Henry Clay and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 - Quiz

Choose your answer and write the correct one down. Then click HERE for the answers to this quiz.

NOTE: The transcript from the video is listed below the quiz for your reference.

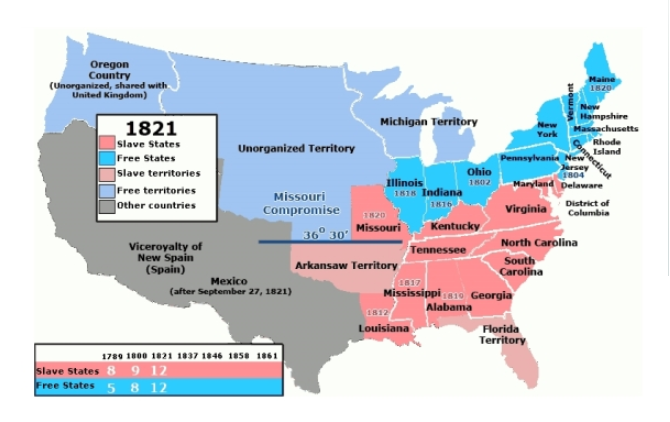

1. This map represents the nation after which event?

- The Kansas-Nebraska Act

- The Treaty of Ghent

- The Adams-Onis Treaty

- The expansion of the old southwest

- The Missouri Compromise

2. What was significant about 36°30'?

- It was the dividing line between slave and free states.

- It preserved peace until the Civil War.

- It created slave states out of the Old Southwest.

- It prevented any new states from being added for 15 years after Missouri.

- It was the southern boundary of the Louisiana Territory.

3. What was unusual about the admission of new states in the mid-1800s?

- There were none added.

- Congress could not vote on them.

- States were added in pairs.

- They were mostly Spanish-speaking.

- Only western states were added.

4. How did Henry Clay feel about Missouri?

- He wanted to add the state and allow the country to move on politically.

- He wanted a new slave state to increase his power in the Senate.

- He wanted to add the state so he could benefit from land prospecting there.

- He wanted a new free state to increase his power in the Senate.

- Hehoped to abolish slavery in the new state.

5. Which is a reason for the expansion of the Old Southwest before 1820?

- Thomas Jefferson wanted to improve the economy of the South.

- The Senate wanted to pull power away from New York.

- Henry Clay wanted to bring the transcontinental railroad through.

- More slave states were needed to balance the admission of free states.

- More land was needed for growing cotton.

In 1819, Missouri applied for statehood, threatening to tip the balance of senatorial power in favor of the slave states. Find out how Henry Clay resolved the matter for the next 30 years.

A Delicate Balance of Power

In the early part of the 19th century, the 'Old Southwest' region of the United States - that is, the area west of the Appalachian Mountains and south of the Ohio River - expanded to include what we now call the Deep South, and few Americans questioned that this was a good thing for the nation. There was more land for growing cotton, and access to the waterways was protected. In 1812, when James Madison was president, Louisiana became a state. To avoid confusion, the land that had formerly been called the Louisiana Territory was renamed the Missouri Territory. Next in office was James Monroe, under whom Mississippi, Illinois and Alabama were added to the Union without controversy. But then, in 1819, Missouri applied for statehood, and the so-called 'Era of Good Feelings' skidded to a halt.

In 1819, the nation contained 11 free and 11 slave states, creating an even balance in the U.S. Senate. Imagine being a U.S. senator at that time. How would you feel when Missouri - which seemed to be a little more northern than southern on the map - applied to become a slave state? Your feelings, of course, might depend on your opinion of slavery. They all knew that a new slave state would tip the balance of power in favor of the South. But the state had chosen slavery for itself, and that kind of autonomy was extremely important. Did Congress even have the authority to control this kind of decision? Of course, Northerners recognized that if a new slave state were added, the new senators would vote to expand slavery into all of the unorganized Western territory, and this was totally unacceptable to those who wished to see slavery at least contained, if not abolished. Southerners could see that if they lost this battle, the Northern senators would only admit more free territory until they had enough votes to amend the Constitution and outlaw slavery completely. Obviously, making a decision on this issue would have far-reaching consequences. To say the debates were heated is an understatement.

So why was slavery suddenly an issue when plenty of other Southern states had been added in recent years? It's never easy to pinpoint historical cause and effect, but there were a number of contributing factors. For one thing, during the two-party system of the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, there had been politicians from both North and South in both political parties, and the nation had pressing foreign issues until 1815, so you might say they just had other things to worry about earlier. Then, in 1817, New York passed a law that gradually emancipated all of its slaves, giving momentum to the abolition movement in the North and creating some worry in the South. All of these factors probably contributed, but don't forget the human factor. Are your most pressing political concerns the same ones you had a few years ago? Then, as now, the political concerns of the electorate were constantly shifting, even when old issues were unresolved. So, back to the original question: why was slavery all of a sudden the issue in 1819? It was just time.

The Missouri Compromise

Enter Henry Clay, a congressman from Kentucky. He proposed admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine (which had always been part of Massachusetts) as a free state. Besides resolving the immediate issue of maintaining balance in the Senate, he further proposed drawing a line across the map to determine the slave issue for states that were carved out of this territory. Anything above 36°30' would automatically be free; anything below 36°30' could choose slavery. The Missouri Compromise was accepted in 1820, and two years after applying, Missouri finally became a state in 1821.

The goal of the Missouri Compromise line was to keep slavery from becoming the deciding factor in westward expansion and allow the nation to move on politically. But many Americans correctly predicted that the line itself would become the problem. Thomas Jefferson was an old man and had long since retired from politics, but when he heard about the Missouri Compromise, he wrote a letter to a friend expressing his concerns:

'… this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed indeed for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.'

He was right, of course. The nation's funeral bells were hushed for 30 years, but not forever. The debate over Missouri had just exhausted everyone so much that no one even wanted to touch the subject again for 15 years. Beginning again in 1836, states were added in pairs, when Arkansas and Michigan joined the Union. This tension lasted for decades, and the Democratic-Republican Party began to fracture at the 36th parallel.

Lesson Summary

Let's review. For the first two decades of the 19th century, many new states joined the Union without issue. But bitter debate ensued when Missouri applied for statehood in 1819. The issue was partly the balance of power in the Senate and partly whether Congress had the right to override the will of the people in a state. Henry Clay proposed the Missouri Compromise: add Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state; then, draw a line at 36°30' as the slave border for all new states out of the territory. He hoped this would put an end to the slavery issue, but men like Thomas Jefferson correctly predicted that this would not truly solve the problem. After Missouri was added in 1821, no new states joined the Union for another 15 years, and after that, only in pairs. Politics became a sectional, rather than partisan, fight.