FINANCIAL CRISIS

Prior to the Great Depression, the gold standard was the foundation of the U.S. monetary system. Every U.S. dollar could be always exchanged for a fixed amount of gold, which meant that the supply of money could be increased only if the reserve of gold increased too. However, during World War I, many countries went off the gold standard to fund their war effort by printing paper money. In the aftermath of World War I, the international balance between gold reserves and paper money was thus dramatically shaken. While some European countries aimed to return to the gold standard, others were not able to do it and backed their currencies with the currencies that were backed with gold (like the U.S. dollar). That caused a very fragile international situation, in which national economies had little flexibility and governments made decisions depending on the relation between paper money and gold, despite the existing weaknesses of the post-WWI gold standard. Whether a country was on or off the gold standard, the connection of the most powerful national economies and currencies (most notably, U.S., Great Britain, and France) to the gold standard had impact on all. The outflow of gold in a country decreased the supply of money, which in turn triggered deflation (decrease in prices). As the Great Depression demonstrated, dramatic deflation resulting from the lower supply of money (and not inflation as many feared) was a massive threat to the economy.

When the U.S. stock market crashed in 1929 (some historians argue that the gold standard-based system is critical to the understanding of why the crash occurred) and panic ensued, many assumed that having cash or gold in hand would be safer than keeping their assets in banks. As Americans rushed to withdraw their deposits, many banks lost their reserves and were in turn forced to reduce their loans and deposits. With approximately only one third of banks belonging to the Federal Reserve System and thousands of unregulated commercial banks, the banking system was on the verge of collapse. Less money in circulation, higher borrowing costs, and lower wages entailed lower purchasing power of the consumer and lower profits for producers. Big companies, farm holders, and private households were not able to pay back their debts. Many of them went bankrupt. Production, both industrial and agricultural, halted as any form of investment was risky and falling prices made production unprofitable. With limited production, jobs disappeared. By the time Franklin Delano Roosevelt took over the office, the banking system practically did not function, unemployment reached a quarter of the labor force, and many Americans had lost whatever savings or investments they might have had.

While historians continue to debate the causes of the Great Depression, the gold-standard based international financial system of the end of the 1920s and the U.S. fragile, largely unregulated banking system, the stability of which depended on how stable the overall financial market was, are critical to the understanding of the most devastating economic crisis of the 20th century. Consequently, reforming finances was one of the very first targets of Roosevelt's New Deal.

THE BANKING REFORM

Less than two days after taking over the office, Roosevelt issued a proclamation that suspended all banking transactions. This national bank holiday, with banks closed and Americans having no access to their deposits, gave Congress enough time to propose banking reform legislation. On March 9, 1933, the Emergency Banking Act was introduced to and passed by Congress. This emergency law, initiated by the Hoover administration, retroactively approved of the bank holiday and presented a set of rules on how and which banks would be redeemed sufficiently stable to be reopened. Although designed as a temporary measure, banks began to reopen within days after the new law was passed and trust in the banking system was quickly restored. In June of the same year, more long-term solutions were presented in the Banking Act of 1933 (also known as the Glass-Steagall Act although this term is not precise and usually refers to the provisions of the Banking Act of 1933 that dealt with commercial bank). The most important provisions introduced by the 1933 Banking Act were:

- The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was established. All the FDIC insured banks were required to become or to apply to become members of the Federal Reserve System by July 1, 1934 (the deadline was later extended).

- Separation of commercial banking from investment banking. Institutions were given one year to decide whether they wanted to specialize in commercial or investment banking.

- Outlawing the payment of interest on checking accounts and placing ceilings on the amount of interest that could be paid on other deposits in order to decrease competition between commercial banks and discourage risky investment strategies.

- Regulation of speculations.

- Regulation of transactions between Federal Reserve member banks and their non-bank affiliates.

Some of the provisions of the 1933 Banking Act are still in effect.

MONETARY REFORM

In March and April of 1933, the Roosevelt administration also reformed the monetary system through executive orders and legislation. First, the government suspended the gold standard. The export of gold was banned, except under license from the Treasury. Anyone holding significant amounts of gold coinage was mandated to exchange it for U.S. dollars, at the current exchange rate. Furthermore, the Treasury no longer had to pay gold on demand for the dollar and gold was no longer considered valid legal tender for private and public debts. The dollar's value on foreign exchange markets no longer had price guaranteed in gold. With the passage of the Gold Reserve Act in 1934, the nominal price of gold was changed from $20.67 per troy ounce to $35 and most of the private possession of gold was outlawed. These reforms enabled the Federal Reserve to increase the amount of money in circulation to the level the economy needed. Markets immediately responded well to the reforms, with people acting on the hope that the decline in prices would finally end. In her work, What Ended the Great Depression?, economist Christina Romer argued that this policy raised industrial production by 25% until 1937 and by 50% until 1942.

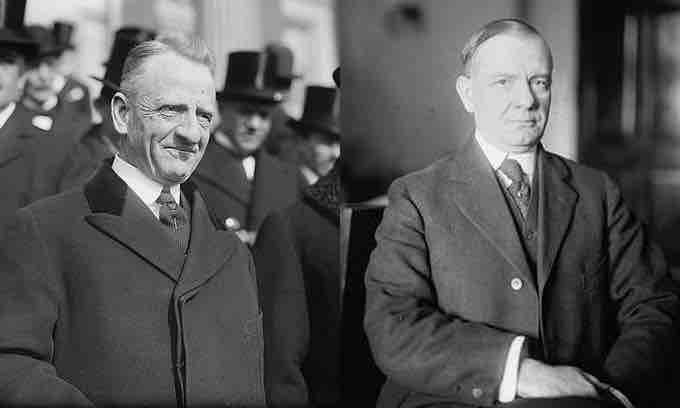

Senator Carter Glass of Virginia and Representative Henry Steagall of Alabama, the main force behind the 1933 Banking Act.

This picture shows the two congressional sponsors of the 1933 Banking Act, which introduced unprecedented reforms to the banking sector. Some of its provisions are still in effect.