Roosevelt and the Expansion of the Executive Branch

Perhaps one of the most remarkable characteristics of Theodore Roosevelt's presidency was his conviction that the president, by virtue of his election by the nation, was the representative figure of the American people, as opposed to Congress. Accordingly, Roosevelt believed that he could act in any manner that benefitted the needs of the nation, unless specifically and explicitly prohibited by the Constitution. In his own words, Roosevelt claimed, "I did not usurp power, but I did greatly broaden the use of executive power."

With his "big stick diplomacy" efforts in Latin America, as well as his efforts to expand the regulatory power of the federal government in domestic matters, Roosevelt set a new precedent for his twentieth-century political successors. Some of Roosevelt's most noteworthy legislative achievements—such as the Pure Food and Drug Act, the Hepburn Act, the Elkins Act, and his conservation laws—embody this concept of the executive branch as an expansive source of regulatory powers for the "good" of the nation. As some scholars have considered, Roosevelt's domestic policies, taken together, paved the way for the 1930s New Deal legislation as well as for the modern regulatory state and centralized national authority with expansive political power.

Despite Roosevelt's widespread popularity, many contemporaries resented his policies as encroachments on state power and local authority and accused him of concentrating all real political authority in Washington and replacing municipal and state structures with bureaucratic commissions and departments. Roosevelt, on the other hand, as a Progressive, remained committed to a belief in political efficiency and elimination of unnecessary waste and structures. To that end, by concentrating power in the executive and broadening the scope of federal regulatory power, Roosevelt was arguably attempting to create a modernized, Progressive United States that functioned seamlessly and in the better interests of the nation as a whole, rather than for local political authorities and wealthy interests.

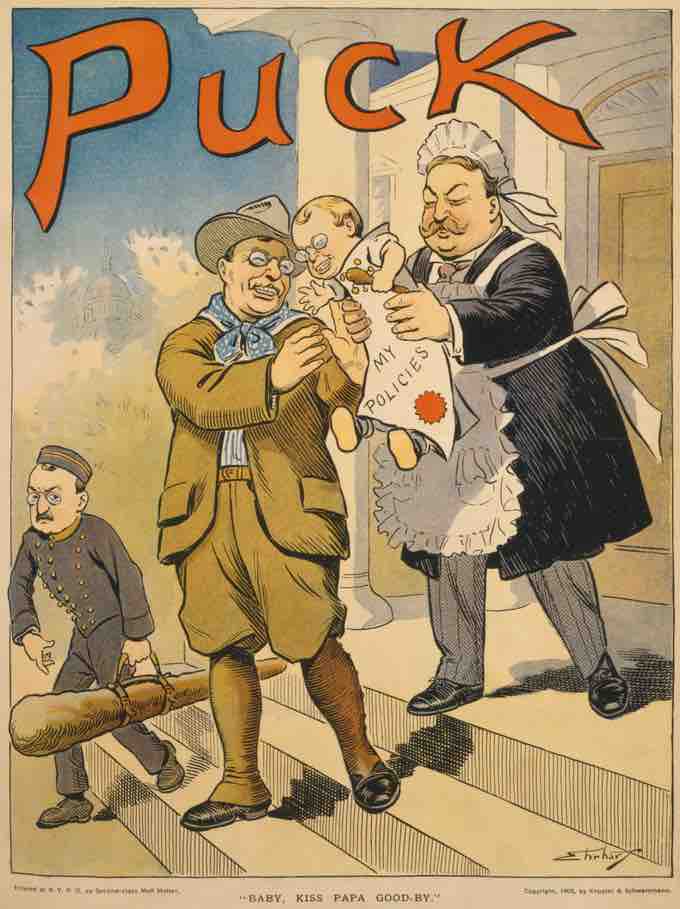

"Baby, Kiss Papa Good-By"

This political cartoon satirizes the expectation that Roosevelt would hand his policies over to the incoming president, William Howard Taft, his handpicked successor.