Internal Contradictions

Although the Progressive Era was a period of broad reform movements and social progress, it was also characterized by loose, multiple, and contradictory goals that impeded the efforts of reformers and often pitted political leaders against one another, most drastically in the Republican Party.

For instance, national Progressive leaders such as Roosevelt argued for increased federal regulation to coordinate big business practices while others, like Wilson, promised to legislate for open competition. At the local, municipal, and state level, various Progressive reformers advocated for disparate goals that ranged as wide as prison reform, education, government reorganization, urban improvement, prohibition, female suffrage, birth control, improved working conditions, labor reform, and child labor reform. Although significant advancements were made in social justice and reform on a case by case basis, there was little local effort to coordinate reformers on a wide platform of issues. Furthermore, despite the Bull Moose Party's declaration of a Progressive Party Platform, the American public viewed it more as coalition of fervent Roosevelt supporters, rather than any comprehensive party platform that accounted for the range of Progressive concerns.

Furthermore, the Progressive Movement was also an exclusive phenomenon that was restricted to the white, Protestant, educated middle class. Racism often pervaded most progressive reform efforts, as evidenced by the suffrage movement. Specifically, as women campaigned for the vote, most progressives argued on behalf of female suffrage as a necessary reform to combat the influence of "corrupted" or "ignorant" black voters in the election booth. Civil Rights and Progressive Reforms were thus mostly exclusionary projects that had little real influence on each other in the early twentieth century.

Finally, many Progressive achievements were frustrated by the federal court system, which struck down laws regulating child labor, and by lack of resources and funds to fully implement social and political plans of reform. As a result, Progressives failed to fully redistribute political power from the hands of political lobbyists, machines, and organized interests.

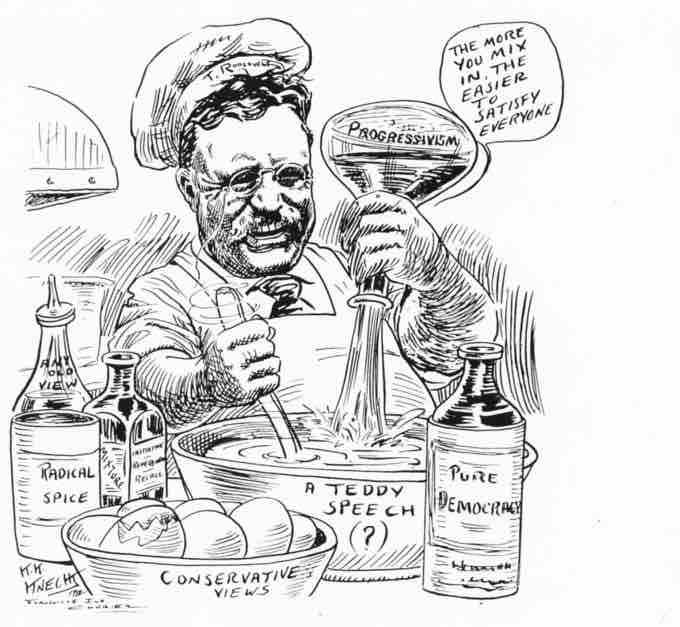

"The Chemist"

Roosevelt depicted as "concocting a heady brew in his speeches" in this 1912 political cartoon.

End of an Era

In addition to internal contradictions that limited the scope and success of progressives, the movement as a whole lost popular support around the time of World World I. There is much scholarly debate over the end of the Progressive Era.

The politics of the 1920s was unfriendly toward the labor unions and liberal crusaders against business, so many if not most historians who emphasize those themes mark the 1920s as the end of the Progressive Era. Urban cosmopolitan scholars recoiled at the moralism of prohibition and the intolerance of the nativists of the KKK, and denounced the era. However, as Arthur S. Link emphasized, the Progressives did not simply roll over and play dead. Link's argument for continuity through the twenties stimulated a historiography that found Progressivism to be a potent force. Palmer, pointing to leaders like George Norris, says, "It is worth noting that progressivism, whilst temporarily losing the political initiative, remained popular in many western states and made its presence felt in Washington during both the Harding and Coolidge presidencies." Gerster and Cords argue that, "Since progressivism was a 'spirit' or an 'enthusiasm' rather than an easily definable force with common goals, it seems more accurate to argue that it produced a climate for reform which lasted well into the 1920s, if not beyond."

Historians of women and of youth emphasize the strength of the Progressive impulse in the 1920s. Women consolidated their gains after the success of the suffrage movement, and moved into causes such as world peace,good government, maternal care (the Sheppard–Towner Act of 1921), and local support for education and public health. The work was not nearly as dramatic as the suffrage crusade, but women voted and operated quietly and effectively. Paul Fass, speaking of youth, says "Progressivism as an angle of vision, as an optimistic approach to social problems, was very much alive." International influences that sparked many reform ideas likewise continued into the 1920s, as American ideas of modernity began to influence Europe.

There is general agreement that that the Era was over by 1932, especially since a majority of the remaining Progressives opposed the New Deal.