potentialities of the genre as no composer before him." Prior to Schubert's influence, lieder tended toward a strophic, syllabic treatment of text, evoking the folksong qualities burgeoned by the stirrings of Romantic nationalism. Among Schubert's treatments of the poetry of Goethe, his settings of Gretchen am Spinnrade and Der Erlkönig are particularly striking for their dramatic content, forward-looking uses of harmony, and their use of eloquent pictorial keyboard figurations, such as the depiction of the spinning wheel and treadle in the piano in Gretchen and the furious and ceaseless gallop the right hand in Erlkönig. Also of particular note are his two song cycles on the poems of Wilhelm Müller, Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise, and the collection Schwanengesang, all of which helped to establish the genre and its potential for musical, poetic, and dramatic narrative. In turn, Schubert's work in Lieder fostered interest in shorter and more lyrical instrumental works.

Schubert's compositional style progressed rapidly throughout his short life. The loss of potential masterpieces caused by his early death at 31 was perhaps best expressed in the epitaph on his tombstone written by the poet Franz Grillparzer, "Here music has buried a treasure, but even fairer hopes."

Posthumous history of Schubert's music

Some of his smaller pieces were printed shortly after his death, but the more valuable seem to have been regarded by the publishers as so much waste paper. In 1838 Robert Schumann, on a visit to Vienna, found the dusty manuscript of the C major symphony (the "Great", D.944) and took it back to Leipzig, where it was performed by Felix Mendelssohn and celebrated in the Neue Zeitschrift. There continues to be some controversy over the numbering of this symphony, with German-speaking scholars numbering it as symphony No. 7, the revised Deutsch catalogue (the standard catalogue of Schubert's works, compiled by Otto Erich Deutsch) listing it as No. 8, and English-speaking scholars listing it as No. 9.

Fifty of his songs were transcribed for piano by Franz Liszt, who declared Schubert to be "the most poetic musician who has ever lived".

The most important step towards the recovery of the neglected works was the journey to Vienna which Sir George Grove (of " Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians" fame) and Arthur Sullivan made in the autumn of 1867. The travellers rescued from oblivion seven symphonies, the Rosamunde incidental music, some of the Masses and operas, some of the chamber works, and a vast quantity of miscellaneous pieces and songs. This led to more widespread public interest in Schubert's work.

Another controversy, which originated with Grove and Sullivan and continued for many years, surrounded the "lost" symphony. Immediately before Schubert's death, his friend Eduard von Bauernfeld recorded the existence of an additional symphony, dated 1828 (although this does not necessarily indicate the year of composition) named the "Letzte" or "Last" symphony. It has been more or less accepted by musicologists that the "Last" symphony refers to a sketch in D major (D.936A), identified by Ernst Hilmar in 1977, and which was realised by Brian Newbould as the Tenth Symphony.

Catalogue

- Lists of works by Franz Schubert

- By Deutsch number: D 1 to 504 - D 505 to 998

- List of compositions by Franz Schubert — by musical genre

- Alphabetical list of Schubert's compositions (insofar as described in separate articles)