Effects of nuclear explosions

Did you know...

SOS Children has tried to make Wikipedia content more accessible by this schools selection. All children available for child sponsorship from SOS Children are looked after in a family home by the charity. Read more...

The energy released from a nuclear weapon detonated in the troposphere can be divided into four basic categories:

- Blast—40-50% of total energy

- Thermal radiation—30-50% of total energy

- Ionizing radiation—5% of total energy

- Residual radiation—5-10% of total energy

However, depending on the design of the weapon and the environment in which it is detonated the energy distributed to these categories can be increased or decreased to the point of nullification. The blast effect is created by immense amounts of energy, spanning the electromagnetic spectrum, with the surroundings. Locations such as submarine, surface, airburst, or exo-atmospheric determine how much energy is produced as blast and how much as radiation. In general, denser mediums around the bomb, like water, absorb more energy, and create more powerful shockwaves while at the same time limiting the area of its effect.

The dominant effects of a nuclear weapon where people are likely to be affected (blast and thermal radiation) are identical physical damage mechanisms to conventional explosives. However the energy produced by a nuclear explosive is millions of times more powerful per gram and the temperatures reached are briefly in the tens of millions of degrees.

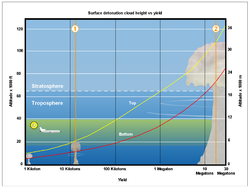

Energy from a nuclear explosive is initially released in several forms of penetrating radiation. When there is a surrounding material such as air, rock, or water, this radiation interacts with and rapidly heats it to an equilibrium temperature. This causes vaporization of surrounding material resulting in its rapid expansion. Kinetic energy created by this expansion contributes to the formation of a shockwave. When a nuclear detonation occurs in air near sea level, much of the released energy interacts with the atmosphere and creates a shockwave which expands spherically from the hypocenter. Intense thermal radiation at the hypocenter forms a fireball and if the burst is low enough, its often associated mushroom cloud. In a burst at high altitudes, where the air density is low, more energy is released as ionizing gamma radiation and x-rays than an atmosphere displacing shockwave.

In 1945 there was some initial speculation among the scientists developing the first nuclear weapons that there might be a possibility of igniting the Earth's atmosphere with a large enough nuclear explosion. This would concern a nuclear reaction of two nitrogen atoms forming a carbon and an oxygen atom, with release of energy. This energy would heat up the remaining nitrogen enough to keep the reaction going until all nitrogen atoms were consumed. This was, however, quickly shown to be unlikely enough to be considered impossible . Nevertheless, the notion has persisted as a rumour for many years.

Direct effects

Blast damage

The high temperatures and pressures cause gas to move outward radially in a thin, dense shell called "the hydrodynamic front." The front acts like a piston that pushes against and compresses the surrounding medium to make a spherically expanding shock wave. At first, this shock wave is inside the surface of the developing fireball, which is created in a volume of air by the X-rays. However, within a fraction of a second the dense shock front obscures the fireball, causing the characteristic double pulse of light seen from a nuclear detonation. For air bursts at or near sea-level between 50-60% of the explosion's energy goes into the blast wave, depending on the size and the yield-to-weight ratio of the bomb. As a general rule, the blast fraction is higher for low yield and/or high bomb mass. Furthermore, it decreases at high altitudes because there is less air mass to absorb radiation energy and convert it into blast. This effect is most important for altitudes above 30 km, corresponding to <1 per cent of sea-level air density.

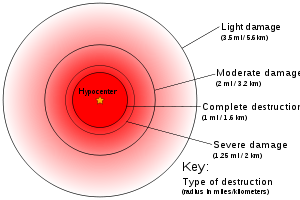

Much of the destruction caused by a nuclear explosion is due to blast effects. Most buildings, except reinforced or blast-resistant structures, will suffer moderate to severe damage when subjected to overpressures of only 35.5 kilopascals (kPa) (5.15 pounds-force per square inch or 0.35 atm).

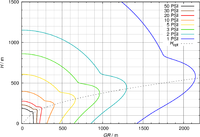

The blast wind may exceed one thousand km/h. The range for blast effects increases with the explosive yield of the weapon and also depends on the burst altitude. Contrary to what one might expect from geometry the blast range is not maximal for surface or low altitude blasts but increases with altitude up to an "optimum burst altitude" and then decreases rapidly for higher altitudes. This is due to the nonlinear behaviour of shock waves. If the blast wave reaches the ground it is reflected. Below a certain reflection angle the reflected wave and the direct wave merge and form a reinforced horizontal wave, the so-called Mach stem (named after Ernst Mach). For each goal overpressure there is a certain optimum burst height at which the blast range is maximized. In a typical air burst, where the blast range is maximized for 5 to 20 psi (35 to 140 kPa), these values of overpressure and wind velocity noted above will prevail at a range of 0.7 km for 1 kiloton (kt) of TNT yield; 3.2 km for 100 kt; and 15.0 km for 10 megatons (Mt) of TNT.

Two distinct, simultaneous phenomena are associated with the blast wave in air:

- Static overpressure, i.e., the sharp increase in pressure exerted by the shock wave. The overpressure at any given point is directly proportional to the density of the air in the wave.

- Dynamic pressures, i.e., drag exerted by the blast winds required to form the blast wave. These winds push, tumble and tear objects.

Most of the material damage caused by a nuclear air burst is caused by a combination of the high static overpressures and the blast winds. The long compression of the blast wave weakens structures, which are then torn apart by the blast winds. The compression, vacuum and drag phases together may last several seconds or longer, and exert forces many times greater than the strongest hurricane.

Acting on the human body, the shock waves cause pressure waves through the tissues. These waves mostly damage junctions between tissues of different densities ( bone and muscle) or the interface between tissue and air. Lungs and the abdominal cavity, which contain air, are particularly injured. The damage causes severe hemorrhaging or air embolisms, either of which can be rapidly fatal. The overpressure estimated to damage lungs is about 70 kPa. Some eardrums would probably rupture around 22 kPa (0.2 atm) and half would rupture between 90 and 130 kPa (0.9 to 1.2 atm).

Blast Winds: The drag energies of the blast winds are proportional to the cubes of their velocities multiplied by the durations. These winds may reach several hundred kilometers per hour.

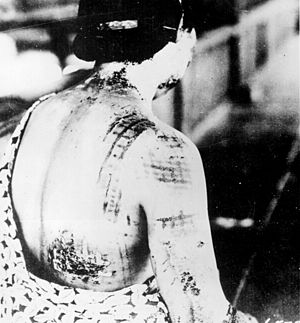

Thermal radiation

Nuclear weapons emit large amounts of electromagnetic radiation as visible, infrared, and ultraviolet light. The chief hazards are burns and eye injuries. On clear days, these injuries can occur well beyond blast ranges. The light is so powerful that it can start fires that spread rapidly in the debris left by a blast. The range of thermal effects increases markedly with weapon yield. Thermal radiation accounts for between 35-45% of the energy released in the explosion, depending on the yield of the device.

There are two types of eye injuries from the thermal radiation of a weapon:

Flash blindness is caused by the initial brilliant flash of light produced by the nuclear detonation. More light energy is received on the retina than can be tolerated, but less than is required for irreversible injury. The retina is particularity susceptible to visible and short wavelength infrared light, since this part of the electromagnetic spectrum is focused by the lens on the retina. The result is bleaching of the visual pigments and temporary blindness for up to 40 minutes.

A retinal burn resulting in permanent damage from scarring is also caused by the concentration of direct thermal energy on the retina by the lens. It will occur only when the fireball is actually in the individual's field of vision and would be a relatively uncommon injury. Retinal burns, however, may be sustained at considerable distances from the explosion. The apparent size of the fireball, a function of yield and range will determine the degree and extent of retinal scarring. A scar in the central visual field would be more debilitating. Generally, a limited visual field defect, which will be barely noticeable, is all that is likely to occur.

When thermal radiation strikes an object, part will be reflected, part transmitted, and the rest absorbed. The fraction that is absorbed depends on the nature and colour of the material. A thin material may transmit a lot. A light colored object may reflect much of the incident radiation and thus escape damage. The absorbed thermal radiation raises the temperature of the surface and results in scorching, charring, and burning of wood, paper, fabrics, etc. If the material is a poor thermal conductor, the heat is confined to the surface of the material.

Actual ignition of materials depends on how long the thermal pulse lasts and the thickness and moisture content of the target. Near ground zero where the energy flux exceeds 125 J/ cm², what can burn, will. Farther away, only the most easily ignited materials will flame. Incendiary effects are compounded by secondary fires started by the blast wave effects such as from upset stoves and furnaces.

In Hiroshima, a tremendous fire storm developed within 20 minutes after detonation and destroyed many more buildings and homes. A fire storm has gale force winds blowing in towards the centre of the fire from all points of the compass. It is not, however, a phenomenon peculiar to nuclear explosions, having been observed frequently in large forest fires and following incendiary raids during World War II.

Because thermal radiation travels more or less in a straight line from the fireball (unless scattered) any opaque object will produce a protective shadow. If fog or haze scatters the light, it will heat things from all directions and shielding will be less effective, but fog or haze would also diminish the range of these effects.

Indirect effects

Electromagnetic pulse

Gamma rays from a nuclear explosion produce high energy electrons through Compton scattering. These electrons are captured in the earth's magnetic field, at altitudes between twenty and forty kilometers, where they resonate. The oscillating electric current produces a coherent electromagnetic pulse (EMP) which lasts about one millisecond. Secondary effects may last for more than a second.

The pulse is powerful enough to cause long metal objects (such as cables) to act as antennas and generate high voltages when the pulse passes. These voltages, and the associated high currents, can destroy unshielded electronics and even many wires. There are no known biological effects of EMP. The ionized air also disrupts radio traffic that would normally bounce off the ionosphere.

One can shield electronics by wrapping them completely in conductive mesh, or any other form of Faraday cage. Of course radios cannot operate when shielded, because broadcast radio waves can't reach them.

Ionizing radiation

About 5% of the energy released in a nuclear air burst is in the form of ionizing radiation: neutrons, gamma rays, alpha particles, and electrons moving at incredible speeds, but with different speeds that can be still far away from the speed of light (beta particles). The neutrons result almost exclusively from the fission and fusion reactions, while the initial gamma radiation includes that arising from these reactions as well as that resulting from the decay of short-lived fission products.

The intensity of initial nuclear radiation decreases rapidly with distance from the point of burst because the radiation spreads over a larger area as it travels away from the explosion. It is also reduced by atmospheric absorption and scattering.

The character of the radiation received at a given location also varies with distance from the explosion. Near the point of the explosion, the neutron intensity is greater than the gamma intensity, but with increasing distance the neutron-gamma ratio decreases. Ultimately, the neutron component of initial radiation becomes negligible in comparison with the gamma component. The range for significant levels of initial radiation does not increase markedly with weapon yield and, as a result, the initial radiation becomes less of a hazard with increasing yield. With larger weapons, above fifty kt (200 TJ), blast and thermal effects are so much greater in importance that prompt radiation effects can be ignored.

The neutron radiation serves to transmute the surrounding matter, often rendering it radioactive. When added to the dust of radioactive material released by the bomb itself, a large amount of radioactive material is released into the environment. This form of radioactive contamination is known as nuclear fallout and poses the primary risk of exposure to ionizing radiation for a large nuclear weapon.

Earthquake

The pressure wave from an underground explosion will propagate through the ground and cause a minor earthquake. Theory suggests that a nuclear explosion could trigger fault rupture and cause a major quake at distances within a few tens of kilometers from the shot point.

Summary of the effects

The following table summarizes the most important effects of nuclear explosions under certain conditions.

|

Effects |

Explosive yield / Height of Burst |

||||

|

1 kT / 200 m |

20 kT / 540 m |

1 MT / 2.0 km |

20 MT / 5.4 km |

||

|

Blast—effective ground range GR / km |

|||||

|

Urban areas almost completely levelled (20 PSI) |

0.2 |

0.6 |

2.4 |

6.4 |

|

|

Destruction of most civilian buildings (5 PSI) |

0.6 |

1.7 |

6.2 |

17 |

|

|

Moderate damage to civilian buildings (1 PSI) |

1.7 |

4.7 |

17 |

47 |

|

|

Railway cars thrown from tracks and crushed (0.63 kg/cm2) |

n/a |

1.0 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

Thermal radiation—effective ground range GR / km |

|||||

|

Conflagration |

0.5 |

2.0 |

10 |

30 |

|

|

Third degree burns |

0.6 |

2.5 |

12 |

38 |

|

|

Second degree burns |

0.8 |

3.2 |

15 |

44 |

|

|

First degree burns |

1.1 |

4.2 |

19 |

53 |

|

|

Effects of instant nuclear radiation—effective slant range1 SR / km |

|||||

|

Lethal2 total dose (neutrons and gamma rays) |

0.8 |

1.4 |

2.3 |

4.7 |

|

|

Total dose for acute radiation syndrome2 |

1.2 |

1.8 |

2.9 |

5.4 |

|

1) For the direct radiation effects the slant range instead of the ground range is shown here, because some effects are not given even at ground zero for some burst heights. If the effect occurs at ground zero the ground range can simply be derived from slant range and burst altitude (Pythagorean theorem).

2) "Acute radiation syndrome" corresponds here to a total dose of one gray, "lethal" to ten grays. Note that this is only a rough estimate since biological conditions are neglected here.

Other phenomena

As the fireball rises through still air, it takes on the flow pattern of a vortex ring with incandescent material in the vortex core as seen in certain photographs. At the explosion of nuclear bombs sometimes lightning discharges occur. Not related to the explosion itself, often there are smoke trails seen in photographs of nuclear explosions. These are formed from rockets emitting smoke launched before detonation. The smoke trails are used to determine the position of the shockwave, which is invisible, in the milliseconds after detonation through the refraction of light, which causes an optical break in the smoke trails as the shockwave passes. A fizzle occurs if the nuclear chain reaction is not sustained long enough to cause an explosion, or if the explosion is of much less energy than expected. This can happen if, for example, the yield of the fissile material used is too low, the compression explosives around fissile material misfire or the neutron initiator fails.