British Loyalists vs. American Patriots During the American Revolution - Quiz

Choose your answer and write the correct one down. Then click HERE for the answers to this quiz.

NOTE: The transcript from the video is listed below the quiz for your reference.

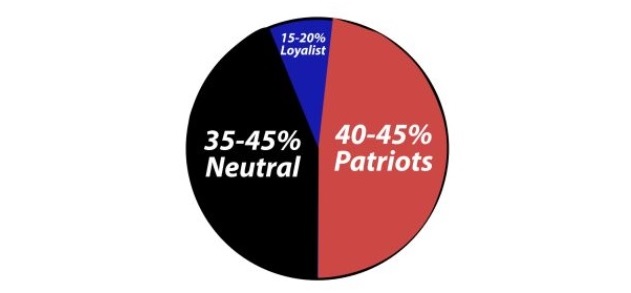

1. What does this chart reveal?

- There were about as many loyalists as patriots.

- The majority of colonists were loyalists.

- There were about as many patriots as neutrals.

- There were many more loyalists than patriots.

- The majority of colonists were neutral.

2. What was a common reason why Americans agreed to fight for the British?

- Slaves fought for the British in order to gain their freedom.

- Britain promised free land in the west to loyalist troops.

- Small merchants were offered lucrative business deals in exchange for service.

- The British army lured poor Americans because they paid better than the Continental army.

- Unhappy immigrants fought, hoping they'd be relocated back to England after the war.

3. Whose son fought on opposite sides from him in the Revolution?

- William Franklin

- George Washington

- Thomas Paine

- John Adams

- Benjamin Franklin

4. Who was most likely to be a patriot?

- A Native American

- A married woman

- A small merchant

- An African American

- A Pennsylvania colonist

5. Who was most likely to be a loyalist?

- A married woman

- An African American

- A small merchant

- A Pennsylvania colonist

- A Native American

In this lesson, learn about the difficult decisions faced by individuals as the American Revolution erupted. Would you have been a Loyalist or a Patriot? Are you sure about that?

A House Divided

Today, it's easy for Americans to say they would have been devoted Patriots from the start. After all, history is on their side. But if you had lived back then, you might have made a different decision. Colonists had a lot of conflicting loyalties and legitimate fears. One man's story might help you understand.

William had always done everything with his dad. As a child, he went on his business trips with him. They did experiments together. As a young man, the two were business partners. Then, at the ripe age of 32, William's father helped him get appointed as the royal governor of New Jersey. After all, his dad had taught him to be a good citizen, love the king, and respect authority. But his was a tough job in the days just before the revolution.

Like a lot of Americans, William didn't approve of the actions that the British government had taken against its own citizens. But he believed that the relationship between the king and colonies could and would be restored and that he was in a position of influence to help make that possible. Who knows? Maybe one day, he would even be the colonies' first Member of Parliament?

At first, his dad agreed with him and did everything he could to help solve the problems between Britain and the colonies. But eventually, his father was won completely to the Patriot cause and put pressure on William to quit his job and join them.

What should he have done? What would you have done? William decided that he should remain loyal to Great Britain. History shows that he chose poorly. When the Continental Congress overthrew the royal governments, William was sent to solitary confinement for two years, losing his hair, his teeth, his wife, and in a sense, his dad. His father didn't die, but after being sent to England in a prisoner exchange, William sent his father a letter. This is the response he received:

'Nothing has ever hurt me so much and affected me with such keen Sensations, as to find myself deserted in my old Age by my only Son; and not only deserted, but to find him taking up Arms against me, in a Cause, wherein my good Fame, Fortune and Life were all at Stake….Your Situation was such that few would have censured your remaining (neutral), tho' there are Natural Duties which precede political ones, and cannot be extinguish'd by them.'

Despite William's attempts, the two never reconciled. After the Revolution, his father disowned him, saying that if England had won, there wouldn't have been any inheritance for William, anyway.

William's father was Benjamin Franklin.

White Men Choose Sides

During the American Revolution, colonists like Benjamin Franklin who supported republicanism and eventually, independence, came to be known as Patriots. Historians estimate that about 40-45% of white men were patriots. Those men who chose to continue supporting the king, like William Franklin, were called Loyalists, or Tories. They made up about 15-20% of the white male population. The last 35-45% never publicly chose sides.

Just like political affiliations today, loyalists, patriots, and neutrals came from all social and economic classes, and many people took sides based not on principle but on who they thought was going to win or which side would profit them the most personally. But then, as now, there were demographic trends.

Poor farmers, craftsmen, and small merchants, influenced by the ideas of social equality expressed in works like Thomas Paine's Common Sense, were more likely to be Patriots. So were intellectuals with a strong belief in the Enlightenment. Religious converts of the Great Awakening made strong connections between their faith and a developing sense of nationalism. Loyalists tended to be older colonists, or those with strong ties to England, such as recent immigrants. Wealthy merchants and planters often had business interests with the empire, as did large farmers who profited by supplying the British army. Some opposed the violence they saw in groups like the Sons of Liberty and feared a government run by extremists.

Of course, many people never took a position. The largest group of neutral colonists was the Quakers, who are pacifists as a rule. They, and other religious pacifists, tried to carry on with life as usual, showing favoritism to none. But their willingness to do business with Britain led to resentment and mistreatment by the Patriots. Other neutral colonists definitely had an opinion about the war but were too scared to announce it publicly. Many colonists were confused - both sides seemed right and wrong. Some colonists, such as those way out on the frontier, weren't affected by all the politics and just didn't care.

Political Minorities Choose Sides

There was another large segment of the population that had definite opinions, but no political voice, notably women, African-Americans, and Native Americans. Married women generally chose the same side as their husbands. But a divided household (when a patriot woman's husband was a loyalist) was legal grounds for divorce. Native Americans who chose a side tended to be Loyalists, since the Proclamation Line had demonstrated Britain's willingness to respect their interests.

Free African-Americans frequently supported the Patriot cause. As citizens, they were inspired by Enlightenment ideals and the new language of liberty. They fought in the Revolution's earliest battles, but in 1775, Washington banned the enlistment or reenlistment of free blacks. This prompted the British to offer freedom to any slaves who fought for the king, encouraging slaves throughout the colonies to run away and join the Loyalists. In reaction, Washington lifted the ban on black soldiers from 1776 onward. However, freedom in exchange for military service was not Continental Army policy. That varied according to each state's militia. Maryland freed slaves who volunteered to fight, whereas in New England, a slave could only earn freedom if his owner sent the slave to serve in his place.

What Became of the Loyalists

Since Patriots subjected Loyalists, and even many neutrals, to the same public humiliation and violence with which they had handled British tax agents, many Loyalists who had the means moved to Canada or England early on. Loyalists who remained in the colonies during the war found their property vandalized, looted, and burned. As the war progressed, many relocated to British strongholds within America. In general, the cities (other than Philadelphia) had more of a British presence, while the countryside was the dominion of the Continental Army. The South leaned more towards the Loyalists while the Patriots were stronger in the North. In September 1776, loyalists flocked to New York after the British defeated George Washington and took control of Manhattan.

At the war's end, many remaining loyalists left the country by choice, including Native Americans. The British army evacuated thousands of freed slaves after their surrender, relocating them to Canada and England and even Africa. However, many others were abandoned in the South to re-enslavement, and a few were transported to plantations in the British West Indies as slaves.

Lesson Summary

At the start of the Revolution, Americans faced an important decision: would they side with the Patriots, or would they remain loyal to Great Britain? Both sides risked losing everything if their side lost, and at least a third of the colonists managed to avoid taking a public position. There were people from every social and economic class on both sides and in the middle, but there were demographic trends. Married women typically joined their husbands' side. Loyalists and neutrals often faced harassment or violence as a result of their position, and many Loyalists chose to relocate to British strongholds, such as New York. Thousands left the country after the war, including Native Americans and freed slaves.