Quantum

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In physics, a quantum (plural: quanta) is an indivisible entity of energy. A photon, for instance, being a unit of light, is a "light quantum." In combinations like "quantum mechanics", "quantum optics", etc., it distinguishes a more specialized field of study.

The word comes from the Latin "quantus," for "how much."

Behind this, one finds the fundamental notion that a physical property may be "quantized", referred to as "quantization". This means that the magnitude can take on only certain discrete numerical values, rather than any value, at least within a range. For example, the energy of an electron bound to an atom (at rest) is quantized. This accounts for the stability of atoms, and matter in general.

An entirely new conceptual framework was developed around this idea, during the first half of the 1900s. Usually referred to as quantum "mechanics", it is regarded by virtually every professional physicist as the most fundamental framework we have for understanding and describing nature, for the very practical reason that it works. It is "in the nature of things", not a more or less arbitrary human preference.

Contents

|

[edit] Development of quantum theory

Quantum theory, the branch of physics which is based on quantization, began in 1900 when Max Planck published his theory explaining the emission spectrum of black bodies. In that paper Planck used the Natural system of units he invented the previous year. The consequences of the differences between classical and quantum mechanics quickly became obvious. But it was not until 1926, by the work of Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, and others, that quantum mechanics became correctly formulated and understood mathematically. Despite tremendous experimental success, the philosophical interpretations of quantum theory are still widely debated.

Planck was reluctant to accept the new idea of quantization, as were many others. But, with no acceptable alternative, he continued to work with the idea, and found his efforts were well received. Eighteen years later, when he accepted the Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions, he called it "a few weeks of the most strenuous work" of his life. During those few weeks, he even had to discard much of his own theoretical work from the preceding years. Quantization turned out to be the only way to describe the new and detailed experiments which were just then being performed. He did this practically overnight, openly reporting his change of mind to his scientific colleagues, in the October, November, and December meetings of the German Physical Society, in Berlin, where the black body work was being intensely discussed. In this way, careful experimentalists (including Friedrich Paschen, O.R. Lummer, Ernst Pringsheim, Heinrich Rubens, and F. Kurlbaum), and a reluctant theorist, ushered in a momentous scientific revolution.

[edit] The quantum black-body radiation formula

When a body is heated, it emits radiant heat, a form of electromagnetic radiation in the infrared region of the EM spectrum. All of this was well understood at the time, and of considerable practical importance. When the body becomes red-hot, the red wavelength parts start to become visible. This had been studied over the previous years, as the instruments were being developed. However, most of the heat radiation remains infrared, until the body becomes as hot as the surface of the Sun (about 6000 °C, where most of the light is green in color). This was not achievable in the laboratory at that time. What is more, measuring specific infrared wavelengths was only then becoming feasible, due to newly developed experimental techniques. Until then, most of the electromagnetic spectrum was not measurable, and therefore blackbody emission had not been mapped out in detail.

The quantum black-body radiation formula, being the very first piece of quantum mechanics, appeared Sunday evening October 7, 1900, in a so-called back-of-the-envelope calculation by Planck. It was based on a report by Rubens (visiting with his wife) of the very latest experimental findings in the infrared. Later that evening, Planck sent the formula on a postcard, which Rubens received the following morning. A couple of days later, he informed Planck that it worked perfectly. At first, it was just a fit to the data; only later did it turn out to enforce quantization.

This second step was only possible due to a certain amount of luck (or skill, even though Planck himself called it "a fortuitous guess at an interpolation formula"). It was during the course of polishing the mathematics of his formula that Planck stumbled upon the beginnings of Quantum Theory. Briefly stated, he had two mathematical expressions:

- (i) from the previous work on the red parts of the spectrum, he had x;

- (ii) now, from the new infrared data, he got x².

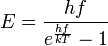

Combining these as x(a+x), he still has x, approximately, when x is much smaller than a ( the red end of the spectrum); but now also x² (again approximately) when x is much larger than a (in the infrared). The formula for the energy E, in a single mode of radiation at frequency f, and temperature T, can be written

This is (essentially) what is being compared with the experimental measurements. There are two parameters to determine from the data, written in the present form by the symbols used today: h is the new Planck's constant, and k is Boltzmann's constant. Both have now become fundamental in physics, but that was by no means the case at the time. The "elementary quantum of energy" is hf. But such a unit does not normally exist, and is not required for quantization.

[edit] The birthday of quantum mechanics

From the experiments, Planck deduced the numerical values of h and k. Thus he could report, in the German Physical Society meeting on December 14, 1900, where quantization (of energy) was revealed for the first time, values of the Avogadro-Loschmidt number, the number of real molecules in a mole, and the unit of electrical charge, which were more accurate than those known until then. This event has been referred to as "the birthday of quantum mechanics".