Wilson and Latin America

In principle, Wilson wanted to avoid the aggressive stance Theodore Roosevelt had taken toward Latin America. He negotiated a treaty with Colombia in which the U.S. apologized for its role in the Panama Revolution of 1903–1904. Wilson, however, did not shrink from intervention on behalf of American values, saying in 1913, "I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men." Between 1914 and 1918, the U.S. intervened in Latin America, particularly in Mexico, Haiti, Cuba, and Panama.

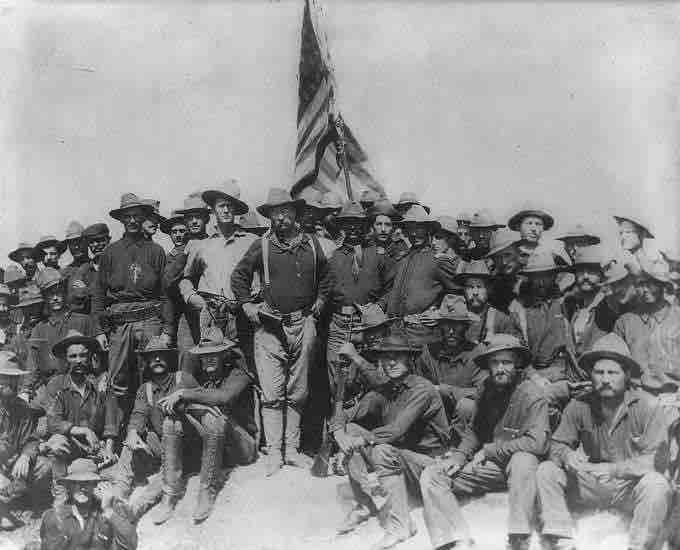

Roosevelt on San Juan Hill (1898)

President Wilson attempted a kinder foreign policy towards Latin America than his predecessor Theodore Roosevelt; however, in practice, their policies were very similar.

Economic concerns primarily drove these conflicts, known as "Banana Wars" due to the connections between interventions and American commercial interests in the region. The U.S. also advanced its political interests and sphere of influence, including control of the American-built Panama Canal, which was critically important to global trade and naval power.

Haiti and the Dominican Republic

American troops occupied Haiti between 1915 and 1934, forcing the Haitian legislature to choose a presidential candidate selected by Wilson.

In the Dominican Republic, Wilson ordered an American military occupation shortly after the resignation of President Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra in 1916. The U.S. military worked in concert with wealthy Dominican landowners to suppress the Gavilleros, a guerrilla force fighting the occupation that lasted until 1924 and was notorious for its brutality toward resisters.

Occupation of the Dominican Republic

Under Wilson's direction, U.S. forces occupied the Dominican Republic. (American Marines in the Dominican Republic in 1916 are pictured here).

Nicaragua and the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty

From 1912 to 1925, the United States had amicable relations with the Nicaraguan government due to friendly Conservative Party presidents such as Diego Manuel Chamorro. In exchange for political concessions, the U.S. provided the necessary military strength to ensure the Nicaraguan government internal stability. This led to the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty, signed on August 5, 1914, during the Taft administration, with formal ratification on June 19, 1916, during Wilson’s presidency.

The treaty was named after the principal negotiators, U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan and then-General Emiliano Chamorro representing the Nicaraguan government. Under the terms of the treaty, America acquired the rights to any canal built in Nicaragua in perpetuity, a renewable 99-year option to establish a naval base in the Gulf of Fonseca, and a renewable 99-year lease to the Great and Little Corn Islands in the Caribbean. Nicaragua subsequently received $3 million and ceded control of Nicaraguan foreign debt to the U.S. This arrangement lasted until the two countries abolished the treaty and its provisions on July 14, 1970.

The Mexican Revolution and U.S. Intervention

The United States intervened in Mexico throughout the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) to protect American national security and economic interests.

The Mexican Revolution was a major armed struggle that began in 1910 with an uprising led by Francisco I. Madero against longtime autocrat Porfirio Díaz and lasted until approximately 1920. Over time, the revolution changed from a revolt against the established order to a multi-sided civil war, with an end coming into sight only after the Mexican Constitution was drafted in 1917.

The relationship between Mexico and the United States at this time was turbulent. For economic and political reasons, the American government generally supported those who occupied Mexican seats of power, legitimately or not. Prior to Wilson's inauguration, the U.S. military settled for threating action against Mexico if the lives and property of Americans living in the country were endangered. President William Howard Taft amassed troops on the border, but did not allow them to intervene in the Mexican Revolution, a decision opposed by Congress.

There were two primary, linked motives for intervention. There was a pervasive anti-Hispanic ideology that justified U.S. military imposition of order on the Mexican “chaos.” This was fueled by pressure from American corporations who feared Mexican political restructuring would jeopardize their business interests.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, United States citizens and corporations owned about 27 percent of Mexican territory. By 1910, U.S. investment in Mexican land, railroads, mines, factories, and other ventures had further increased. The revolution hurt the Mexican economy and pushed Wilson to intervene in order to protect American interests.

Ypiranga Intervention and the Tampico Affair

The first time the U.S. sent troops into Mexico during the revolution was in response to the 1914 Ypiranga Incident. When United States intelligence agents discovered that the German merchant ship Ypiranga was carrying illegal arms to Mexican President Huerta, Wilson ordered troops to the port of Veracruz to prevent the ship from docking, leading to a skirmish with Huerta's troops. Yet the Ypiranga managed to dock at another port, infuriating Wilson.

Additionally, Mexican officials in the port of Tampico, Tamaulipas, arrested a group of U.S. sailors on April 9, 1914, including at least one taken from his ship, and thus from U.S. territory. After failed talks, the U.S. Navy bombarded Veracruz and occupied the port for seven months. Some argue that Wilson's true motivation was to overthrow Huerta, whom he refused to recognize as Mexico's leader. The Tampico Affair further destabilized his regime and encouraged the rebels. U.S. troops eventually left Mexican soil, but the incident worsened already tense relations.

Pancho Villa and Border Clashes

An increasing number of U.S.-Mexico border incidents early in 1916 culminated in an invasion of American territory on March 8, 1916, by Francisco “Pancho” Villa and his band of 500 to 1,000 men, who burned army barracks and robbed stores in Columbus, New Mexico. U.S. forces repulsed the attack, but 14 soldiers and ten civilians were killed, and Villa became the personification of mindless Mexican violence and banditry.

Pancho Villa Expedition

This political cartoon depicts American attitudes toward the expedition over the Mexican border in pursuit of Pancho Villa.

General Francisco Pancho Villa

Pancho Villa, second from the right, with his staff in 1913. Villa was an important leader during the Mexican Revolution.

In response, President Wilson sent forces commanded by General John J. Pershing into Mexico to capture Villa. Pershing's campaign consisted primarily of dozens of skirmishes with small bands of insurgents and Mexican Army units. Despite Pershing's efforts, Villa was deeply entrenched in the mountains of northern Mexico and knew the terrain too well to be captured. Pershing was forced to abandon the mission and return to the United States. Troops were withdrawn from Mexico by February 1917, but not before virtually the entire U.S. regular army became involved, with most of the National Guard federalized and concentrated on the border before the end of the affair.

John J. Pershing

General Pershing led the expedition into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa.

These events further damaged an already strained relationship and caused anti-American sentiment in Mexico to grow stronger, with minor clashes continuing along the border from 1917 to 1919. Although the Zimmermann Telegram affair of January 1917 did not lead to a direct U.S. intervention, it also exacerbated tensions between the US and Mexico. War would probably have been declared between the two nations if not for the critical situation in Europe.