Arrhenius equation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Arrhenius equation is a simple, but remarkably accurate, formula for the temperature dependence of a chemical reaction rate, more correctly, of a rate coefficient, as this coefficient includes all magnitudes that affect reaction rate except for concentration.[1] The equation was first proposed by the Dutch chemist J. H. van 't Hoff in 1884; five years later, the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius provided a physical justification and interpretation for it. Nowadays it is best seen as an empirical relationship.[2]

Contents

|

[edit] Overview

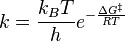

In short, the Arrhenius equation is an expression that shows the dependence of the rate constant k of chemical reactions on the temperature T (in Kelvin) and activation energy Ea, as shown below:.[3]

.

.

where A is the pre-exponential factor or simply the prefactor and R is the gas constant. The units of the pre-exponential factor are identical to those of the rate constant and will vary depending on the order of the reaction. If the reaction is first order it has the units s-1, and for that reason it is often called the frequency factor or attempt frequency of the reaction. When the activation energy is given in molecular units, instead of molar units, e.g. joules per molecule instead of joules per mol, the Boltzmann constant is used instead of the gas constant. It can be seen that either increasing the temperature or decreasing the activation energy (for example through the use of catalysts) will result in an increase in rate of reaction.

Given the small temperature range in which kinetic studies are carried, it is reasonable to approximate the activation energy as being independent of temperature. Similarly, under a wide range of practical conditions, the weak temperature dependence of the pre-exponential factor is negligible compared to the temperature dependence of the  factor; except in the case of "barrierless" diffusion-limited reactions, in which case the pre-exponential factor is dominant and is directly observable.

factor; except in the case of "barrierless" diffusion-limited reactions, in which case the pre-exponential factor is dominant and is directly observable.

Some authors define a modified Arrhenius equation,[4] that makes explicit the temperature dependence of the pre-exponential factor. If one allows arbitrary temperature dependence of the prefactor, the Arrhenius description becomes overcomplete, and the inverse problem (i.e. determining the prefactor and activation energy from experimental data) becomes singular. It has been pointed out that "it is not feasible to establish, on the basis of temperature studies of the rate constant, whether the predicted T½ dependence of the pre-exponential factor is observed experimentally".[2].. but if additional evidence is available, from theory and/or from experiment (such as density dependence), there is no obstacle to incisive tests of the Arrhenius law.

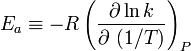

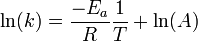

Taking the natural logarithm of the Arrhenius equation yields:

.

.

So, when a reaction has a rate constant which obeys the Arrhenius equation, a plot of ln(k) versus T -1 gives a straight line, whose slope and intercept can be used to determine Ea and A. This procedure has become so common in experimental chemical kinetics that practitioners have taken to using it to define the activation energy for a reaction. That is the activation energy is defined to be (-R) times the slope of a plot of ln(k) vs. (1/T):

[edit] Kinetic theories interpretation of Arrhenius equation

Arrhenius argued that in order for reactants to be transformed into products, they first needed to acquire a minimum amount of energy, called the activation energy Ea. At an absolute temperature T, the fraction of molecules that have a kinetic energy greater than Ea can be calculated from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of statistical mechanics, and turns out to be proportional to  . The concept of activation energy explains the exponential nature of the relationship, and in one way or another, it is present in all kinetic theories:

. The concept of activation energy explains the exponential nature of the relationship, and in one way or another, it is present in all kinetic theories:

[edit] Collision theory

One example comes from the "collision theory" of chemical reactions, developed by Max Trautz and William Lewis in the years 1916-18. In this theory, molecules are supposed to react if they collide with a relative kinetic energy along their line-of-centers that exceeds Ea This leads to an expression very similar to the Arrhenius equation, with the difference that the preexponential factor "A" is not constant but instead is proportional to the square root of temperature. This reflects the fact that the overall rate of all collisions, reactive or not, is proportional to the average molecular speed which in turn is proportional to T1/2. In practice, the square root temperature dependence of the pre-exponential factor is usually very slow compared to the exponential dependence associated with Ea, to the point that some think it can not be experimentally proven.

[edit] Transition state theory

Another Arrhenius-like expression appears in the "transition state theory" of chemical reactions, formulated by Wigner, Eyring, Polanyi and Evans in the 1930s. This takes various forms, but one of the most common is

where ΔG‡ is the Gibbs free energy of activation, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and h is Planck's constant.

At first sight this looks like an exponential multiplied by a factor that is linear in temperature. However, one must remember that free energy is itself a temperature dependent quantity. The free energy of activation includes an entropy term, which is multiplied by the absolute temperature, as well as an enthalpy term. Both of them depend on temperature, and when all of the details are worked out one ends up with an expression that again takes the form of an Arrhenius exponential multiplied by a slowly varying function of T. The precise form of the temperature dependence depends upon the reaction, and can be calculated using formulas from statistical mechanics involving the partition functions of the reactants and of the activated complex.