In this chapter we examined the role of net exports in the economy. We found that export and import demand are influenced by many different factors, the most important being domestic and foreign income levels, changes in relative prices, the exchange rate, and preferences and technology. An increase in net exports shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right; a reduction shifts it to the left.

In the foreign exchange market, the equilibrium exchange rate is determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves for a currency. Given the ease with which most currencies can be traded, we can assume this equilibrium is achieved, so that the quantity of a currency demanded equals the quantity supplied. An economy can experience current account surpluses or deficits. The balance on current account equals the negative of the balance on capital account. We saw that one reason for the current account deficit in the United States is the U.S. capital account surplus; the United States has attracted a great deal of foreign financial investment.

The chapter closed with an examination of floating and fixed exchange rate systems. Fixed exchange rate systems include commodity-based systems and fixed rates that are maintained through intervention. Exchange rate systems have moved from a gold standard, to a system of fixed rates with intervention, to a mixed set of arrangements of floating and fixed exchange rates.

The following analysis appeared in a newspaper editorial:

“If foreigners own our businesses and land, that’s one thing, but when they own billions in U.S. bonds, that’s another. We don’t care who owns the businesses, but our grandchildren will have to put up with a lower standard of living because of the interest payments sent overseas. Therefore, we must reduce our trade deficit.”

Critically analyze this editorial view. Are the basic premises correct? The conclusion?

For each of the following scenarios, determine whether the aggregate demand curve will shift. If so, in which direction will it shift and by how much?

Fill in the missing items in the table below. All figures are in U.S. billions of dollars.

| U.S. exports | U.S. imports | Domestic purchases of foreign assets | Rest-of-world purchases of U.S. assets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | 100 | 100 | 400 | |

| b. | 100 | 200 | 200 | |

| c. | 300 | 400 | 600 | |

| d. | 800 | 800 | 1,100 |

Suppose the market for a country’s currency is in equilibrium and that its exports equal $700 billion, its purchases of rest-of-world assets equal $1,000 billion, and foreign purchases of its assets equal $1,200 billion. Assuming it has no international transfer payments and that output is measured as GNP:

Suppose that the market for a country’s currency is in equilibrium and that its exports equal $400, its imports equal $500 billion, and rest-of-world purchases of the country’s assets equal $100. Assuming it has no international transfer payments and that output is measured as GNP:

The information below describes the trade-weighted exchange rate for the dollar (standardized at a value of 100) and net exports (in billions of dollars) for an eight-month period.

| Month | Trade-weighted exchange rate | Net exports |

|---|---|---|

| January | 100.5 | −9.8 |

| February | 99.9 | −11.6 |

| March | 100.5 | −13.5 |

| April | 100.3 | −14.0 |

| May | 99.6 | −15.6 |

| June | 100.9 | −14.2 |

| July | 101.4 | −14.9 |

| August | 101.8 | −16.7 |

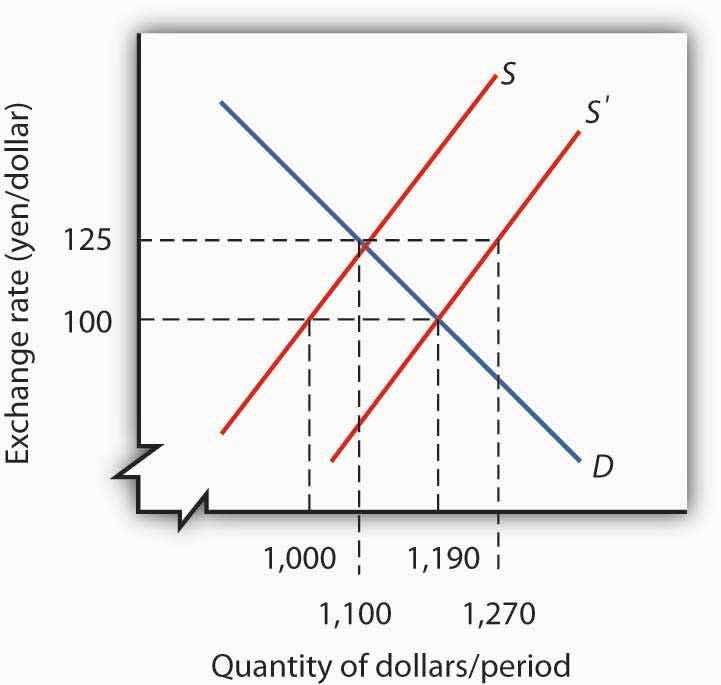

The graph below shows the foreign exchange market between the United States and Japan before and after an increase in the demand for Japanese goods by U.S. consumers.