Introduction: The Mexican-American Movement for Civil Rights

The African American bid for full citizenship was surely the most visible of the battles for civil rights taking place in the United States. However, other minority groups that had been legally discriminated against or otherwise denied access to economic and educational opportunities began to increase efforts to secure their rights in the 1960s. The Mexican American Movement was part of the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s seeking political empowerment and social inclusion for Mexican Americans.

Early Legal Victories

Like the African American movement, the Mexican American civil rights movement won its earliest victories in the federal courts. Prior to the movement of the 1960s and 70s, Mexican American civil rights activists had achieved several major legal victories. The 1947 Mendez v. Westminster Supreme Court ruling declared that segregating children of "Mexican and Latin descent" was unconstitutional, and the 1954 Hernandez v. Texas ruling declared that Mexican Americans and other historically subjugated groups in the United States were entitled to equal protection under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

In 1949 and 1950, the American G.I. Forum initiated local "pay your poll tax" drives to register Mexican American voters. Although they were unable to repeal the poll tax, their efforts did bring in new Hispanic voters who began to elect Latino representatives to the Texas House of Representatives and to Congress during the late 1950s and early 1960s. In California, a similar phenomenon took place. When Mexican-American Edward R. Roybal ran for a seat on the Los Angeles City Council, community activists established the Community Service Organization (CSO) which effectively registered 15,000 new voters in Latino neighborhoods. With this support, Roybal was able to win the 1949 election and become the first Mexican American since 1886 to win a seat on the Los Angeles City Council.

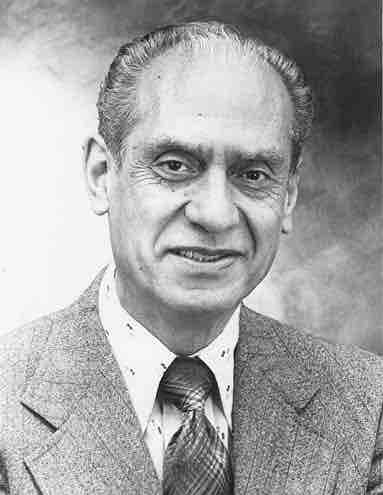

Edward R. Roybal

Roybal was the first Mexican American since 1886 to win a seat on the Los Angeles City Council

Chavez and Huerta

The highest-profile struggle of the Mexican American civil rights movement was the fight that Caesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta waged in the fields of California to organize migrant farm workers. In 1962, Chavez and Huerta founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). In 1965, when Filipino grape pickers led by Filipino American Larry Itliong went on strike to call attention to their plight, Chavez lent his support. Workers organized by the NFWA also went on strike, and the two organizations merged to form the United Farm Workers. When Chavez asked American consumers to boycott grapes, politically conscious people around the country heeded his call, and many unionized longshoremen refused to unload grape shipments. In 1966, Chavez led striking workers to the state capitol in Sacramento, further publicizing the cause. Martin Luther King, Jr. telegraphed words of encouragement to Chavez, whom he called a “brother.” The strike ended in 1970 when California farmers recognized the right of farm workers to unionize. However, the farm workers did not gain all they sought, and the larger struggle did not end.

The Chicano Movement

The equivalent of the Black Power movement among Mexican Americans was the Chicano Movement. The term "Chicano" was originally used as a derogatory label for the children of Mexican migrants; people on both sides of the border considered this new generation of Mexican Americans neither American nor Mexican. Proudly reclaiming and adopting a derogatory term as a symbol of self-determination and ethnic pride, Chicano activists demanded increased political power for Mexican Americans, education that recognized their cultural heritage, and the restoration of lands taken from them at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848.

One of the founding members of the Chicano Movement, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, launched the Crusade for Justice in Denver in 1965 to provide jobs, legal services, and healthcare for Mexican Americans. From this movement arose La Raza Unida, a political party that attracted many Mexican American college students. Elsewhere, Reies López Tijerina fought for years to reclaim lost and illegally expropriated ancestral lands in New Mexico; he was one of the co-sponsors of the Poor People’s March on Washington in 1967.

The Chicano Movement encompassed many issues, including restoration of land grants, farm workers' rights, improved education, voting and political rights, and an emerging awareness of collective history. It addressed negative ethnic stereotypes of Mexicans as presented in mass media and the American consciousness. Early activists adopted a historical account of the preceding 125 years, highlighting an obscured portion of Mexican-American history. These activists identified the failure of the United States government to live up to the promises it had made in Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. By their account, Mexican-Americans were a conquered people who needed to reclaim their birthright and cultural heritage as part of a new nation, which later became known as Aztlán.

When the movement faced practical challenges in the 1960s, most activists chose to focus on the immediate issues of unequal educational and employment opportunities, political disfranchisement, and police brutality. In the late 1960s, when the student movement was globally active, the Chicano movement brought about spontaneous actions such as the mass walkouts by high school students in Denver and East Los Angeles in 1968 and the Chicano Moratorium in Los Angeles in 1970. There were also many incidents of walkouts in the LA County high schools of El Monte, Alhambra, and Covina (particularly Northview), where students marched to fight for their rights. In 1978, similar walkouts took place in Houston to protest the discrepant academic quality for Latino students. There were also several student sit-ins in objection to the decreased funding of Chicano courses.

Young Chicanos for Community Action

In 1966, as part of the Annual Chicano Student Conference in Los Angeles County, a team of high school students discussed different issues affecting Mexican Americans in their barrios and schools. These high school students formed the Young Chicanos For Community Action (YCCA). In 1967, the YCCA decided to wear brown berets as a symbol of unity and resistance against discrimination. The Brown Berets took on a more militant and nationalistic ideology as the group focused on community organizing against police brutality and advocation for educational equality.

Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán

At a historic meeting at the University of California, Santa Barbara in April of 1969, the diverse student organizations came together under the new name Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MECHA). Student groups like these were initially concerned with education issues, but their activities evolved to include participation in political campaigns and protest against broader issues such as police brutality and the U.S. war in Southeast Asia.

Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional

Some women felt that the Chicano movement was too concerned with social issues that affected the Chicano community as a whole rather than problems that affected Chicana women specifically. This led Chicana women to form the Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional. In 1975, this group won the case of Madrigal v. Quilligan, obtaining a moratorium on the compulsory sterilization of women and adoption of bilingual consent forms. Prior to the case, many Latino women who did not understand English were being sterilized in the United States without proper consent.

Art of the Chicano Movement

A mural in Pilsen, Chicago for the Chicano Movement