THE ROOSEVELT RECESSION

Between the late spring of 1937 and early summer of 1938, the U.S. economy entered another period of economic downturn. Still in the midst of the Great Depression, the deepening of the economic crisis allowed the critics of the New Deal to strengthen their opposition to the reform, recovery, and relief programs introduced since 1933. Considering the downturn to be evidence that the New Deal did not work, the President's opponents referred to it as the Roosevelt Recession. While the severity of the recession paled in comparison to the severity of the most dramatic moments of the Great Depression, historians and economists note that the 1937-38 downturn was one of the most severe crises in U.S. history.

By 1936-37, the U.S. economy had improved significantly. Small inflation was recorded (and thus deflation stopped), GDP was on the rise, and employment, while still very high, fell from nearly 25% in 1933 to around 14% in 1937. In the months of the 1937-38 recession, the trends reserved rapidly. Unemployment jumped back to around 19%, prices fell again, and production, wages, and profits all substantially declined. Similarly to the witnesses of the recession, historians debate what caused such an extreme downturn in the midst of an already devastating economic crisis and their explanations correspond with different economic theories. Some blame Roosevelt's too early attempts to curb deficit by cutting spending after years of pouring money into costly New Deal programs. Others point to the changes in monetary policies introduced by the Federal Reserve that in 1936 doubled reserve requirements and tightened credit requirements (requiring banks to keep more reserves led to contraction in the money supply). Finally, an explanation favored by contemporary business leaders highlights the role of business regulations that in turn allegedly led to declining business profits and investments.

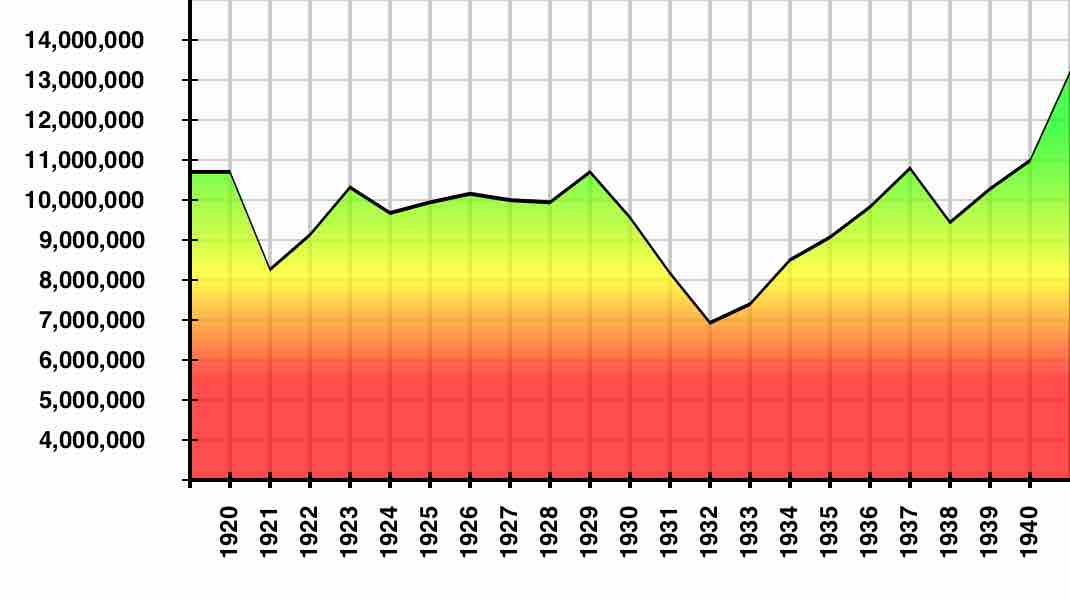

US Manufacturing Employment, 1920-40

Manufacturing employment in the United States from 1920 to 1940, with a drop between 1937 and 1938 during the Recession of 1937-38.

RESPONSE

As the causes of the recession were hotly debated, so were the government's response to the economic downturn. The Roosevelt administration applied two major strategies in order to reverse the crisis. First, Roosevelt gave up on the idea to balance the budget (curb deficit) and announced more New Deal programs that would increase spending. In the fall of 1937, the Housing Act (known also as the Wagner-Steagall Act) introduced government subsidies for local public housing agencies to improve living conditions for low-income families. In February 1938, Congress passed the second Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), which authorized crop loans, crop insurance against natural disasters, and large subsidies to farmers who cut back production. In April of the same year, the President sent a new large-scale spending bill to Congress, requesting $3.75 billion for various government projects. The bill passed with the overwhelming support of Democrats (and of some Republican). The second strategy that helped reverse the 1937-38 economic downturn were monetary reforms. The Federal Reserve decreased reserve requirements and the government's intervention in controlling gold reserves already in the country and coming into the country decreased. Furthermore, some earlier efforts of the Roosevelt administration coincided with the 1937-38 recession.

While more of a rhetorical than tangible reform response to the downturn, the anti-monopoly campaign also intensified as the big business once again could be blamed for another economic crisis. The campaign aimed to hurt big business that Roosevelt and his advisers saw as obstructing economic recovery. However, the Roosevelt administration failed to pass any major trust-busting legislation.

While the economy recovered relatively quickly, very high unemployment continued until the demands of World War II practically eliminated the problem.