Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

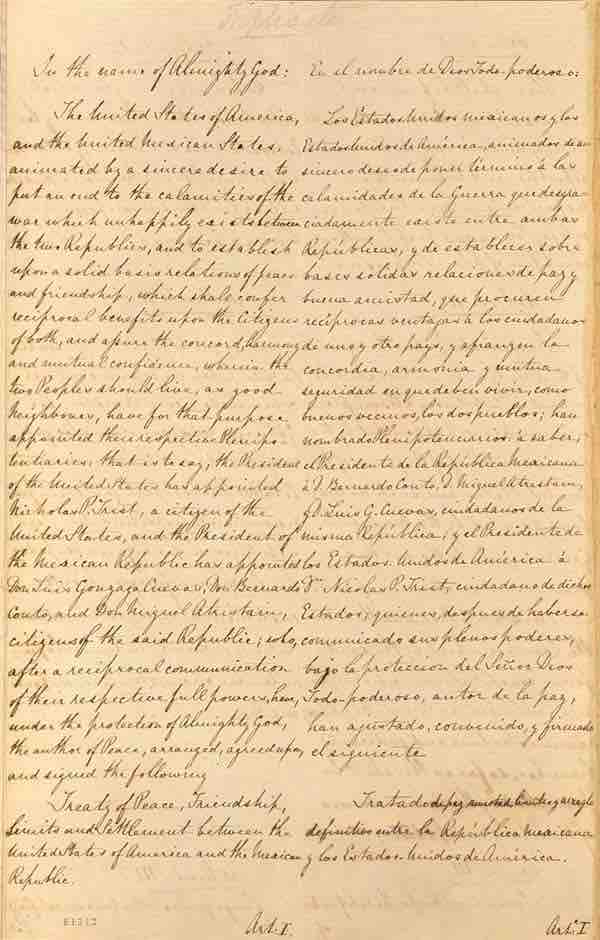

Outnumbered militarily, and with many of its large cities occupied, Mexico could not defend itself and was also faced with internal divisions. It had little choice but to make peace on any terms. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848, by U.S. diplomat Nicholas Trist and Mexican plenipotentiary representatives Luis G. Cuevas, Bernardo Couto, and Miguel Atristain.

The treaty ended the war and gave the United States undisputed control of Texas, established the U.S.–Mexican border as the Rio Grande River, and ceded to the United States the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. In return, Mexico received $18,250,000—less than half the amount the United States had attempted to offer for the land before the opening of hostilities—and the United States agreed to assume $3.25 million in debts that the Mexican government owed to U.S. citizens.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The first page of the handwritten Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican–American War.

Opposition to the Acquisition

The acquisition was a source of controversy, especially among U.S. politicians who had opposed the war from the outset. In the United States, increasingly divided by sectional rivalry, the war was a partisan issue and an essential element in the origins of the American Civil War. Most Whigs in the North and South opposed it, while most Democrats supported it. Southern Democrats, animated by a popular belief in manifest destiny, supported it in the hopes of adding slave-owning territory to the South and avoiding being outnumbered by the faster-growing North.

Northern antislavery elements feared the rise of a slave power; Whigs generally wanted to strengthen the economy with industrialization, not expand it with more land. John Quincy Adams in Massachusetts argued that the war with Mexico would add new slavery territory to the nation. Northern abolitionists attacked the war as an attempt by slave-owners to strengthen the grip of slavery and thus ensure their continued influence in the federal government. Democratic Congressman David Wilmot introduced the Wilmot Proviso, which aimed to prohibit slavery in new territory acquired from Mexico. Wilmot's proposal did not pass Congress, but it spurred further hostility between the factions.

Those who advocated for the war, in contrast, viewed the territories of New Mexico and California as only nominally Mexican possessions with very tenuous ties to Mexico. They saw the territories as actually unsettled (despite their large populations of American Indians), ungoverned, and unprotected frontier lands. The non-indigenous population there, where there was any at all, represented a substantial—in places even a majority—Anglo-American component. Moreover, the territories were feared to be under imminent threat of acquisition by the United States' rival, the British.

Impact of the War

Manifest Destiny

The acquired lands west of the Rio Grande are traditionally called the Mexican Cession in the United States, as opposed to the Texas Annexation 2 years earlier. Mexico never recognized the independence of Texas prior to the war, and did not cede its claim to territory north of the Rio Grande or Gila River until this treaty.

While the Mexican–American War marked a significant point for the nation as a growing military power, it also served as a milestone especially within the U.S. narrative of manifest destiny. The resultant territorial gains set in motion many of the defining trends in U.S. 19th-century history, particularly for the American West. In doing much to extend the nation from coast to coast, the Mexican–American War was one step in the massive westward migrations of Americans, which culminated in transcontinental railroads and the Indian wars later in the same century.

The Politics of Slavery

The 1848 treaty with Mexico was one of the most decisive events for the United States. in the first half of the 19th century. However, it did not bring the United States domestic peace. Instead, the acquisition of new territory revived and intensified the debate over the future of slavery in the western territories, widening the growing division between the North and South and leading to the creation of new single-issue parties. Westward expansion of the institution of slavery took an increasingly central and heated theme in national debates preceding the American Civil War. Increasingly, the South came to regard itself as under attack by radical northern abolitionists, and many northerners began to speak ominously of a southern drive to dominate U.S. politics for the purpose of protecting slaveholders’ human property. As tensions mounted and both sides hurled accusations, national unity frayed. Compromise became nearly impossible and antagonistic sectional rivalries replaced the idea of a unified, democratic republic.

The suggestion that slavery be barred from the Mexican Cession caused a split within the Democratic Party. The 1840s were a particularly active time in the creation and reorganization of political parties and constituencies, mainly because of discontent with the positions of the mainstream Whig and Democratic parties in regard to slavery and its extension into the territories. The first new party was the small and politically weak Liberty Party, founded in 1840. This was a single-issue party made up of abolitionists who fervently believed slavery was evil and should be ended, and that this was best accomplished by political means. In 1848, many northern Democrats united with anti-slavery Whigs and former members of the Liberty Party to create the Free-Soil Party. The party took as its slogan “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men,” and had one real goal—oppose extension of slavery into the territories.