Machine Politics

During the Gilded Age, politics were characterized by "political machines." A political machine is a organization in which an authoritative boss or small group commands the backing of a corps of supporters and businesses (usually campaign workers), who then receive rewards for their efforts. The machine's power is based on the ability of the workers to get out the vote for their candidates on election day.

Although these elements are common to most political parties and organizations, they are essential to political machines, which rely on hierarchy and rewards for political power, often enforced by a strong party whip structure. Machines sometimes have a political boss, and often rely on patronage, the spoils system, "behind-the-scenes" control, and longstanding political ties within the structure of a representative democracy. Machines typically are organized on a permanent basis instead of for a single election or event. The term may take on a pejorative roll when referring to corrupt political machines.

When a political machine won an election, it could remove all appointed officeholders, leading to a change in the makeup of the body as well as in the heads of government departments. At that time, many political offices also were elected. Many officials were elected to represent their ward, and not by the entire city. This system led to the election of people personally known to their communities, as opposed to people voters had heard of but didn't know.

The machines in the cities tended to be controlled by the Democratic Party, which allied with new immigrants by providing jobs, housing, and other benefits in exchange for votes. This was a challenge to the power of the old elites, whose families had lived in the United States for generations. Political machines routinely used fraud and bribery to further their ends. On the other hand, they also provided relief, security, and services to the crowds of newcomers who voted for them and kept them in power. By doing this, they were able to keep the people's loyalty, thus giving themselves more power.

The political machines gave lucrative government contracts and official positions to supporters. One of the most well-known machines was that of Tammany Hall in New York, long led by William Tweed, who was better known as "Boss Tweed." In addition to rewarding supporters, members of the Tammany Hall machine saw themselves as defending New York City from the residents of upstate New York and from the New York state government, who saw New York city as a ready source of funds to benefit upstate New York.

Theodore Roosevelt, before he became president in 1901, was deeply involved in New York City politics. In the following quote, he explains how the machine worked:

The organization of a party in our city is really much like that of an army. There is one great central boss, assisted by some trusted and able lieutenants; these communicate with the different district bosses, whom they alternately bully and assist. The district boss in turn has a number of half-subordinates, half-allies, under him; these latter choose the captains of the election districts, etc., and come into contact with the common healers.

Larger cities in the United States—Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Kansas City, New York City, Philadelphia, St. Louis, etc.—were accused of using political machines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Each city's machine lived under a hierarchical system with a "boss" who held the allegiance of local business leaders, elected officials and their appointees, and knew the proverbial buttons to push to get things done. Benefits and problems both resulted from the rule of political machines.

Before the 1930s, the Democratic Party in Chicago was divided along ethnic lines—the Irish, Polish, Italian, and other groups each controlled politics in their neighborhoods Under the leadership of Anton Cermak, the party consolidated its ethnic bases into one large organization. With the organization behind, Cermak was able to win election as mayor of Chicago in 1931, an office he held until his assassination in 1933. The modern era of politics was dominated by machine politics in many ways. The New Deal of the 1930s and the Great Society of the 1960s gave the Democratic Party access to new funds and programs for housing, slum clearance, urban renewal, and education, through which the party could dispense patronage and maintain control of the city. Machine politics persisted in Chicago after the decline of similar machines in other large American cities. During much of that time, the city administration found opposition mainly from a liberal "independent" faction of the Democratic Party. Many machines formed in cities to serve immigrants to the United States in the late nineteenth century who viewed machines as a vehicle for political enfranchisement. Machine staffers helped win elections by turning out large numbers of voters on election day. But even among the Irish, continued help for new immigrants declined over time. It was in the party machines' interests only to maintain a minimally winning amount of support. Once they were in the majority and could count on a win, there was less need to recruit new members, as this only meant a thinner spread of patronage rewards to be shared among the party members. As such, later-arriving immigrants, such as Jews, Italians, and other immigrants from southern and eastern Europe between the 1880s and 1910s, rarely saw any reward from the machine system. At the same time, most of political machines' staunchest opponents were members of the established class (nativist Protestants).

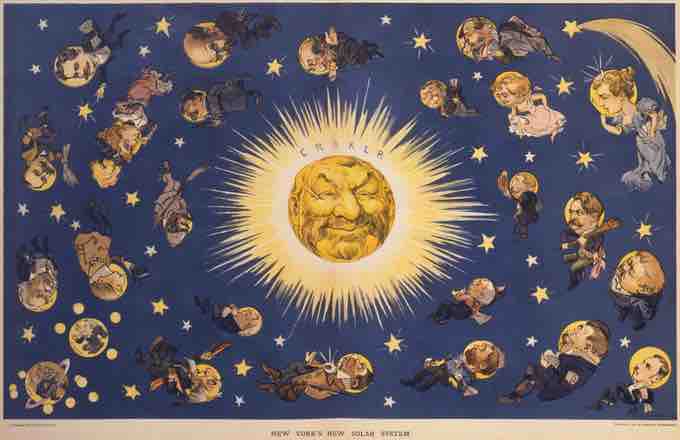

"New York's New Solar System"

This political cartoon from 1899 shows people from all walks of life revolving around a political boss, Richard "Boss" Croker.